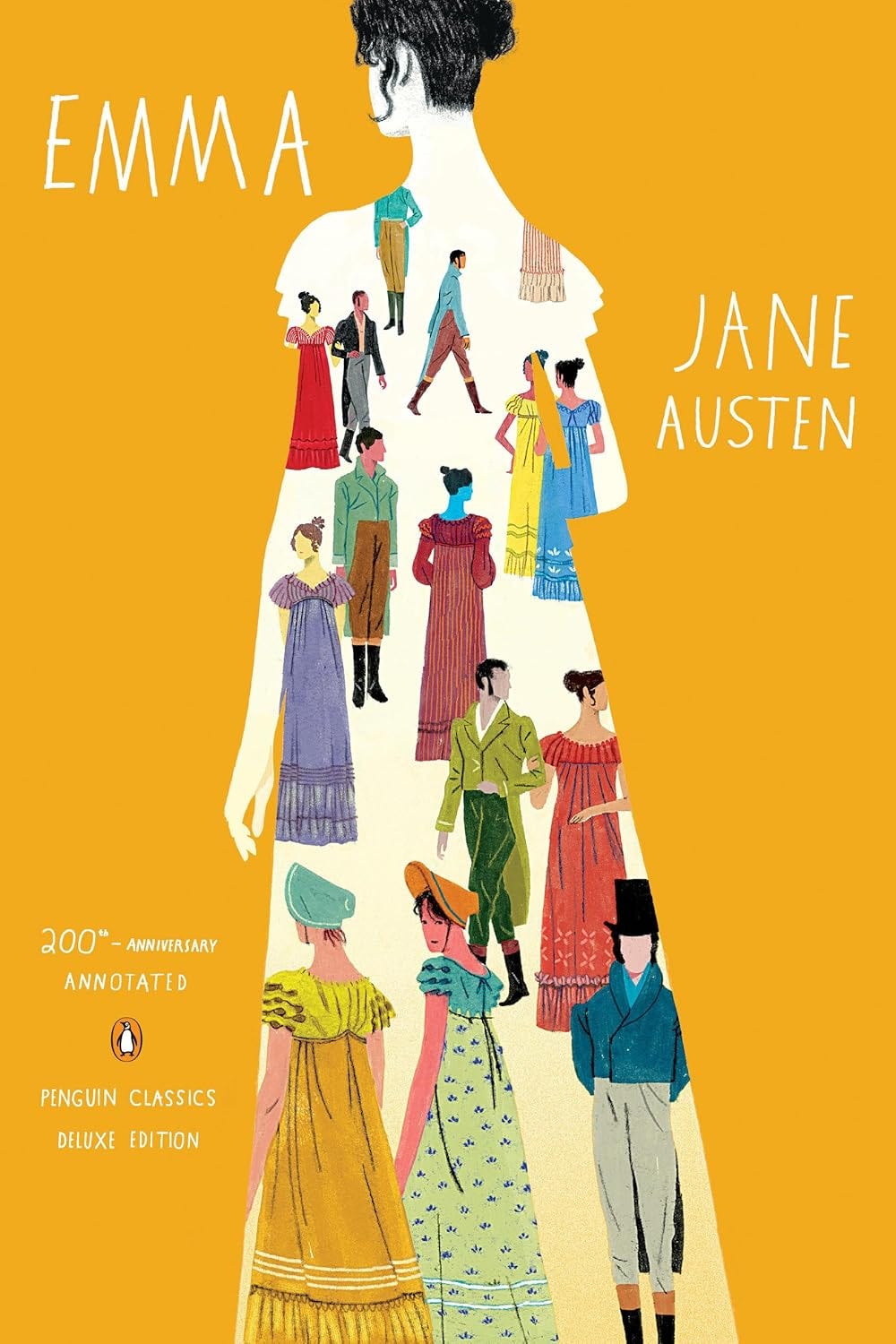

Emma by Jane Austen (200th Anniversary Annotated Edition)

What is it about Jane Austen’s fiction that appeals to writers as diverse as Mordecai Richler and André Alexis?

