Four-Square Poems by James Deahl

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

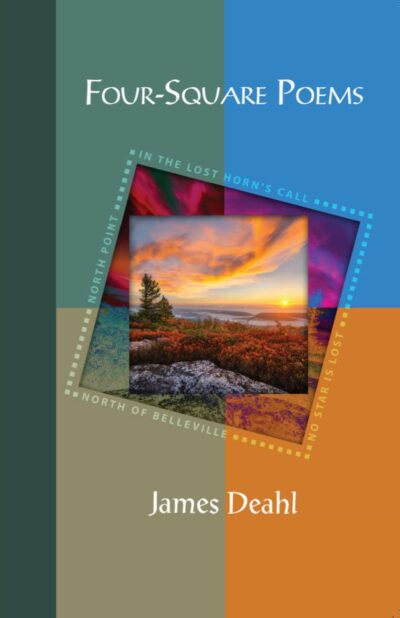

After William Blake’s The Four Zoas and T. S. Eliot’s “Four Quartets,” James Deahl measures symmetry in Four-Square Poems. The book’s four sections encompass a symmetry of “lost” and “north”: In the Lost Horn’s Call, No Star is Lost, North of Belleville, and North Point. In addition, the brilliant and subdued colours, frames, and shapes on the book’s cover capture the spirit of northern loss in the poems – four score of an extended life span.

“Deahl is a poet of disappearances in early dusk, utter blackness, hidden darkness, harvest evening, abandoned orchard, empty school yard, aftermath of storm, white birch blown bare, grey water, and a silent TV that sustains middle-aged men. His compass points in the direction of Al Purdy.”

The opening poem, “Prelude,” paints a picture of winter through sound, precise diction, and drifting lines. The first stanza surrounds the indented line and land: “There are passages through winter / The clarity of snow / is cut by the thin edge.” While the “j” in edge and passage grasp snow in preparation for the standout colour “magenta,” the “r” sounds in There, are, through, winter, and clarity control the halting flow through the stanza’s second half: “Snow drifting over stubble, / the texture of earth / before the wind.” The absence of periods allows the reader to close sentences and stanzas, to pause at the various passages of time, tone, and text – the cadence and choreography of “the dance of / beauty.” In the second half of the poem acute magenta eyes cut through a white landscape with a large anger that contends with “thin edge.” The weight of the last lines bears downward: “Ah, woman, / slipping into nebula / you are bone.” On another level, the poem is a biblical passageway with Eve reduced to rib in a frozen Eden, a fluency of lake and land.

The machine in the garden appears in “One”: “Toronto, 1976 (mark of transport and commerce) / We sweep the garden / or do nothing at all.” Deahl colours his female figure in magenta or fire – “her hair is aflame / with wildbrier.” Figures appear in a single “sharp instant” of spontaneous combustion igniting a landscape of emotion. Numbered poems from “One” to “Six” in “The Lost Horn’s Call” reveal themselves like photographs surfacing from a dark room in black-and-white or colour. The negatives develop slowly then spontaneously, revealing the poet’s fraught relationship to a woman who appears as “Firemaker” in a “burning house” or “water ensnared fire.” She takes the form of Lilith “with red edgings,” “red shard,” “scarlet hawthorn / the luminous crimson” of The Scarlet Letter. She is “the fire pouring / incandescent,” “the bruised flame,” and blood.

Visually, these poems fit within the four-square frames on the book’s cover with their “wide range of colours and textures.” Aurally, “In the Lost Horn’s Call” sounds a history of personal and national entropy, syllables receding in red cliffs and pink flesh. That call may emanate from a lighthouse with a foghorn piercing the mists. Or it may blow into Toronto’s Kensington Market with its still lifes of fruit and motion of nationalities with their dance of words. Gyrations of civilization wind through stanzas: “we call up distant sea threaders / mists of islands” that recall “The Minoan world, / lifting high / the sacred snakes.” Deahl raises the stakes to Stonehenge with its circles, rings of women, and archival call. After invoking the Statue of Liberty and Delacroix, the poet returns to the corner of Augusta and Nassau, where “she is water ensnared fire” – the elemental feminine in the lost horn’s call. Deahl’s pigments and rings of song emanate from the lost horn.

