An Opening in the Vertical World by Roger Greenwald

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

New Directions

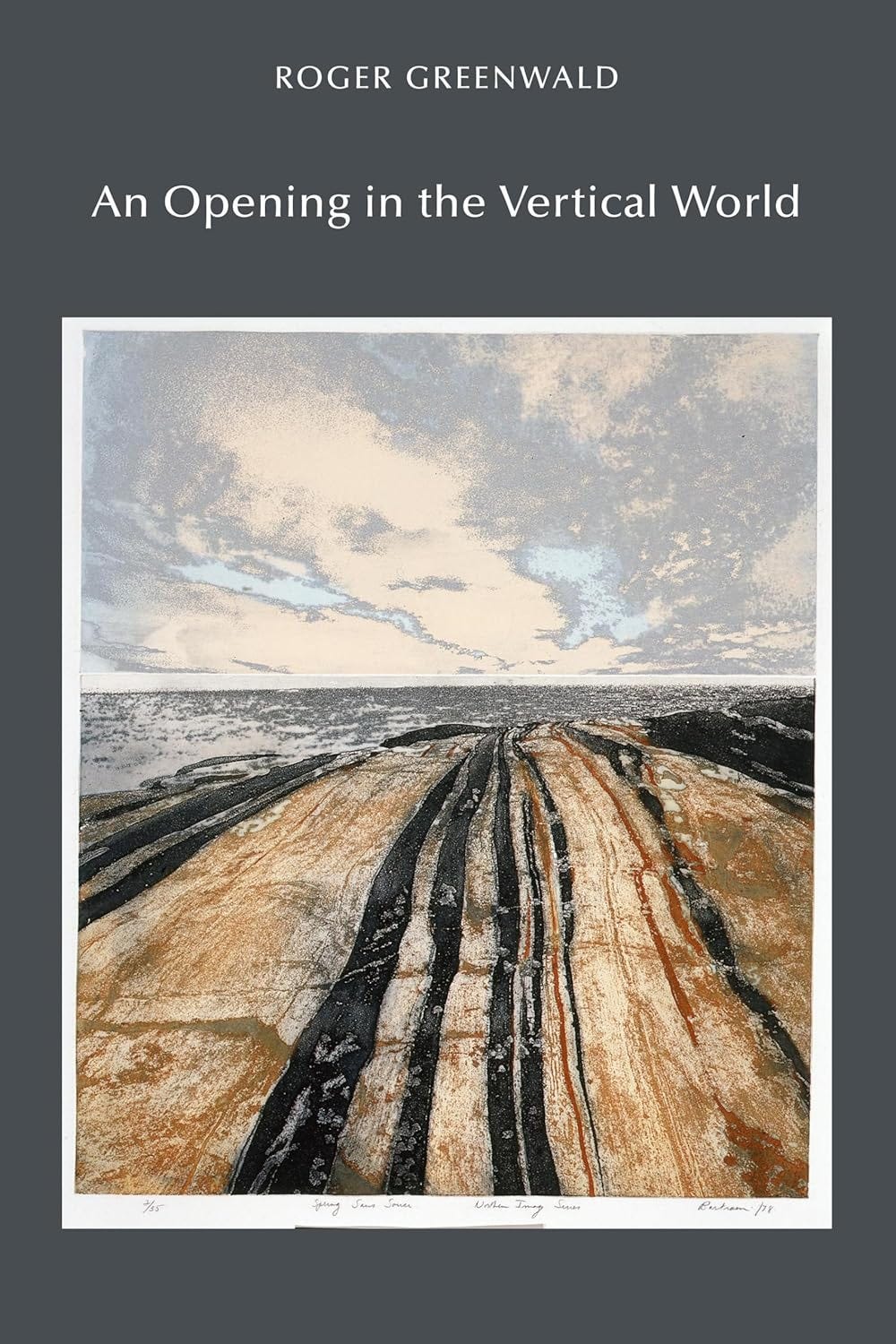

Ed Bartram’s etching, “Spring Sans Souci,” (1978) fittingly frames the cover of Roger Greenwald’s poetry collection, An Opening in the Vertical World. With its wooden grain texture, the rock in the foreground serves as a kind of runway for flights that confound horizontal and vertical vanishing points in the rhyming sky above Georgian Bay. This striated rock face reflects directions in poetic lines: against this stark landscape, the poems that follow position the aging poet along a receding horizon of wry reflection and translations of mood, music, and Nordic travel.