What is it about Jane Austen’s fiction that appeals to writers as diverse as Mordecai Richler and André Alexis? After 200 years, her polished prose, social satire, and psychological insights endear her to readers across the board. Emma Woodhouse, the eponymous protagonist in her novel, balances between a romantic softness in her given name and a harder domestic confinement in her surname. The opening balance of syntax and punctuation guides the reader: “Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.” The sentence’s orderliness is poised – poised to fall at any given moment, for Emma is separated from her predicate by several adjectives that function like so many chess pieces on her checkerboard of experience and grammar. The first triad of qualifiers builds to “rich,” which has its own satirical drop before expanding to the comfortable home or Woodhouse where character and setting are united. The principal verb “seemed” highlights the potential for illusion and vexation amidst superlatives. This idyllic architecture continues after the semi-colon, culminating in the dismissal of distress and vex, which lurk around Emma. For Emma is a matchmaker who meets her match in Jane Austen who possesses a manor and manners of her own, and who unifies her novel from the opening “unite” to the final “fully answered in the perfect happiness of the union.”

“Emma looks backward to Shakespeare’s comedies of errors and Alexander Pope’s mock-heroic couplets, and forward to Dickensian eccentricities and Virginia Woolf’s streams of consciousness.”

Emma looks backward to Shakespeare’s comedies of errors and Alexander Pope’s mock-heroic couplets, and forward to Dickensian eccentricities and Virginia Woolf’s streams of consciousness. Emma’s first blunder in matchmaking concerns Harriet Smith and Mr. Elton. She advises her friend Harriet that the match is a certainty, based on her sound judgment, which is ironically supported by literary examples that undercut her claim: “It is a sort of prologue to the play, a motto to the chapter; and will soon be followed by matter-of-fact prose.” Austen’s prose mixes the matter-of-fact and the romantic, and embeds mottos and prologues where Shakespeare’s “The course of true love runs smooth” makes its way to Hartfield, home of the Woodhouse family. After Emma quotes that line from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, she concludes that “A Hartfield edition of Shakespeare would have a long note on that passage.” And indeed, Austen’s three volumes constitute that long note in which the heart runs errantly and smoothly in the field.

Ultimately the air of Hartfield “gives love exactly the right direction,” but not before that flow is misdirected. Under the direction of Knightley, Emma eventually unlearns her mistaken ways. Without a mother to guide her, she relies on her governess, Miss Taylor, who marries Mr. Weston and leaves her and her father. Emma is blind to her own faults: “The real evils indeed of Emma’s situation were the power of having rather too much her own way, and a disposition to think a little too well of herself.” She boasts to her father and Mr. Knightley of her success in making the match between Miss Taylor and Mr. Weston. In response to Emma’s proposal to find a wife for Mr. Elton, Mr. Knightley’s aphoristic pronouncement closes the opening chapter: “Depend upon it, a man of six or seven-and-twenty can take care of himself.”

Chapter II opens with a description of Mr. Weston: “Mr. Weston was a native of Highbury, and born of a respectable family, which for the last two or three generations had been rising into gentility and property.” Highbury refers not only to geographic heights but also to status in society, while “bury” is a reminder that all such risings come to an end with each generation. Austen’s balanced syntax and sentence structure works in tandem with the polarity of high and low, any elevation held in check by gravity. Austen blends romantic realism with ironic overtones in her signature style, replete with qualifiers in the form of balancing adjectives or “but” clauses. Of the original Mrs. Weston: “but though she had one sort of spirit, she had not the best.” Followed by – “She had resolution enough to pursue her own will in spite of her brother, but not enough to refrain from unreasonable regrets at that brother’s unreasonable anger.” Reason’s balancing act finishes with the third and fourth ironic, measuring “but,” a fulcrum that disrupts equilibrium: “They lived beyond their income, but still it was nothing in comparison of Enscombe; she did not cease to love her husband, but she wanted at once to be the wife of Captain Weston, and Mrs. Churchill of Enscombe.” Drawing on Pope’s balanced verse, Austen’s social satire is measured in neo-classical rhetoric and Regency prose – the architecture of class structure in Highbury, Surrey and Enscombe, Yorkshire.

Mr. Weston’s son, Frank Churchill, comes under close scrutiny: “He was looked on as sufficiently belonging to the place to make his merits a kind of common concern.” Since he rarely appears in Highbury, his belonging is highly questionable, while common concern carries overtones of gossip among classes and villagers. In lieu of visiting, Frank Churchill writes to his new mother who spreads the word among the locals, and the narrator comments on village gossip: “For a few days every morning visit in Highbury included some mention of the handsome letter Mrs. Weston had received.” “Handsome” makes the rounds as a sardonic touchstone in recorded conversation: “I suppose you have heard of the handsome letter Mr. Frank Churchill had written to Mrs. Weston? I understand it was a very handsome letter, indeed. . . Mr. Woodhouse saw the letter and he says he never saw such a handsome letter in his life.” Avant la lettre, and before the invention of telephones, Austen’s missives highlight an epistolary tradition. Narrative commentary exaggerates characters’ commentary, and Highbury’s handsome ways are exposed. The chapter ends with a postscript to the Westons’ wedding: “There was a strange rumour in Highbury of all the little Perrys being seen with a slice of Mrs. Weston’s wedding-cake in their hands: but Mr. Woodhouse would never believe it.” Hypochondriac Woodhouse believes in Mr. Perry, the apothecary, who is consulted by everyone even though he never actually speaks in the novel where strange rumours contend with unbelievable truths and slices of life. Once again, the pivotal “but” unhinges pretense and caps off satire.