The second section, “No Star is Lost,” reiterates the poet’s elegiac sense of loss. A. E. Housman’s lines serve as epigraph to this section: “No star is lost at all / From all the star-sown sky.” The “Prologue” probes the mystery of life and death, and lifts detail into clarity. The poet is drawn to “improbable relationships” between human beings, between speaker and nature, and between the tenor and vehicle of metaphor. In “Camp Chapel” an elegiac note is struck through incantatory parallelisms: “Not so much a sadness, but / a longing for forfeited innocence.” The sorrow of a great dream leads to “as if only loneliness welcomed us.” This autumnal meditation deepens meaning through negatives – “Not so much grief, / but a recognition of limitation.” Circling the seasons, Deahl writes his own Ecclesiastes. “Dolly Sods” ruminates between physical world and metaphysical speculation in the mode of Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” Bird and tree constitute the landscape “and lead to an understanding of the intelligence that / placed them at the cliff’s edge so that they made the cliff’s edge / and were the cliff’s edge, always ready / as if the transcendent would become incarnate at any, even this, instant.” These long lines of understanding build up the cliff’s edge, which becomes the source and site of insight and revelation for a Thoreau of the farther north.

“North of Belleville,” shortest of the four sections, relies on minimalist tercets to describe the scenery and set the mood. Katherine Gordon’s epigraph introduces the poem: “The stars that lent us dust / sing in our blood.” Deahl’s first tercet sings between dust and blood: “Smoke from a highrise / straight into frozen air -- / fields of bitter weeds.” Visuals from smoke and highrise meet fields of weeds, but the sounds capture these sights in long vowels (i, o, e) and clutching r’s – highrise, straight, frozen, air, bitter. And the long dash marks the sudden transition from skyline to grounding fields. Deahl is a poet of disappearances in early dusk, utter blackness, hidden darkness, harvest evening, abandoned orchard, empty school yard, aftermath of storm, white birch blown bare, grey water, and a silent TV that sustains middle-aged men. His compass points in the direction of Al Purdy.

He continues his northern quest in the final section, “North Point,” with its 14 meditations in memory of Tom Thomson. This sequence enters into a dialogue with Thomson’s paintings. The first brushstroke in “The Jack Pine” – “Always a lake.” – a short sentence with long a’s and a hard k to echo Jack. The second sentence lengthens the line through parallelism, another “k” in rock, and a series of r’s to gird the canvas: “Always the rock / bare and severe.” The third sentence continues the parallel brush stroke, lengthen long a’s, and grasps r’s in renegade and storm: “Always a renegade pine / shaped to wind and storm.” The pine is the poet is the painter – each a renegade refusing to succumb to overwhelming forces of nature. This hammering home of “always” guarantees a permanence and fixity against the shifting seasons and elements. The pine is a solitary symbol, a still rootedness that embraces “our station, / our emblem / and point of pilgrimage.” The paradox of the fixed pine as pilgrim of meaning works in tandem with monosyllables that syncopate with longer renegade and pilgrimage.

Here on this jut of earth we begin and end, like any year, its cycle starting and finishing on that shortest day of all.

Within a four-square frame, brushstrokes cycle the tree which pines for the unknown north point.

The second stanza paints spring with a residue of winter on the lake. A sentence begins with pine and ends with pioneer to echo and mirror its lyrical greening. Deahl’s verticals move from “a pioneer rising” at the end of the stanza to a falling in the next: “Such a sky one seldom sees / at other seasons tumbles.” The Canadian canvas stretches: “is filled with a sweep / of opulent darkness / stretching from the Great Lakes / to the Mackenzie.” This sweep of the Canadian Shield is also a cleansing of the north, yet the final stanza places humanity in the landscape, the poet lost in time but found in place: “And so an image comes / of a man lost in time, / fishing stream or lake shore snagged with deadfalls.” An undertow of sunken logs, meditative reserve, and “a better life from below” ripples through “The Jack Pine,” only to surface at the end with its ladder of hope:

Morning comes, its slanting light closing from sight all that moves beneath the beaten surface, all that exists in a breath as possibilities of air.

