Choose Life: A Review of Child of War

Reviewed by John B. Lee

“I call heaven and earth to witness you today: I have put before you life and death, blessing and curse — therefore choose life!” (Deuteronomy 30:16)

Every once in a while, I have the privilege of reading a book which I might well describe as essential. A book so profound, so real, so true, so authentic, so deeply moving, so morally good as to render its presence in my private library and in my edified imagination as though it had always been there, simply waiting for the reader to reify the text as received, an affirmation of our common humanity, thereby establishing a deep connection, a bond between myself and the author.

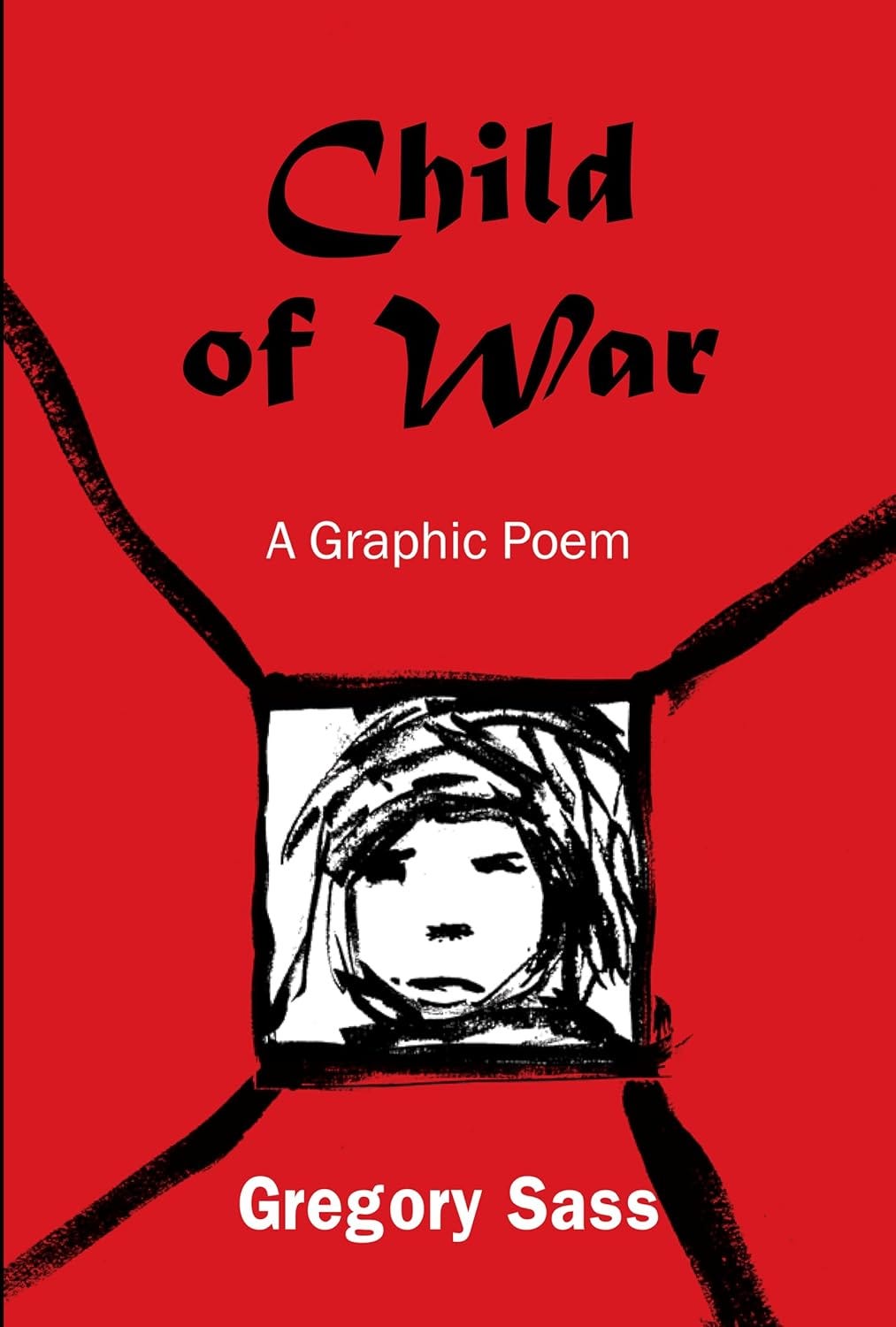

And Child of War by Gregory Sass is just such a book – a book not born in the library, but born into the world, from a world which does not love us well, a world where the death cult of Nazism has taken hold on life, where the master race might be heard saying “We love death more than you love life.” And Gregory Sass, born in Berlin in 1938 gives us the story of a child who survives the worst years in an awful place, only to suffer the aftermath as a child of post-war depravation and suffering to emerge from that devastation, to look back and write about what it meant to be a child of war, as he says in an epigram quoting Eglantyne Jebb, “Every war is a war against children.”

“And Child of War, however bleak, however horrifying, however terrible, is an example of a book which defeats the very evil which it embraces.”

