A Fast Horse Never Brings Good News by Cary Fagan

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

The five stories in Cary Fagan’s A Fast Horse Never Brings Good News bring much good news in their pacing, good humour, and slides into magic realism, each story gaining in length as the book progresses. “The Big Story” pits petit récit against master narrative, as Fagan embeds stories within stories, stacking them like matryoshka dolls. The first-person narrator finds herself inside a restaurant with four other characters. “The idea of dining with strangers in a restaurant with a dress code – who could possibly find that appealing?” The reader soon finds the idea and strangers appealing, from the idea of a big story everyone’s been posting about to Orin and the narrator, who are complete strangers.

The narrator is the second-last person to arrive – “good timing, I thought,” part of good narrative timing throughout the careful pacing of Fagan’s fast horse. The restaurant’s wine-coloured carpet matches the wine being served, the narrator opens her mouth for conversation and food, and the main course of dry baked cod accompanies Eileen’s big story about almost drowning in the ocean. This décor continues when the narrator says “I’ll bite” in response to information about the big story, as Fagan matches eating and telling, recipe and récit, small bowls of salad and small park at the end of the story.

The narrator’s story is the most intriguing of all. When she was eight, she walked around her backyard greeting an apple tree, which talks back to her because a family inhabits the tree. This enchanted Eden bears fruit for the first time. When the others in the restaurant ask her about the meaning of her big story, she shrugs but says nothing. She establishes a mood of fictional afterglow between realism and magic realism. “There was a long pause” in the short story, as the narrator leaves the restaurant to go outside: “It was dark except for the circles cast by the street lights” – a cinematic aura after big and small stories that pool and ripple. The narrator pauses at a tree that has lost most of its leaves but has the right sort of branches for climbing. “But I was too old to climb and just put my hand on the trunk.” Life circles in the light between childhood and adulthood, and between embedded narratives and outer frame. “Doesn’t every story change something?” Fagan’s wry warmth answers this rhetorical question with yes, no, and the maybe of ambiguity.

Tree family morphs into talking pets in the second story, “Indivisible Property.” Fagan’s fable begins on a biblical note – “Before the animals began to talk came the breakup.” The breakup between Ryan and Jessica precipitates the conversations with their pets, Moochie the dog and Crook the cat. “It was 10 a.m., an unlikely time for ending a relationship.” This timely reminder launches the narrative about the duration of a relationship. Ryan and Jessica attend a play with their friends, part of the “small theatre scene” with large figures of Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelstam. Fagan seems to borrow a page from Woody Allen in his comic blend of high- and low-brow, shorting the long, and longing for the short. After the play Ryan reacts: “Talk about a lot of ideas to think about!” Their friend Nadia responds: “The way it pivoted between reality and those meta-fictional moments of pure theatricality?” With whispered ironies and tongue in cheek, Fagan’s dialogue pivots from thinking ideas to comic commentary.

On their own after the breakup, Ryan and Jessica begin anew. Ryan plans to furnish his basement apartment: “He couldn’t decide if the minimalist furniture reflected, or did not reflect, his taste.” Fagan’s minimalism gives rise to much humour when Moochie begins to talk to Ryan. Meanwhile, Crook addresses Jessica who tells the cat that she has “a weird sense of humour.” The narrator examines their situation: “Apparently the animal had a natural understanding of irony,” much like her author who indulges in feline felicity when Crook questions Jessica’s shared reading of Adrienne Rich with Ryan: “But did he really like those Adrienne Rich poems or was he just trying to please you because he’s such a nice guy?” Each in his or her own way, Crook and Moochie work to bring their human counterparts back together in a menage à quatre and dog.

When Ryan and Jessica meet again in the “neutral territory” of a café after Moochie asks, “Do you know if it’s possible to get un-neutered?”, comic realignment ensues. Jessica says, “I wasn’t trying to make some big thing,” as Ryan has “a small spill” of cappuccino on his jeans. They reconcile and find a new place to live together – “A fresh start demanded a fresh place.” As Jessica settles in with Crook, they engage in more comic dialogue: “I wish you would stop pacing … It’s driving me a little crazy.” The cat stops in the middle of the room: “Do you really have such weak territorial instincts? I need to make the place my own.” The line between human and feline characters is part of indivisible property of species. “I think you’re just nervous because Ryan is coming tomorrow. Admit it. You think he’s nicer than me.” The punchline in the episode: “Talk about projection.” The cat resumes her pacing. The pace of dialogue keeps pace with the action of projection, property, and place. There is good news in fiction’s pace, which puts human foibles and fables in their place. Cat and dog end up spooning in their masters’ bed and narratives, as their bemused eyes stare and wink in animal minimalism.

