Every Nan in Newfoundland: A Review of Chores by Maggie Burton

A poetry review by Michael Greenstein

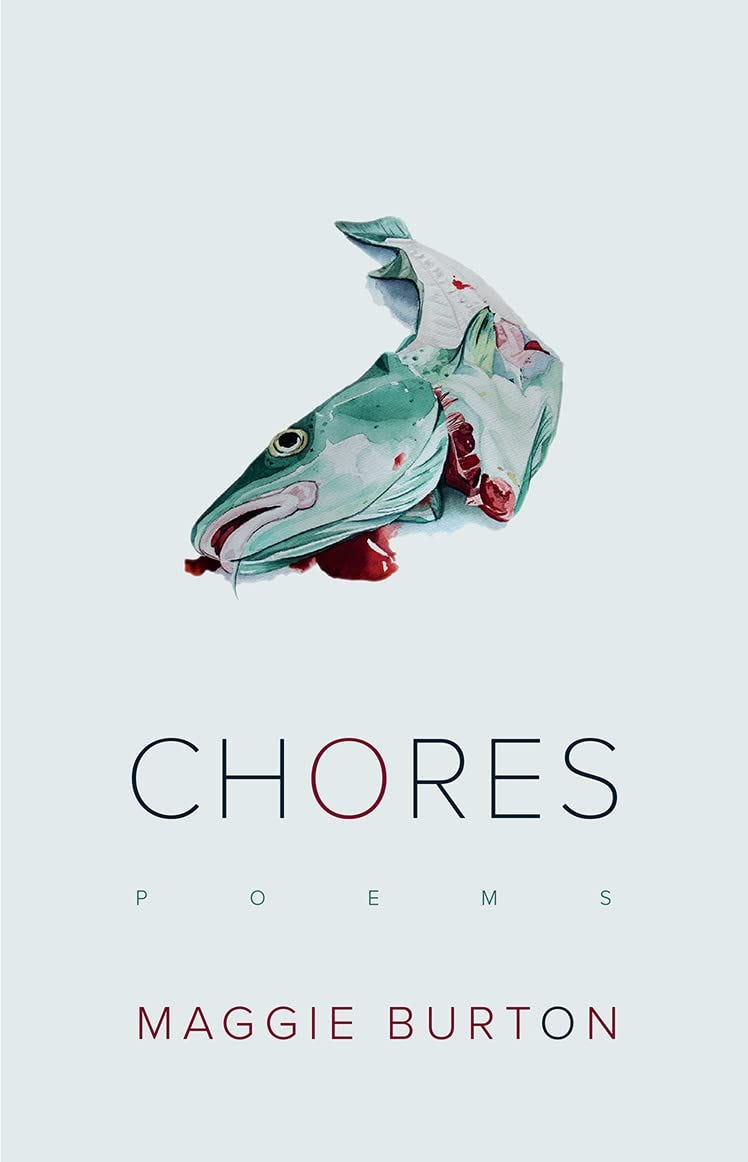

The precision of sound and vision in Maggie Burton’s debut collection of poems, Chores, is impressive and incisive, as she dissects the body politic across Newfoundland. The split fish on the cover swims and bleeds into the complexity of her first poem, “The Midwife”:

she caught babies in winter,

laid fish to dry in summer,

was eager to sop blood, guts

of anything pierced that needed

her.

This opening sentence swims through end rhymes of seasons to “eager” and “her” at various points in poetic and fishing lines. The twinned and twined roles of fishing and delivery in couplets are further enhanced by internal rhymes of “pierced” and “needed”; “caught,” “sop,” and “blood.”

The second sentence covers more couplets to develop the delivery of the first baby – “she fished him into her arms.” The midwife doesn’t see “the twin who slithered out // as if on a pelvic fin, hidden.” Again, Burton’s internal rhymes expose the dynamic hiddenness of twin delivery that leads outward

into the Old Port salt beef basket,

destined for the greedy harbour

to be released, returning

to something wet, smelling of home.

From home to harbour, the long e’s stretch outward, to be reeled in by t’s at the end of words in the double catch of sea and domesticity.

“The Midwife” waves between waters at home and abroad: “The bucket started howling on the walk / to the water.” The poem ends surprisingly by turning to the father who rubs “his baby’s eyes, sound broke from him, too // like a blow in the nautical chorus.” Sound breaks like the waters, and the nautical chorus includes the umbilical knot within the sound of Newfoundland.

This nautical chorus recurs near the end of the book in “I Watch You, Beheading,” where returning, smelling, howling, and waking from the first poem enter the participles of the later quatrains: “I hear them, singing, rehearsing, / lamenting, performing an ode to the freedom / of oceans somehow still resonating, settling / in my ears for me to live with.” Like Walt Whitman’s song to his American self, Burton’s domestic, democratic ode to Newfoundland is all-encompassing, embracing a microcosm of “voiceless vertebrates in the kitchen sink” and an oceanic macrocosm: “I see myself joining the nautical chorus, / all of us warbling together.” Nautical and anatomical, her aqueous chorus draws parallels between lines, lives, and loves: “I am struck by the quick parallel lines that appear / only to recede again under the skin of hands.” Her oceans resonate with a surge of anapestic breakwaters and beheadings against a vast backdrop of rock.

The initial nautical chorus leads to the seven sections of the titular poem, “Chores,” that amplify any singular activity beyond the simplicity of a monosyllable. Again, the opening couplet’s trochee captures family activity: “Pop snared rabbit, our early morning / catch. The woods were teeming.” Trapped r’s snag the rabbit, while “teeming” doubles the teams of plurals. Part “ii” shifts from Pop to Nan who “skinned the rabbit in the kitchen / sink.” Pop snares, Nan skins, and the drop of “sink” mirrors the drop of “stale” at the end of the first section. “Chores” establishes the kitchen sink as sacrificial altar where assorted rituals are enacted. The kitchen walls participate in these chores with fingerprints leaking from the old wood, “Soot black, sticky / as molasses.” The smudge of ancestry bears witness, while Nan cooks stew and homebrew, and dark streaks of nicotine drip from stucco walls.

