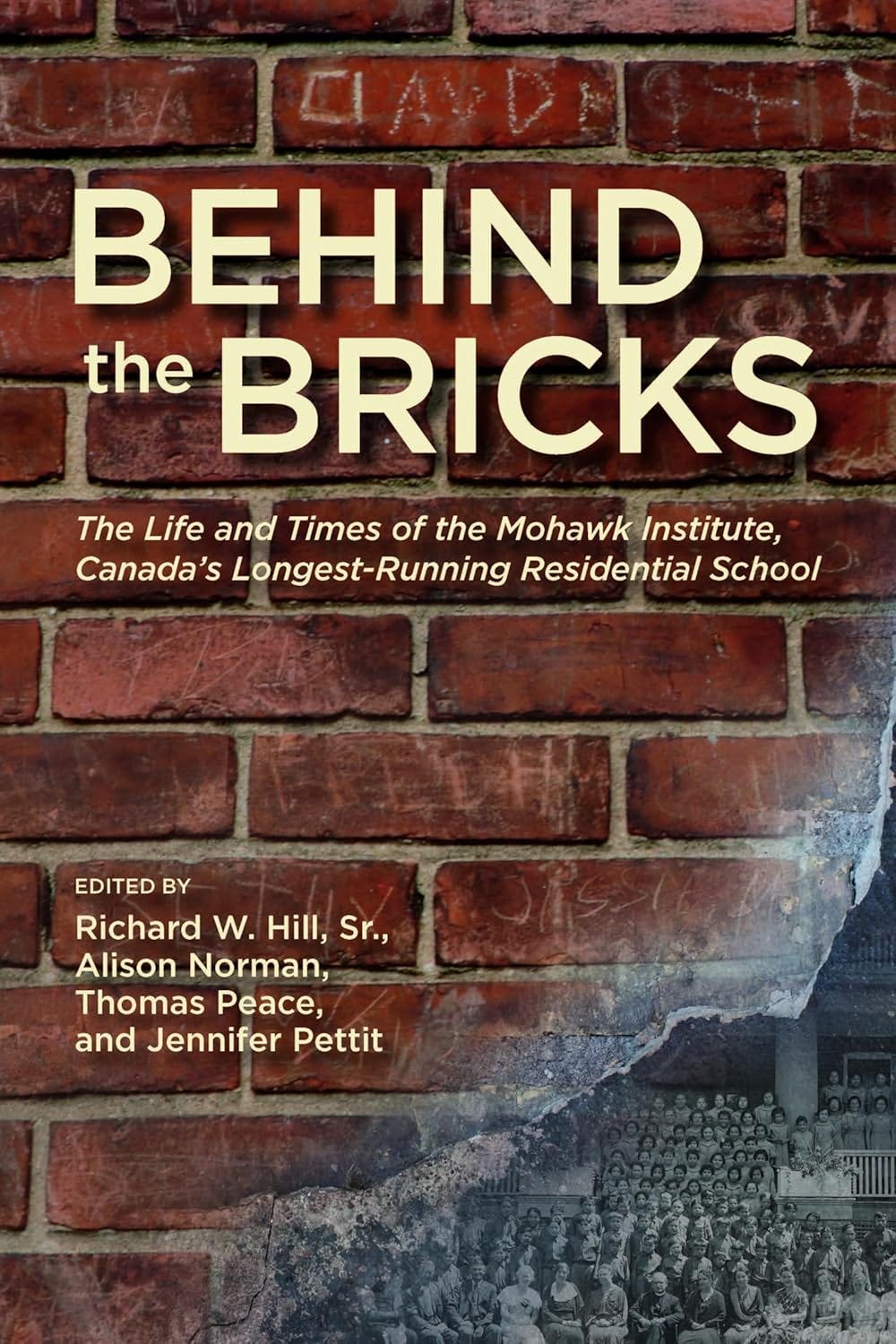

Behind the Bricks edited by Richard W. Hill Sr, Alison Norman, Thomas Peace, and Jennifer Pettit

The Life and Times of the Mohawk Institute, Canada's Longest-Running Residential School

Behind the Bricks is a comprehensive study of the life and times of the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario, one which not only details student experiences but grounds them in the overall historical, social, archaeological, architectural, and religious context, with each analysis reflecting the specific milieu and outcomes during different time periods. Drawing on Indigenous and settler scholarship, as well as a variety of research tools, it provides a well-rounded and thorough examination, not only of the Institute itself, but also its impact in comparison with other residential school models. As readers, we are urged not to observe only, but to take what we learn and “make concrete actions toward truth and reconciliation.” (7) The goal Is to produce or contribute to the truth, and as is pointed out, “Without this truth, there can be no reconciliation.” (9)

The study provides an insightful review of the goals of the institution, its purpose in the colonization process, and even the personal aspirations of key figures. All elements are scrupulously researched and documented; this perhaps makes the emotion of the overall presentation more intense. As the stories of the survivors are revealed, especially in the final chapters when story after story is shared, we have a context in which to receive these. After we have read of Indigenous aspirations for education, learned the colonial policy for Indigenous children, studied the profiles of staff, administrators, and other players, scrutinized the daily schedule, examined the blueprints with the sharp corners and many little rooms, our eyes become a little more open. The stories of the survivors touch us in a new way, and we realize anew that we can never truly know what these individuals know and carry in every moment.

I will not attempt to provide a succinct summary of this text, but I urge the reader to take the time for a thorough reading, for there are sections analyzing each formative aspect: the historical setting in terms of colonial policy and Indigenous expectations, the delivery of “curriculum” (which seems to view school work as a storm day activity, with an emphasis on labour), the structure and rationale of discipline and learning, the function of the Mohawk Institute in the matrix of the residential school system, the revelations of archaeology, the ways in which architecture reinforced the colonial view, the function, and failures of religion, and ultimately, the history told from behind the brick walls of the Mohawk Institute in the accounts of the survivors.