“Higher and Higher” consists of multiple segments scattered across New York City, where a book serves as protagonist in place of any single character. Once again, Fagan’s imagination is worthy of Woody Allen. The first sentence stretches his character’s name: Elizabeth Jaqueline Partnoy-Katz – a hyphenated teenager, part Portnoy, part feline delicatessen. The second sentence sketches and further stretches her: “She is fifteen but short for her age, in knee-torn jeans, vintage basketball jacket, Herschel backpack, and she is jumping Greenwich Avenue potholes on her Death’s Head skateboard.” In short, she’s an all-American character with a Canadian pack on her back. She enters a bookstore, Three Lives & Co., to find a book for her book report at school. Her teacher assigns Leo Tolstoy’s little book, The Forged Coupon, which is another model for “Higher and Higher” in the cumulative spread of minimalism. In the past she’s read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which was too complex, so instead she searches for “cute little paperback” beneath a sign that says Small Books, Big Stories.

She picks up a book with a flame on the cover and two flying birds, which serendipitously happens to be a copy of Fagan’s earlier novel, The Animals. Fagan’s fiction has an afterlife as well as an afterglow. She makes sure that the type isn’t minuscule, as Fagan continues to size matters up and allow his birds and book to fly across New York. Pace Norman Mailer’s Advertisements for Myself, Fagan advertises his book about miniature wooden models. Lizzie steals Fagan’s story and reads it while sipping her drink and typing her report. The narrator skateboards between genres from “Weird thing about essays” to “Funny thing about the book” – both adjectives qualifying Fagan’s fiction.

Bird-like, the book flies from episode to episode, character to character in a metafictional flight path of magic realism. It rests in the Minkoff Theatre where anaesthesiologist-in-training Ali Singh Ahani doubles as security guard and reads the book. Unlike Lizzie, Ali prefers the long, immersive novels of Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, and A.S. Byatt. He turns the pages of “this squib of a book” that challenges the master narratives with its postmodern ironies: “the back cover is bent and there is a small orange stain on the front and the pages smell slightly of fish. Perhaps, he thinks, this is more important than the story itself, that he join the anonymous chain of fellow readers.” With self-deprecating humour, the author teases readerly reception.

In the next episode another reader assesses the novel: “Unlike Stephen King, where you need to know what will happen next, this book is more like a series of moments that might or might not add up to something.” Fagan’s mathematics adds, subtracts, and multiplies floating signifiers as he clones and clowns himself. His miniature flirts with foreign syntax: “One dollar he can spare.” Theodore Glass offers tours of the city within this tour de force: “A metafictional tour, taking place in an imaginary village, visiting sites from the fiction itself!” Glass introduces himself as a flâneur, but the book he carries is the true flâneur, arcading through the sweep of New York City.

As the self-consuming book deteriorates to its separate pages, it ends up flying its pages in a dance of magic realism. “The leaves somersault in the air. Some rise, rush forward, and get caught in the low branches of trees.” Trope meets trope as the final character Clara Kahlo releases the fiction. She “lets the paper go so that it rises up and over the traffic and keeps going, higher and higher, until it disappears into the clouds.” This send-up, apostrophe, or apotheosis floats between foreground and the sublime.

