Halyna Kruk’s A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails (and Four Other Griffin 2024 Titles)

A Michael Greenstein Review

Halyna Kruk’s A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails has been translated from the Ukrainian by Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk. Through moving stanzas, careful punctuation, and poignant imagery she bears witness to the war in Ukraine in “there and back again.” Strong s consonants in the opening stanza ground the poet’s difficult journey: “I travelled there on tranquilizers, / back on painkillers/ there were no other routes.” These routes belong not only to the war-torn landscape, but also to her shattered internal condition where drugs are the necessary accompaniment. “There” is repeated a third time later in the poem, questioning the notion of place and goal amid geographic dislocation— the thereabouts of whereabouts, and the poetic line against the frontline.

The initial s sounds carry on in the second stanza: “i felt so shattered, / feared i’d pierce the aircraft cabin, / the hotel’s interior was so intricately designed, / the interlocutors’ bodies so beautiful.” The verses’ design runs counter to the hotel’s decor. The contrast between beautiful bodies and the war weary appears in the third stanza with its misfits: “war doesn’t suit the rest of the world / like mutilation with an evening gown.” She then spells out the details of that simile: “the look’s too heavy / the language too sharp / the details too brutal.” These are the heavy l’s of tranquilizers, painkillers, and interlocutors, followed by an address to her lover: “let’s close death’s eyes with your hands, dear, / you can reach, you’re closer there.” From close to closer, from there to there, the poet and her lover combine: “we’ve got a special person for the hard conversations / we’ve got a special room / separate entrance and exit, not here, please.” The “not here” positions absence and presence in the urgency of these strangers who witness love and war.

The witness calls on visuals: “death’s turned a blind eye, / but she’s spying “ and “as they see it.” Love provides the only hope: “when you call from the war / birds are chirping / so the world still exists” in its precarious existence. The chirping birds respond to the piercing of aircraft in the fluctuation between there and back again, and prepare for the returning bus in the following poem.

After “PTSD,” the final poem, “be honest with yourself,” concludes with Ukrainian Cyrillic script for “i am we: holes in the ground.” I am is the last letter in the alphabet in the last land where the poet breaks bounds.

Jorie Graham confronts apocalyptic moments in “To 2040,” which begins with “Are We // extinct yet” — a question of identity for individuals, community, and society. Questions follow questions, each running across lines where sentences end mid-line, after enjambment moves maps and stanzas, shifting rhythms of insistence and urgency. “Who owns / the map. May I / look. Where is my / claim. Is my history // verifiable.” The oscillation between singular and plural pronouns, and the stamp of monosyllables until the polysyllabic “verifiable” demand empirical and poetic truth for the witness of history.

She turns to animals to share history and memory, and wonders if they are still here, before wondering if we are all alone. She strives for connective tissues throughout the poem so that “are we” is also our we, the collaboration of various entities between reader and poet. The initial question “may I look” turns to the imperative “Look / the filaments / appear.” Strands and filaments recur in the stanzas that follow, as she questions land: “Did it move through us,” in a crossover where we moved through the land in a migratory pattern of the poem’s motion. “Something says nonstop / are you here”: enjambment enacts the nonstop, while “here” returns to “Are they / still here,” which doubles doubts about hearing as aural witness.

Her interrogation of identity continues through ancestry, body, and “do you have / yr self” where disintegration commences through contractions of “yr” to self and hands. Filaments reappear as thread — “have you broken it / the thread.” Graham attempts to repair threat and thread: “try to feel the / pull of the other / end” in a tug of dialogue— both ends are / alive when u pull to / try to re-enter / here.” Shunting and shuttling along lines, filaments, and threads, she contracts pronouns to answer her earlier questions about “here.”

All of a sudden a raven appears in the eighth stanza, flying into meaning and creation: “A raven // has arrived while I / am taking all this down.” The poet deconstructs the world, and after that apocalyptic taking she also notes the bird through language. The raven “In- / corporates me it // squawks.” Against the corporate world and the poet’s gawk, the raven sounds its squawk and enters into communal dialogue: “he is tapping the stone / all over with his beak.” If the world is almost all over, then the black bird with his coat of sun offers a ray of hope. “He looks / carefully at me bc / I am so still & // eager.” The poet contracts her “because” and ampersand in her loneliness. She asks if this is a real encounter in keeping with the earlier question concerning ancestral reality.