The opening poem, “In the Crowd,” spreads pentameters over two lines with the second line indented to add to its rhythmic motion. The initial negative places the poet within the crowd, but also apart from it, as he observes comings and goings. “Not to have one / person’s name to say.” This anonymity builds “To stand in the crowd before / the doors are opened.” After the initial “opening” sentence, a second long sentence works the crowd for the rest of the poem. Doors suggest the poet’s liminal position, which continues through the rest of the collection until the final poem, “Whisper Dance,” with its “dance to doors / that whisper back.” Whether in an airport lounge or on the dance floor, Greenwald listens to whispers and changes sides and directions in occasionally surreal choreography.

The poet begins in the crowd, at once inside and outside, a pronoun instead of a name: “you are carried with them / into the large hall” and into the music with a list of five hundred addresses, “the world outside, which is not / here with you.” Greenwald’s openings are over and under, outside and inside, above and below – horizontal and vertical axes mingling and interchanging. In the midst of all these comings and goings, a man with a mountain horn blows sounds that press against the poet’s identity, until a woman emerges: “she will / call the beginning / of something you belong to.” The muse summons beginnings, endings, and other boundaries; the crowd whispers, and is overheard.

After this introductory poem, the book’s first section, “Layover,” begins with “1969,” in which the poet traces the moving icon on his airplane’s screen. “As the red line pulled by the tiny airplane / arcs toward Montreal on the KLM monitor, / the towns of New York State appear to the south.” As Greenwald’s black lines pull the poem, he gives us a sense of direction over the lights of towns – “outposts of another kind.” Even as he lines up those towns, his vision reaches out to their “company among the nocturnal lakes.” The polarity between the minuscule and grandeur appears in the contrast between tiny airplane and “a large conversation.” After a musical accompaniment “on the loneliest of continents,” the line pulls and pushes to its conclusion: “But by now the tiny airplane has crossed Labrador, / pushed into the blue Atlantic; and the outside temperature / is minus fifty-nine,” not just to align with 1969, but to give us a sense of telescopic vastness and satisfying perspective between interior and the cosmic cold over outpost.

The flyover of “1969” turns to “Layover” in the next poem, which echoes “In the Crowd”: “Back to the crowd at Schipol, stretched out / on a bench, one arm through a loop / of my knapsack, one in the loophole / called dream.” Directions shifts from physical loop to dreamworld in the second stanza, as the poet reverts to his childhood: “In the dream on the bench / I am falling asleep, I am only five / in the yellow room at the end of the hall.” Stretched out on a bench, he recalls his grandfather “spreading out his paper”: “He turned the pages -- / reading right to left until the letters found their way / back to me.” The direction of the Hebrew letters finds the grandson who travels in the opposite direction across the page: “It wasn’t my intention to wander. I just / got detoured on my journey left to right. / I was heading east and got caught in a loop.” Greenwald’s looped journey is generational and oneiric, a Jewish wandering “waiting for something” in the layover’s loop and time’s detour.

Ancestral identity reappears in “Why I Am Not an Indian,” as directions shift and blur across continents. “I am not an Indian because / I am a Jew and don’t ask / what percentage, when I say Jew / I mean through and through.” After this witty rhyme, his thought gets completed with “though few who are Orthodox would say so.” His witty heterodoxy carries through his rhyme scheme: “It’s true no one knows / where we come from and my mother’s mother / with a tan could have looked Mongolian.” The negative quest continues in his ancestral trace: “could have come from people who millennia before / wandered eastward with their horses and eventually rode / into the cowboy films of my New York childhood.” These equestrians ride through a diaspora “where she, escaped from pogroms, / held a sugar cube between her teeth / to sweeten her lemony Russian tea.” After a lengthy wandering sentence, the poem reverts to negatives and a clipped shift in perspective: “But no, I am not an Indian. / So look again. Look in.” Greenwald’s anthropological gaze turns inward.