The sentence swims through slanting and surfacing, beneath and beaten, to breath the “always” at the beginning.

The jack pine reappears in “Burnt Country, Evening” where fire fills the possibilities of air. A burnt brushstroke sweeps the canvas: “The great fires have swept past / bringing purification to the forest.” Deahl’s sweeping verse finds catharsis in Thomson’s verticals of toppled timber and upright trunks. If everything seems seared, blistered, and charred, then the second stanza offers relief: “Soon jack pine cones will open / to reclaim their land from the hand / of flame.” If the painter traces scene, the poet’s voice spins the long o’s of cones. Images of land, hand, and flame create their own choreography: “All remains still / where fires have danced, the sky / as grey as smoke.” This still dance echoes stasis and continuity to enter the final stanza: “This is the ballet of rebirth / that continues without us.” The ballet of balance concludes in chiasmus: “we end in fire / and in fire find our beginning.”

“The Waterfall” paints sounds and silence through cadenced b’s and d’s in birdsong, unbroken, and Beethoven syncopated against woodland, dense, dark, silenced, strident, shadow. Added to these colours are long o’s to stretch Beethoven’s sounds of “dark tones, strident / in their cloak of shadow.” Beethoven’s sonorous deafness combined with Thomson’s enigmatic brushstrokes create a mystery at the forest’s heart. Conifer and rock jut turn transcendent: “To enter this land / is to open the door / to another life.”

Algonquin and Canadian Shield lend themselves to metaphysical meditation in each of these poems. “Tea Lake Dam” questions the last and lasting effects of Thomson’s paintings. After the colour of sky and river the poem shifts from canvas to contemplate “Earth and water through their passion / turn into air and spirit, and then comes / the astonishing grace of transcendence / with this land the threshold we pass over.” That passage and sentence are followed by the final stanza with “human vision bordering on revelation.” And a coda or aftermath for a Canadian cosmos: “Days later his vision ends in death.”

Deahl’s palette of tropes: flames, crimson dance, and meditation of bright colours in “Red Sumac”: “The sumac blazes the way lust / and love twist together into their / incandescent filigree of desire.” The ekphrastic extrapolation of oil on canvas thickens into other shapes of sound, emotion, and re-interpretation of dreams.

Seamus Heaney enters “Petawawa Gorges” to offer glimmerings north of Highway 7. Like a compass needle, brush and bush point north in “Grey Day in the North” or “The West Wind,” which looks back to Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ode. The poem concludes with “Winds shift from north-northwest to southwest, / and riding the heady spring gusts / a mated pair of northern goshawks / head even further north.” If the sun-treader appears, can Deahl be far behind in his fourfold vision of a lost and found northland?

About the Author

James Deahl is the author of some 20 poetry collections. In 2001 he received the Charles Olson Award for Achievements in Poetry. In 2012 Rooms the Wind Makes appeared, and in the same year he edited The Selected Poems of Milton Acorn for Mosaic Press. He lives in Sarnia, Ontario.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published extensively on Victorian, Canadian, and American Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

To order a copy of Four Square Poems, email info@aeolushouse.com

Publication Date: 2025

Publication Information: Aeolus House

Physical Description: 82 p.

ISBN: 9781987872705

Surely no one could resist the promise implicit in "there are passages through winter" - not ways of finally escaping it but of a meaningful encounter along the way - never mind that list of beautiful blandishments - "early dusk, utter darkness...harvest evening, abandoned orchard...white birch blown bare..." and the journey through Thomson's work. Thomson's 'Northern River' - which I believed, until this very morning, when I looked it up, to be a painting of a forest fire - hung in my Grade four classroom, probably causing a lifelong 'thing' with northern landscapes. The reviewer makes a convincing case for Deahl's poems confronting the Canadian canvas with as much passion and engagement as Thomson did. "To enter this land is to open the door to another life." Ask your local bookseller for a passport.