Fagan’s tongue-in-cheek ventriloquism reappears in the first-person narrative of “Muswell Hill.” The nameless narrator of this British period piece refers to himself as “Mr. Hesitation,” for he hesitates on a number of fronts from cerebral contemplation to cloacal constipation to artistic expression in 1978. Most of the action takes place in a little row house in the London suburb of Muswell Hill, where a certain class consciousness comes into play in the various levels of rented rooms in the house. The narrator wishes to rise to the top floor from his inferior room a floor below. He has been promoted to assistant manager of the Bloomsbury branch of BestBrit ticket kiosks and knows his place: “I became second only to the manager, about whom I remain mum.” He also must remain mum when it comes to his landlady, Mrs. P., also known as “Mrs. Not Tonight Dear” – yet another form of hesitation. He plans to approach Mrs. P. once the room is vacant: “Then I shall literally move up in the world.” Upwardly mobile, he also moves laterally in his narration (“But I drift”) between his kiosk and his favourite instrument, a euphonium, an extension of his narrative voice. “Let me speak of the curvaceous sensuality of the euphonium. The kiss of the mouthpiece, the generously open horn.” Fagan’s instrument is funny, erotic, ironic, and warm; his music of the spheres spreads from Muswell Hill to other parts of the metropolis. Practicing at home, he is interrupted by Mrs. P. and her two sons who make indecent noises and slap their own rear ends, for the euphonium orchestrates its own brand of excremental vision and sound. Mrs. P. scolds her children but retains a “half-smile of amusement on her own horsey face” in her author’s horsing around. Mr. Hesitation hesitates to correct his narrative: “The last comment was cruel. I do not wish to lower myself to the level of these inadequately washed children. While it is true that Mrs. P. has a somewhat equine visage, she is not unattractive for a woman of thirty-five or so. If she is a horse, she is a handsome horse.” Her face brings good humour: Houyhnhnms ride beside irony and excremental vision, hesitating between fast pace and good news, cacophony and euphony.

Although the narrator prefers cinema to the theatre, he procures tickets for plays and is knowledgeable about London’s dramatic offerings. Of Tennessee Williams’s Vieux Carré he says: “The play had failed in New York due to a misguided production, and wasn’t it ironic that it took the superiority of English theatre to bring an American play to life.” Canadian imagination hesitates, mediates, and brings to life the British American scene. Irony mounts in the narrator’s background and adjustment to the English way of life. “Any free time I had was spent improving my speech, beating the foreigner out of me. Learning how to be English. One might say I performed my own Pygmalion, being both professor and student. Only I never fell in love with myself, that’s for certain.” Fagan improves his speech with layers of irony and self-deprecating pantomimic comedy à la Charlie Chaplin.

When he’s not playing the euphonium or selling theatre tickets, the narrator is busy writing a detective novel, which will be a short book “to bring both honour and innovation to the tradition.” Through various genres Fagan’s fiction combines tradition and innovation in what Sarah Selecky calls “post-ironic” warmth. In a comment on ventriloquism and mime, Mrs. P. addresses the narrator – “How you speak, sir! I almost feel as if I’m reading Trollope.” Mrs. P. has already rented out the top room to a young Canadian student studying drama who serves as a foil or alter ego for the narrator. The Canadian calls the room “picturesque,” for it is halfway to being sublime. Upset with her for renting out his desired room, the narrator thinks, “Mrs. P., you fishy-smelling bitch!” He hesitates after that exclamation: “On reflection, I feel some shame on having written that last sentence.” Like narrator and author, “Mrs. P. can be ironical … at times.” Ever the good sport, Mr. Hesitation puts the blame on himself: “I ought to be cursing myself.”

He practices his instrument at the Crouch End Playing Field and strives for proper embouchure, not just on the euphonium, but on verbalizing in general. After practice he returns home and engages in the soothing activity of ironing. With warm iron in one hand, and perma-press irony in the other, he smooths edges: “Perhaps the young people of today should drop their Buddhist meditation and psychoanalysis and iron their clothes instead.”

The young Canadian in his corduroy jacket is five foot six. “Glasses, a mop of curly hair, and a name … like that of a Jewish character in an American situation comedy,” who thinks that Woody Allen is a genius. “A great comic hero of our times.” Fagan’s anti-heroes deflate themselves: “Incidentally, my digestive problems have returned. They have given me frightful wind. I try to stay out of common spaces.” The euphonium transfers to the uncommon space of the woodwinds, as the narrator improves his glissando, “judging by my increased practice time and improved wind.” With Woody Allen’s clarinet putting wind in his sails, he improves. And in a self-reflexive, metafictional mode, “We are all heroes of our own story.” The anti-hero as schlemiel falls while the luftmensch levitates and suffers from stomach upsets: “the sad sound of my innards, much like the deflation of a balloon.”