“In the Small of the Night” veers from special days that have “careened / out of orbit”: “Passovers wander off in the sands, / and the miracle of lights is an affair / for other people’s children.” Straying from these worn paths, the poet arrives at his calendar’s understanding: “Only the Day of Atonement retains / its genius, knowing you cannot exhaust / your supply of regrets.” Wit takes one further turn: “That is why / you hate it – and must atone / for that.” Greenwald listens to “the wailing tremolo of Hebrew prayers” and chooses a black skullcap for a moment of at-one-ment in the small of the night and the large of celebration.

Loss and loop of time and place pervade these poems. “Spring Flowers at Pompeii” begins with personification of season: “Spring is walking away from you.” This backward step extends “for at least / nineteen hundred and nineteen years.” Her “white flowers have just opened” – another opening in the vertical and horizontal world. The temporal world intrudes on the spatial in the pivotal “over”: “Over her shoulder you can glimpse her eyebrow / but she is not looking over her shoulder.” Greenwald’s optical exchanges interact with his directional pulls of vertical falls: “someone she was walking toward / when the heavens fell,” and the seasons age.

This section’s last poem, “Seeing Me,” enters the visual horizon and trompe l’oeil. “They say it’s hard to see yourself and that is true, / but often what they mean is it’s hard to know how others see you.” Mirrors turn in optical illusion of identity and self-scrutiny: “some friends express surprise / at humor in my poems. Or openness,” as he opens the door to his vertical world and loops the funny bone.

“Blue Vehicle” continues to explore the poet’s directional impulse defined through a negative: “The figures moving across the overpass / are not women.” The joining part of the blue vehicle moves “back and forth in different increments / like the dial of a combination lock.” The poet “will go out” through “his chosen door,” a lifetime’s leave taking: “symmetry’s beyond my view, fulfilled / only by a matching car / on adjacent tracks which may or may not appear / before I leave, almost close enough to touch.” Directions may be sensually charged amid intimations of mortality.

“Overcome” and “Run Over” further situate the poet. “Bergen, Port and Portal” contains the book’s title phrase with its visual appeal: “Look up, for this is an opening / in the vertical world.” The poet stretches to the sublime through his portal where “Nothing is horizontal.” Openings in the vertical world may be synaesthetic as “The Voice” begins with vision: “Power lines trace your line of sight, / high tension at the vanishing point.” Along lone lines perspective is voiced in sibilants, long i’s, and delayed alliteration of power point. Directions expand in up and down leading to clouds. Frame of view turns: “you are moving past the trees / and the trees past you.” In reciprocal voice and vision, the poet invokes Munch’s moonlit painting: “dark vibrating columns set off / by the white throat above the white dress.” (In an ekphrastic moment, these vibrating columns also apply to Bartram’s etching on the cover.) Munch’s throat gets transferred in the final stanza, which recapitulates “everything turning” and “Climbing spikes”:

At the top you are a spur

on the backbone of the mountain,

divide the beating city

from the random moor.

Everything’s alive, don’t worry.

Spur voices moor, backbone beating, mountain and moor in vocal directions.

“Wrong Directions” indicates the need for a poetic compass, and “Side Trips” hints at the poet’s lateral positioning where his house “is only an outpost.” His grandparents “had crossed two oceans in opposite directions.” From microcosmic outposts to larger dwellings, these journeys are crablike: “nothing but side trips from sideways trips, / and in the dusk a close-up view / of an oddly familiar claw.” Crustacean crawls in search of home amid diasporic detours. “Past” explores jazz and cinema where figures float “in a direction, there’s a future just offscreen.” The poem drifts through spatial-temporal axes “Past the middle of the forest” to “Past time is where you want to be,” while synaesthesia suffuses the atmosphere of a jazz club.

“Whisper Dance” ends on a Greek note of “Paraklausithyron” (a lament beside a door). Greenwald dances across these thresholds to the other side where all he needs “is to open, open, and open again.” In every direction he opens vertical and horizontal worlds from slanted diagonals of perception.

About the Author

ROGER GREENWALD attended The City College of New York and the Poetry Project workshop at St. Mark's Church In-the-Bowery, then completed graduate degrees at the University of Toronto. He has published three earlier books of poems: Connecting Flight, Slow Mountain Train, and The Half-Life.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Commonwealth Books, Black Widow

Publication date : Oct. 1 2024

Language : English

Print length : 76 pages

ISBN-13 : 979-8991139106