“Here” reappears in the words of the light: “You / are barely here,” followed by the “raven left a // long time ago.” Thread also reappears to connect parts of the poem and the raven’s flight pattern: “It / is traveling its thread its / skyroad forever now.” Just as the bird has its own path, so the poet looks at her metapoetic direction: “But is it not / here I ask looking up // through my stanzas.” All the asking fluctuates from the final sentence back to the earlier thread of narrative path: “Did / it not enter here // at stanza eight.” Here is any place in the poem from line to line and stanza to stanza. The poem reaches a finishing line in a flight of ampersands and the exit of the golden raven. The burnished raven flies phoenix to 2040.

Ishion Hutchinson’s School of Instructions begins with Selections from “His Idylls at Happy Grove.” From his Jamaican perch the poet revisits history: “Agog with corrosive dates in his book, / Godspeed shuttled between bush and school, / branching with delirium.” Like other “sh” sounds in the poem, this shuttle is fraught between nature and schools of instruction, while “Agog” branches with the apocalyptic Gog and Magog later in the poem. The post-traumatic poet branches corrosive cannons, delirious dates, and escutcheons that “fluttered a red-letter day of sorrow.” On the bloody banners of battle: “Every man who went from Jamaica to/ the front was a volunteer. 10,000.”

Every man from World War I turns to Everyman. The poet queries the official version of history: “Volunteer? Bourrage de crane. Shadowed chains.” Brainwashing propaganda begins with volunteers, but ends with shedding light on history’s shadows. Conditions aboard the ship Verdala: “white flashes of sharks / haunting fevers strangers shared in the hulls, / never to break after centuries on land; / perpetual flashes, perpetual sharks.” This reversed, belated Middle Passage is a double crossing of cranial hauntology, to be uncovered and recovered during and after the blizzard of war.

Conditions on land are just as vicious as at sea: “They shovelled the long trenches day and night.” The trauma of mud stomped onto history in a litany of lists, the bogging down of World War I: “Frostbitten mud. Shellshock mud. Dungheap mud. Imperial mud.” Every type of mud imaginable that sucks the elements down in history’s miasma. “No-man’s-land’s — Everyman’s mud” includes “Gog mud. Magog mud.” Until the final couplet: “They resurrected new counterkingdoms, / by the arbitrament of the sword mud.” Hutchinson wields his mightier pen in counter-versing and recovering official histories.

Ann Lauterbach’s “Door” is a meditation in eleven sections, constructed and deconstructed through pentameter couplets. Lacking an article, door becomes partly verbal: if floor may be floored, then Lauterbach doors experience dramatically and abstractly. Furthermore, if her monosyllable divides into do and or, we are thrust into action and choice, as she parses object and experience. “The Said closes, is closing, has closed the door. / John said, I am the door. Who closed it”? The Said opens the dialogue of Door, with John intervening between the two. Once animated, the door closes itself until the next stanza opens it: “And who will open it, if it is not shut / forever? This is the other question.” The door metaphor hinges openings and closings, entrances and exits to and from meaning between the lines.

If John’s identity is called into question, so too is that of the young Marine in uniform who calls from the balcony in a staged setting that revolves around the door, spreading to “the entire arena.” Matches flame to light and flicker the arena with its own memory. The self-reflexive stage asks “Who is there?” Surrounding the personified door are lights, knocks, hands, faces, crowds, and surges. “The street flares again / in the mind’s geography.” The parade continues to expand, “cascading out from the numerical / so everyone is passing, countless.” Abstract expressionism surrounds the door’s identity: “Anonymity caresses its dream / and you were there, inside me, // where no story can be told, but for / the passivity of the mute child.” Dream and story condense from noisy crowds to individual, the surge of activity to the passive, mute child inside door, room, body, identity.

Her long sequence concludes with the titular phoneme and morpheme that has morphed through lines of leaping thought: “How to name a sound? Call it Door. / I know what comes next; I remember this tune.” It is the wound of sound and the sound of wound.