Chapter III turns from his disbelief to more of his foibles: “Mr. Woodhouse was fond of society in his own way.” What is Woodhouse’s way? Austen’s fondness for circumscription of character, place, and prose arrives as an answer: “He liked very much to have his friends come and see him: and from various united causes, from his long residence at Hartfield, and his good nature, from his fortune, his house, and his daughter, he could command the visits of his own little circle, in a great measure as he liked.” Austen circumscribes her circle and extends it to a great measure from united causes to fortune in wealth and fate, and a narrative command of vistas. Garrulous Miss Bates contrasts sharply with the opening description of Emma: “a woman neither young, handsome, rich, nor married.” Emma’s foil “was a great talker upon little matters, which exactly suited Mr. Woodhouse, full of trivial communications and harmless gossip.” Austen’s ironies measure the distances between great and little, grandiloquent pretension and pettiness.

If Miss Bates comes under scrutiny, so too does Mrs. Goddard in a lengthy sentence that incorporates “long sentences” in self-awareness: “Mrs. Goddard was the mistress of a School – not of a seminary, or an establishment, or any thing which professed, in long sentences of refined nonsense, to combine liberal acquirements with elegant morality upon new principles and new systems – and where young ladies for enormous pay might be screwed out of health and into vanity – but a real, honest, old-fashioned Boarding-school, where a reasonable quantity of accomplishments were sold at a reasonable price, and where girls might be sent out of the way and scramble themselves into a little education, without any dangers of coming back prodigies.” Pope, Swift, and Dickens fit within the sentence’s satire, while Austen’s dashes are forerunners of Emily Dickinson’s dashes later in the century. Austen’s dashes stretch her sentence and provide breathing space for reflection and consideration. In this sentence they offer an excursion into what the school is not, and serve as a critique of educational systems of refined nonsense. “Enormous pay” contrasts with “little” education in the second half of the sentence introduced by “but” and landing on “reasonable” quantity and prose. In short, Mrs. Goddard’s Boarding-school is real, honest, and old-fashioned – the very qualities and ironies of Jane Austen’s novels.

For her father’s sake, Emma is content to collect these women, “but the quiet prosings of three such women made her feel that every evening so spent, was indeed one of the long evenings she had fearfully anticipated.” Quiet prosings of guests contrast with Austen’s quiet prose of whispered ironies. This participle recurs in an emotional exchange between Harriet and Emma on the question of marriage, as an agitated Emma internalizes and projects Miss Bates’s dashes: “if I thought I should ever be like Miss Bates! so silly – so satisfied – so prosing – so undistinguishing and unfastidious – and so apt to tell every thing relative to every body about me.” “About” underscores circumlocution as well as circumscription, while Emma’s prose oscillates between discernment and melodrama in her quest for truth amidst a blindness filtered through class distinctions. Her rhetoric of parallelisms expands so’s to negative polysyllables and relates “every” to encircle surroundings. Emma remains vehement about “any likeness” between herself and Miss Bates, and likenesses play out in the novel’s paintings and representations of physical and psychological resemblances.

Although Emma is determined to remain unmarried like Miss Bates, she assures Harriet that she will never be a “poor old maid” because she does not have “a very narrow income.” Her financial status affords her a degree of freedom in a manner of her own: “but a single woman, of good fortune, is always respectable.” Financial fortune determines fate’s fortune. Emma’s style appears aphoristic, but her repetition of phrases questions aphorism and judgment, for she will not remain unmarried. If “a very narrow income has a tendency to contract the mind,” then broadening money expands irony in the circumscription of mind and destiny.