Within these walls Pop watches John Wayne in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance with its bivalence of strength. The final section of this poem conflates the TV drama with domestic chores, while the space behind the labels of homebrew picks up the stickiness of the walls in the earlier sections. The shadow on the screen of the capper in the speaker’s hand becomes a loaded shotgun prepared for the next rabbit. Like Mary Pratt’s canvasses, Burton’s painterly woods and words teem with shelves of jelly and contours of colour.

Ordinary chores take on an aura of ritual in the tercets of “Radio Bingo:”

I sprawl on Nan’s bed, paint

my nails red, listen to VOWR’s

Hymns for the Quiet Hour

The poet paints opera in St. John’s radio station and becomes the wardrobe supervisor dressing the star who changes stations to the “Voice of the Common Man.” Burton’s postmodern melange mixes highbrow European culture with St. John’s common man. Nan becomes Every Nan and enters stage left, while “Don Giovanni hides in the living / room corner, double-timing // whiskey and homebrew.” Burton’s binoculars envision a double time frame from operatic stage to ordinary radio bingo with the announcer “crying into his double-double.” Dramatically the tercets double with Donna Elvira flying around the stage while Nan sits at the kitchen table and “stabs // the free spaces with her dabber.” Player’s cigarette smoke fills the free verse and settles into the next poem, “Bingo,” which is shaped like a card on the page.

“Bingo” ends with “smokes,” which in turn leads to “Smoke Made Mares’ Tails” and “I Rolled Smokes” – the smoke trope contributing to the oral domestic atmosphere, and spreading across the province with every Nan. An old Newfoundland rhyme serves as an epigraph to tall tales: “Mares’ tails and mackerel scales / make lofty ships to carry low sails.” Lofty and lowly sail through Burton’s verse. “For me, mares’ tails were smoke forming / over the table after Nan let me help.” Smoke begins in this homely setting before spreading to pervasive fog. “She lit a smoke, I felt the lighter click / inside my lungs. It was home.” Just as Nan represents every smoker, so her smoke extends to the overall fog across Newfoundland’s “mackerel sky.” From cigarette to fog over rock and sea, an ecosystem of smoke covers the vast province. The Rock is a breakwater carrying radio signals from across the Atlantic and looking westward to the rest of Canada in rhythms of home and away. Similarly, when the poet rolls smokes, she exhales to chorus the fog.

“Cleaning Out the Freezer” links domestic chores to a broader picture. As the poet cleans her freezer, she likens the appliance light to “what was seen / by men through fog on frozen floes.” Sealers hunting in the Narrows are compared to the narrow domestic space. A chorus of chores accumulates: “Cleaning Out the Fridge,” “Cleaning Out the Fish Tank,” “Checking the Mousetraps,” “Tweezing my Nipplebrows,” “Changing the Sheets,” “Hooking a Rug,” “Emptying the Vacuum,” “Cleaning Out the Sock Drawers,” “Doing the Dishes,” “Wiping Down the Counters.” She shapes many of these poems to imitate the chore’s rhythm and bring the outer world to drain in the kitchen sink. A downward motion dominates the later poems. “I put my hand in deep” to oceanic depths and mood changes. Syntax rearranges and estranges familiarity: “Dishwater a familiar warmth in this house, / alone.” She immerses herself beneath surfaces toward implication. Alternating d and p consonants submerge the “edge of the dinner plates, my nails pick / off the hardened pecks of flour, / rubbing patches on plate’s back / to elicit a response.” The dish’s anatomy responds in the second stanza as well, beginning with a crust of hard c’s: “Capelin clinging to unseasoned cast iron.” The downward motion continues to the bottom of the sink, while “unseasoned” meets season in the last line: “back to the beaten path, as the Evening Newshour / sounds the sundown-in-winter alarm.” Alliteration reverberates in the nautical chorus – a poetic collage of slap against sink.

“Wiping Down the Counters” undulates the Atlantic’s waves in a series of ups and downs from “cleanup” to “looking down” to tracing “lines on the linoleum up and down” to “wiping down” the counters. Nan takes you down to her place near the water. Countering this vertical decline is a horizontal expansion toward “the old harbour” until the poet, who feels a stirring deep inside, feels her body “become a breakwater --.” Her stirring words extend outward towards an oceanic identity. She is a breakwater embodying the Atlantic until she comes through and to her senses, absorbing waves. Her sensuality continues into “Peeling Pomegranates” and “Robin Soup,” the final poem in this collection, which spirals downward. As the speaker gulps down the last drops of soup, she repeats “Look at yourself / in the bottom of the bowl. Look / at yourself in the bottom of the bowl.” Doubling and twinning Burton’s intimacy and the coast’s immensity, these kitchen mirrors echo herself and the Rock’s fog and chorusing breakwaters.

About the Author

Originally from Brigus, Ktaqmkuk, Maggie Burton currently lives in St. John’s with her blended family, including four young children, a plethora of small animals, and her partner, Michael. Trained as a classical violinist, Maggie is a multi-disciplinary performer with a background in arts administration and music education. Maggie started writing poetry after having kids at the age of twenty. Currently, she dedicates her time to community-oriented work and writing. Her poems explore family, folklore, feminism, and sexuality.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

About the Book

Publisher : Breakwater Books (April 1 2023)

Language : English

Paperback : 80 pages

ISBN-10 : 1550819631

ISBN-13 : 978-1550819632