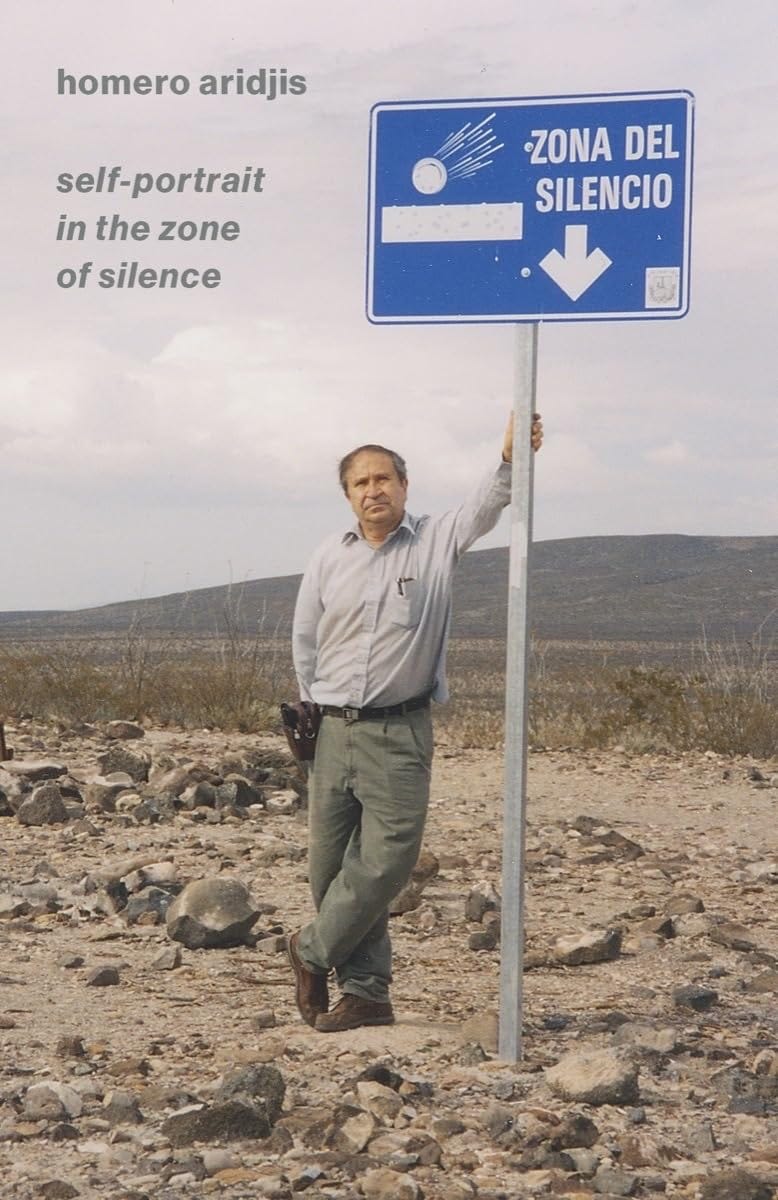

Canadian poet George McWhirter won the Griffin Prize for his translation of Mexican poet Homero Aridjis. Aridjis’s Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence probes his solitary condition. In “Meeting with My Father in the Orchard” the poet sees his father who is alone since the death of the poet’s mother. After their encounter, “Then, each went on his own way” past “tall sorrowful walls / on the point of coming down.” Loneliness returns at the end of “The Sacrificial Stone”: “soon I will be the god who slaughters me.” Similarly, “The Sun of the Blind” falls on vacancy: “That evening six-o’clock sun / setting like a sob / between the buildings,” and “That vagabond sun / that is taking a seat / on the vacant barbers’ chairs.” The mundane and quotidian zone of silence reappears in “Garden of Ghosts”: “All are gone” and “you alone, my invisible mother, are here.” Even in the more upbeat stanzas of “The Creation of the World by the Animals” the birds began dancing a solo of light.”

That solo of light turns darker in the titular “Self-Portrait in the Zone of Silence.” The self-reflexive mirror is tragicomic: “On the wall of the room there was a mirror / reflecting back a comical skull that was laughing at itself. / Jawbones knit together by the threads of death.” Once again, the proximity of thread and threat in the dread of death, as the mirrors multiply towards a mise en abyme: “Behind there was yet another and another.” This self-portrait in a smoking mirror is both solitary and manifold, zoning a voiceless laugh between jaws and claws, close-by and afar. “A black mirror reflected my solitary person.” Yet that solitary person is complicated by “duality’s silhouette “ and a door that opens onto the infinite. Through labyrinths and jawbones the poet comes face to face with himself, as a mise en abyme takes over: “and in the vertigo of my-self I was alone with my mind.” A dog with a human face watches him “as if I were its alter-ego.” Amidst Mexico’s double pyramid Aridjis lives in a state of poetry, now neighboured by the Griffin.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.