A dynamic between circumscription and circumlocution contributes to the rhythm in Emma. The protagonist pins her hopes on her sister’s children, the nieces and nephews of a displaced parenthood. Where Emma is childless, her sister has an abundance of offspring. When Emma concludes that she will often have a niece with her, Harriet shifts the dialogue to Miss Bates’s niece, and Emma replies: “that is almost enough to put one out of conceit with a niece.” This niece conceit revolves around Jane Fairfax whose very name sickens Emma because “her compliments to all friends go round and round again.” Once again, circumlocution interferes with circumscription. This dialogue between Emma and Harriet follows their earlier one that reflects upon Mr. Elton’s character, itself a form of chatter, riddle, prosing, and writing. Emma is certain that his charade is meant for Harriet: “Receive it as my judgment.” Her Shakespearean lines are undercut by her faulty judgment where “matter-of-fact prose” is blinded by romantic illusions and deceptions. Emma’s linguistic matchmaking includes repetition in “common sense” and “common phrase” as she mentally arranges a likeness between Harriet and Mr. Elton. Their alliance would settle them in “the same county and circle,” with a “comfortable fortune.” Emma’s and Harriet’s dialogue becomes itself a charade on Mr. Elton’s charade. They consider it “the best charade” they’ve ever read, and an infatuated Harriet doesn’t even hear Emma’s estimation: “I do not consider its length as particularly in its favour. Such things in general cannot be too short.”

Their literary criticism forms part of this comedy of errors and manner. With “cheeks in a glow,” Harriet proclaims that it is one thing “to have very good sense in a common way, like everybody else, and if there is anything to say, to sit down and write a letter, and say just what you must, in a short way; and another, to write verses and charades like this.” Emma writes letters long and short, but it is also a charade concealing and exposing its own Shakespearean indebtedness. If Emma approves of Harriet’s “spirited rejection of Mr. Martin’s prose,” Austen exposes this rejection when Harriet eventually accepts Mr. Martin’s good sense and prose in matrimony. Harriet wants to copy in her book Elton’s charade, which is itself a copy of a friend of his. This charade exemplifies misplacement and displacement in the novel.

As the second child, Emma is consumed by firsts. Emma, “never loth to be first,” takes Elton’s paper and reads: “My first displays the wealth and pomp of kings.” This charade’s first line focuses on “first” and wealth on earth, before the quatrain turns to the seas: “Another view of man, my second brings, / Behold him there, the monarch of the seas!” The reversal or reconsideration of first and second leads to the sestet: “But, ah! United, what reverse we have!” Reversal and union are at the core of the novel, as the charade turns to the power of woman over man, and concludes with a couplet that Harriet cannot copy in her book: “Thy ready wit the word will soon supply, / May its approval beam in that soft eye!” The couplet beams and blinds Shakespeare and Pope, after the transference of power from masculine earth and sea to the woman who “reigns alone” (with the double sense of alone). The charade encapsulates that delicate balance of syntax that destabilizes sense and sensibility.

After the two women exhaust their interpretation of this charade, Mr. Woodhouse enters the stage to share his own interpretation of these words. Emma tells him parenthetically that the paper was “(dropt, we suppose by a fairy),” whereupon he guesses that the fairy in question is Emma herself – yet another example of misattribution in the novel. Convinced that this daughter penned the words, he tells her that she takes after her mother who “was so clever at all those things!” With his faulty memory, he can remember only the first stanza of another riddle, “Kitty, a fair but frozen maid.” The chapter concludes fittingly with contrasting reactions of Emma and Harriet to Elton’s words: “there was a sort of parade in his speeches which was very apt to incline her to laugh. She ran away to indulge the inclination, leaving the tender and sublime of pleasure to Harriet’s share.” This charade and parade of language arouse mirth in one and the sublime in the other, with the sublime eventually lowered to the ground of reality.

The next chapter lowers the romantic sublime when Emma and Harriet pay a charitable visit to a poor sick family outside of Highbury. Their way passes Vicarage-lane where Mr. Elton resides in a “blessed abode.” After a “few inferior dwellings … about a quarter of a mile down the lane rose the Vicarage; an old and not very good house …. It had no advantage of situation; but had been very much smartened up by the present proprietor.” The down and up of domestic description reflects the social structure within Highbury’s community. (Austen’s influence on Alice Munro seems almost unmistakeable.) After the charitable visit, Emma declares that the impoverished family has made a lasting impression on her as she crosses the “tottering footstep which ended the narrow, slippery path through the cottage garden.” After this fallen garden, they come upon Mr. Elton who is on his way to visit the poor, their common purpose aligning with the coincidence. In an aside Emma thinks, “To fall in with each other on such an errand as this.” She wishes she were anywhere else so that Harriet and Mr. Elton could be together alone. Elton is the serpent in the garden, and Emma thinks, “Cautious, very cautious … he advances inch by inch, and will hazard nothing till he believes himself secure.” In this erroneous love triangle, none of the characters has partaken of the tree of knowledge.