Each chapter is followed by pages of endnotes, documenting each revelation. Read these, too, and study the documents and photos included. Figure 15.1, Trauma by R. G. Miller, and 16.9, the “help me” brick, are particularly haunting, but every pair of eyes in every photo speaks to the reality of the trauma endured. There are many stories given—stories of intense pain, recollections of impressions, memories recalled, accounts of day-to-day life—all taking place in the context of a daily tragedy. There are appendices expanding the information of the study. The entire presentation forms a cohesive whole, and each aspect is important.

Some points are highlighted in this review, but these are by no means comprehensive. As an educator, I was drawn to the curriculum delivered. A very basic math and literacy program was provided, and delivery of this seemed weather dependent in the case of the boys, who otherwise were busy providing manual labour. It seemed even more negligible in delivery for the girls, who spent an inordinate amount of time on needle work and cleaning. It seems they were responsible for stitching all the clothes and bedding for the Institute, while the boys ran the farm. This brings us to nutrition, and for the time they spent cultivating crops and tending livestock, there was a remarkable lack of protein or produce in their menu, and an overwhelming emphasis on substandard porridge. One wonders where the income went, considering that unpaid labour was used, and that protein and produce was certainly going elsewhere.

The Indigenous community, it appears, had hopes of their children receiving education that would prepare them for life in the colonized world, to understand colonial methods of farming and to have the knowledge that would make them independent in that world. It seems the NEC (New England Company) and other concerned parties soon realized that this would mean competition for the settler community, and the “model industrial school” devolved to a manual labour status. Intelligence testing justified this rationale, for it revealed a “lower intelligence,” but how could testing of children traumatized by dislocation, tested in a new language in a culturally biased setting, malnourished and in fear of new or continued mistreatment, reflect an accurate assessment?

The conditions of the school are revealed in meticulous detail: the totally inadequate diet, the crowded conditions, the lack of sanitation, and the intensifying use of corporal punishment. The regulation strappings were not seen to be effective, and the situation deteriorated to arbitrary, often vicious beatings and confinement, which exceeded even the brutal standards in that historical period. Segregation of girls and boys was absolute; there was no affection or opportunity for affection. In terms of food, the book has an excellent section documenting not only nutritional value, but ceremonial value forming a vital part in the Indigenous experience of food. In no way were children receiving an educational experience.

When and if the children went home, their relationship with their home world was now broken. They had been subjected to three forms of trauma: lack of love, stripping away of cultural expression, and loss of family. It is noted that there was a high level of fighting and violence within the student population, and given the framework of their lives, we should not be surprised.

Children resisted by running away; there is a significant history of these “fugitive” absences. And there are many names scratched into the bricks—not the numbers they were assigned; they resisted by reclaiming their names. (The book also traces the plans for the Institute after its closure and discusses the role of such sites and their artifacts in the path of truth and reconciliation.) Some students did train as teachers, though, and an appendix provides a comprehensive list. One wonders about the adequacy of their training, given the conditions of the school and the scant attention given to curriculum; the text makes a valid point that these teachers succeeded in spite of, not because of, the Institute.

All aspects seem to point to assimilation into colonial society, in service roles specifically, whether as household help, labourers, or military. Even the cadet corps period, introduced to address the “lack of discipline,” was seen to promote and reinforce assimilation.

It is of interest that when lands were sold, the proceeds went not to improve conditions at the Mohawk Institute, but to build another school elsewhere. Also of interest among the artifacts uncovered were letters to home.

Canada, we read, appears to be a nation founded on an attempt to erase Indigenous identity, and yet Canadians still think of themselves as “nice and polite.”

From the opening poem, in which David Monture speaks of being “made to feel ‘The Other,’ in our own homeland” to that powerful concluding line in the poem by Jimmy Edgar, “May your God forgive you, oh Canada, for I cannot,” through each painstaking detail, this is a book that cannot and must not be ignored.

This book provides a powerful reminder that to have truth and reconciliation we must not only read these things but know these things and change our lives in this knowledge. Let us listen, learn, and act.

About the Author

Richard W. Hill Sr., Tuscarora Nation of the Haudenosaunee, is a community-based historian at Six Nations of Grand River.

Alison Norman is a settler historian who works for the federal government at Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

Thomas Peace is an historian at Huron University College and an editor at ActiveHistory.ca.

Jennifer Pettit is Dean of the Faculty of Arts and professor of History and Indigenous Studies at Mount Royal University.

About the Reviewer

Anne M. Smith-Nochasak grew up in rural western Nova Scotia, where she currently resides and teaches part-time after many years working in northern communities. She has self-published four novels using Friesen Press’s services: A Canoer of Shorelines (2021), The Ice Widow (2022), and two instalments in the Taggak Journey trilogy: River Faces North (2024) and River Becomes Shadow (2025). She is currently a member of the Writer’s Federation of Nova Scotia and likes to feature Nova Scotia settings in her writing. When she isn’t writing or teaching, Anne can be found reading, kayaking, gardening, renovating, or exploring the woods with her golden dog Shay while her cat Kit Marlowe supervises the house. Anne can be reached through her website https://www.acanoerofshorelines.com/ or on X, IG, and FB.

Book Details

Publisher : University of Calgary Press

Publication date : Sept. 1 2025

Language : English

Print length : 528 pages

ISBN-10 : 1773856529

ISBN-13 : 978-1773856520