The young Canadian’s play is Chekhov and Mandelbaum – cherry orchard and almond tree, Russian and Jewish. Narrator and Canadian attend a play together: A Day in Hollywood / A Night in the Ukraine. The two characters coalesce in a magical moment: “It was as if we had gone back in time to the days of vaudeville when those famous Jewish siblings the Marx Brothers used to ad-lib.” Fagan’s appetite for nostalgia encompasses an entire world; dramaturge and demiurge converge in a divine afflatus.

The euphonium in “Muswell Hill” glides into banjo, guitar, and fiddle in the final story, “The Musicianers,” as three different brothers replace the Marx Brothers. From the get-go, the story is a parody of the Western as Northern with animals playing their Faganesque roles alongside human beings. “The cow rooted in grass. She raised her kinked tail, tufted like a fraying rope, and shat. Something at the edge of her vision made her look up.” From excremental to peripheral vision, this sacrificial animal is all too human within this swish-buckler, semi-kinky tale or hide-and-seek quest. Three musicianer brothers exchange glances with the cow. Jimmy the short one plays guitar, Moses the tall one plays fiddle, and Douglas the middle one, banjo. In this carnivalesque farce the brothers “look like damn circus clowns.” Metafictional Moses, who always has the last word, accuses his brother of not finishing his sentences. The pile of cow dung they find turns out to be a border marker indicating that they have reached Canada after their long trek from North Carolina. Jimmy takes his little knife and slaughters the cow so that they may lessen their hunger.

In addition to his dusty bowler hat, cotton overalls, and fiddle, Moses carries matches in a brass cylinder hung around his neck along with a six-point silver star that had been left behind by his father, a dealer in religious goods. In this Saskatchewan barn-burner Moses fiddles with his Star of David and Yiddish syntax: “You maybe drink only bottled Perrier water from gay Paris?” Johansson, the Swedish owner of the cow soon appears and confronts the brothers with their crime. Shakespeare enters this comedy on the prairies when Johansson tells them that the name of the cow they killed is Cleopatra, his buffalo is Brutus, and his three daughters are Desdemona, Cordelia, and Juliet. To atone for their murder of Cleopatra, the brothers must pick up Brutus’s feces to be used as fertilizer – bushels in the bush garden.

Metafictional asides in the story add to the humour. Douglas says, “It’s like we’re characters in a story I’m making up in my head.” When the daughters serve the brothers bacon for breakfast, Moses declines. Douglas explains: “Our brother is a Hebrew. According to some book he read, Jews don’t partake of the cloven hoof.” This solecism is only half true because a kosher animal must have a cloven hoof and chew its cud. The pig does not chew its cud, but tongue-tied Moses adopts a baby pig he calls “Treyf,” meaning unkosher. In his bovine and porcine comedies, Fagan splits hairs and sides at outhouse and funhouse.

Tolstoy’s “highest spiritual capacity” enters the story alongside Shakespeare, the Marx Brothers, and Woody Allen as Fagan’s comedy passes between highbrow and lowbrow, faces and feces: “Someone passed a little wind. Everyone was careful not to register it on their faces.” Fefferman the saloon owner and Finbine the photographer round out this frontier farce, while a concertina and mandolin add to the rhythms of the musicianers’ polyphony on the prairies.