Frank Churchill fixes Mrs. Bates’s spectacles, as described by Miss Bates: “there he is, in the most obliging manner in the world, fastening in the rivet of my mother’s spectacles. – The rivet came out, you know, this morning. – So very obliging! – For my mother had no use of her spectacles – could not put them on. And, by the bye, every body ought to have two pair of spectacles.” Seemingly as redundant as the second pair, her comic stream of consciousness flows though dashes and exclamation marks, as if everyone ought to have two sets of ears for her mouth that Emma rivets in an insult. Yet the reader needs the corrective lens of two sets of spectacles in re-reading the novel, looking forward and backward though Emma’s blindness. Running off at the mouth, Miss Bates cannot follow her own train of thought, and “Emma wondered on what, of all the medley, she would fix.” In all the senses and sensibilities, Austen matches oral and visual fixes in her ironic repair of language.

Accordingly, circumspection enters the novel alongside circumlocution and circumscription. Jane Fairfax fixates on the post-office, a site of transference of clandestine letters from Frank Churchill. In her exchange with John Knightley, she opines that “Letters are no matter of indifference; they are generally a very positive curse,” and that oxymoron captures some of the irony in the novel’s letters. With similar ambiguity, Jane replies, “a post-office, I think, must always have power to draw me out.” Jane is drawn out in more than one sense, as she explains, “The post-office is a wonderful establishment!” (Austen would have been attached as well to this site of circulation.) Jane continues to rhapsodize over this astonishing institution: “So seldom that any negligence or blunder appears! … And when one considers the variety of hands, and of bad hands too, that are to be deciphered, it increases the wonder!” She is referring to the contents of letters as well as addresses on envelopes, for both have to be deciphered to prevent blunders. These bad hands are metonymies of the letter writers themselves, the characters of the alphabet and society. Emma responds to this spirited exchange about a gentleman’s hand-writing with reference to Frank Churchill: “Is it necessary for me to use any roundabout phrase?” This circumlocution examines the circulation of letters; and the interplay between oral and written texts concludes the chapter: “She could have made an inquiry or two, as to the expedition and the expense of the Irish mails; it was at her tongue’s end – but she abstained.” The tongue’s end ends the chapter on a note of speech withheld, and the secrets of Irish males.

Frank Churchill’s letter to Mrs. Weston serves as a kind of postscript to the discussion of the postal service. He detects his own blunder, and raves “at the blunders of the post.” He concludes by referring to Emma who calls him “the child of good fortune” – yet another of these children and adults who possess fortune of one sort or another. In this case, his “good fortune is undoubted, that of being able to subscribe myself.” His subscription, an under-writing, joins forces with all of the circumscriptions that circulate throughout the novel. His ability to subscribe himself is both postscript and prescription for behaviour, with or without the assistance of Mr. Perry, the apothecary who cures all.

By the end of the novel Harriet’s “stain of illegitimacy” seems to be removed, but there are too many indelible markers in the book to be forgotten. One of them is the erased or invisible mother. Mr. Weston’s “conundrum” directed at Emma questions parentage: he asks what two letters of the alphabet express perfection, and the answer is “M. and A. – Em – ma.” These letters refer not only to a Master of Arts and the degree to which one can master the arts, but also to the abbreviated absent mother or Ma. Accordingly, Emma cannot inherit or transmit perfection, or complete the novel’s circles. Harriet’s telling details to Emma contain the “tautology of the narration” – a narrative tautology that recurs in repetition from firsts to circles in the sameness of words. Mrs. Elton repeatedly boasts about her past at Maple Grove where people move “in the first circle.” Later, the narrator takes up her words to Jane Fairfax: “Delightful, charming, superior, first circles, spheres, lines, ranks, every thing.” Narrative tautologies circumlocute and satirize the geometric structure of society, as Austen penetrates pretension and upends Mrs. Elton’s barouche-landau.

From its colourful cover and fine-cut pages to Juliette Wells’s informative essays, this Penguin Classic edition is a handsome, welcome addition for Janeites and other readers.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Penguin Classics

Publication date : Sept. 29 2015

Edition : 200th ed.

Language : English

Print length : 496 pages

ISBN-10 : 0143107712

ISBN-13 : 978-0143107712