As he writes in the opening poem “To Annabelle Bann”: “Ask the big questions and arm wrestle with God.” This phrase echoes the title of Jordan Peterson’s recent book We Who Wrestle with God, which is something of an exegesis inspired by the story of Jacob in the Bible. And the suffering of the child within the man, the private experience of Gregory Sass from his birth through his formative years, is a dark reminder of dark times. It is a bleak recollection of grim experience, emerging into the light, a light he carries with him, a light which illuminates the interior world of a child in darkness, a light which radiates into that outer darkness revealing the evil that lurks in the shadows, an evil which is, in the words of the poet Milton “darkness visible.” And although this is a difficult read, it is important that we be reminded by these poems, and by the drawings which sully the pages with images that horrify, edify, affirm that we must linger long enough to apprehend that which is so difficult to comprehend. That is our capacity for evil, as manifest in times of war, and thereby be reminded of our individual and collective capacity for good. To emerge as triumphant, in the words of scripture, to “choose life.”

If evil may be said to be that which makes the worst from the best, then what good might be said to be that which makes the best from the worst. And Child of War, however bleak, however horrifying, however terrible, is an example of a book which defeats the very evil which it embraces. One might well beware, as Nietzsche warns us “He who fights with monsters should see to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into the abyss, the abyss gazes into you.”

In his poem “The Great Flight,” the author reminds us:

You are not alone whenever you walk this ground, soaked with the blood, sweat and tears of those who were here before. Honour them by knowing them and letting them touch your soul

And this is a book of then and now, a book of us and them. It reminds those of us privileged to have come of age in a stable nation at a time of peace, as in the words of Douglas Murray from his book On Democracies and Death Cults: Israel and the Future of Civilization, “Some people never get a chance to be weighed in the balance.” And so one may well ask, “who would I have been, and what would I have done, if I had lived in such a time and in such a place?”

Sass was born into a world where the temporary aberration of bad governance given over to the admiration of the monster who gave the world ‘the final solution,” the death of nearly sixty million people mostly civilians, a man whose portrait appears in blotches of ink opposite the poem “The New Germany,” a man who extoled with great admiration the quintessential Nazis praising him as “the man with an iron heart.” The closing line of that horrific poem “Democracy is destroyed in 53 days.” And is it not prophetic of our times, though it refers to the year 1933? As we move through poems inspired by “Kristallnacht,” “Stalingrad,” ‘The final solution,’’ “Auschwitz,” “The Sinking of the Gustloff,” “Retribution,” “The Great Flight,” into a time of scabies, lice, hunger, diphtheria, homelessness, “Hiroshima,” tuberculosis, and from there into a time of reconstruction posing the question “How did we—each of us alone – keep going/ when there was little to support us?” Good question, well answered. In the poem addressed to his mother near the end of the book he chooses to say “thank you/for giving me life/for loving me … for teaching me to read/ and to love books/ thank you/ for the Sunday mornings/ when you made/ sharing an egg and a bun/ into a feast.”

In the end, in the final analysis, in the face of horror and suffering – gratitude – for the gift of life is an affirmation, despite that which breaks some of us, makes us feel we are victims, as he writes in his poem “There are reasons:” “I was born too late/ to do harm, cannot escape/where I come from/ and what was done by my people./ My soul was poisoned,/ but I always look at myself/ and atone with care./ I am not Sisyphus.”

In his book Man’s Search for Meaning, Victor Frankl makes the poignant observation concerning the prisoners in concentration camps “those who shared their bread were more likely to survive than those who stole bread from others.” So, what might we learn from Sass’s masterpiece? In his author’s profile he opines “Current events often remind him of his own experiences as a child of war.”

Many years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, I took advantage of the opportunity to inquire of my Cuban friend and contemporary Manuel Leon, “What was it like for you in Cuba in October 1961?” He was almost exactly my own age, and being a farm boy like me, he spoke of working in the fields while the American planes flew overhead, with his mother calming him and reassuring him that everything would be alright in the end. Unlike me, he did not have access to the news, nor was he subjected to the fear-mongering by the chattering classes, warning of nearly inevitable consequences of mutually assured destruction.

And so it goes. And so it was. And so it went. And so it seems it will ever be for children of war. In my mind, warfare is always a failure of the human imagination. The book Child of War reminds us that evil is within us, as Gregory Sass writes in his poem “Marked,” “It is endlessly here: the secret of evil …”. Reading this book is both an antidote and an anodyne. For those of us who have never suffered the realities of war at home, when we weigh our hearts in balance with the heavy-hearted, though our hearts be light, still we too may embrace love and shout, “Choose life!”

About the Author

Gregory Sass emigrated with his family to Canada from Germany at age fifteen in 1953. The Canadian Forum published his first poems two years later. Greg became a Canadian citizen by Act of Parliament in 1956. Since then, he has written and published twelve books — Canadian history, special education, and poetry. In his retirement, he lives communally in Thornhill, Ontario. Current events often remind him of his own experiences as a child of war. With this illustrated epic tale he advances poetry into new directions

About the Reviewer

John B. Lee, in 2005, was inducted as Poet Laureate of Brantford in perpetuity. The same year, he received the distinction of being named Honourary Life Member of The Canadian Poetry Association.

Book Details

Publisher : Silver Bow Publishing

Publication date : Aug. 21 2025

Language : English

Print length : 124 pages

ISBN-10 : 1774033534

ISBN-13 : 978-1774033531