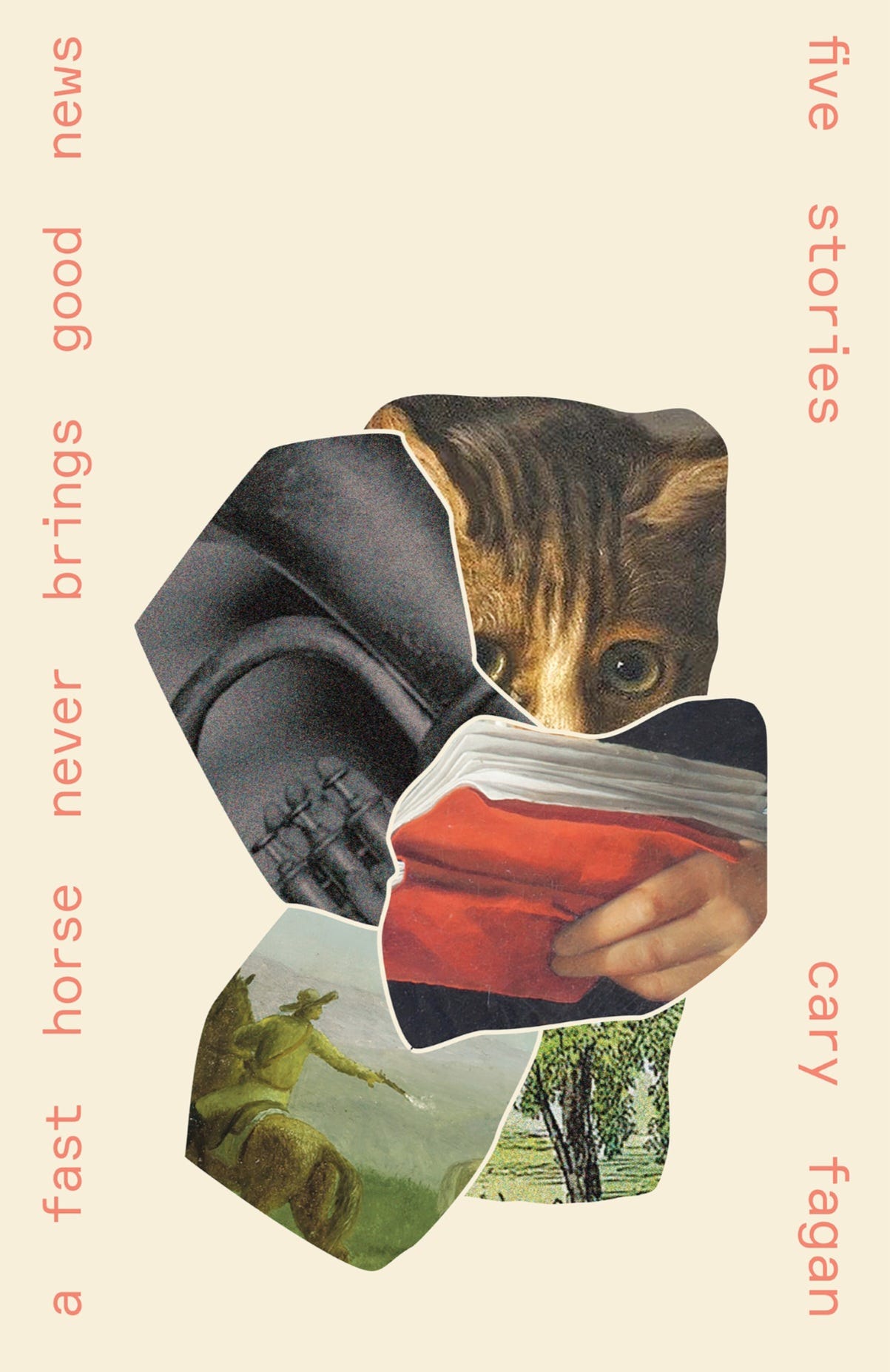

The collage on the book’s cover kaleidoscopes five overlapping images, each corresponding to a story. Animal eyes peek at the pages of a book held by fingers that reach toward a euphonium and a family tree, while a cowboy shoots the breeze, backfires, and delivers all the news that fits to print in the funhouse of fiction.

About the Author

CARY FAGAN is the author of eight novels and six short story collections. He has won many awards, including a Foreword Indies Silver Award for Humor, the Canadian Jewish Literary Award for Fiction, and the Toronto Book Award. He has also been nominated for various prizes, including the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction, the Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Award, and the Giller Prize. Fagan’s work has been translated into French, Italian, German, Dutch, Spanish, Catalan, Turkish, Russian, Polish, Chinese, Korean and Persian, and he is also a “beloved” (Quill & Quire) author of books for children. He lives in Toronto.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Book*hug Press

Publication Date: October 14, 2025

222 pages

ISBN 9781771669511