Metromorphoses by John Reibetanz

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Ring Cycles

Unpack John Reibetanz’s portmanteau “Metromorphoses,” and you might find alongside Ovidian metamorphoses, Ezra Pound’s metro station – apparition, wet petals, black bough. (Earlier, “The Hammer” echoes “and pound and pound.”) From his earlier collection, Transformations, one would expect additional forms of transformation in his latest collection of urban and urbane poetry, Metromorphoses. In his variegated Toronto settings, sounds and sights metamorphose carefully. “Shall We Gather at the River?” poses the question of onomatopoeia where “gather” rhymes with river while enacting its own force of acoustic accumulation and history of harvesting. Compact tercets course through the poem without punctuation to imitate the flow of river and civilization in one sentence. After the title’s future tense, the rest of the poem probes the past in a surge of geology, archaeology, and anthropology.

The personal pronoun in the title shifts to the third person to gather past and present, others and ourselves:

“They did for eleven thousand years

each generation portaging then

gliding on sky-mirroring current”

“Then” is a fulcrum pointing backwards to prehistoric times before moving on in the next line’s sequence and motion. Gliding gathers generations over centuries, caught in the ensnarement of n sounds: eleven, thousand, generation, portaging, then, gliding, on, mirroring, and current. Tethered tercets and flowing tetrameters perform the pulse and ring of this verse.

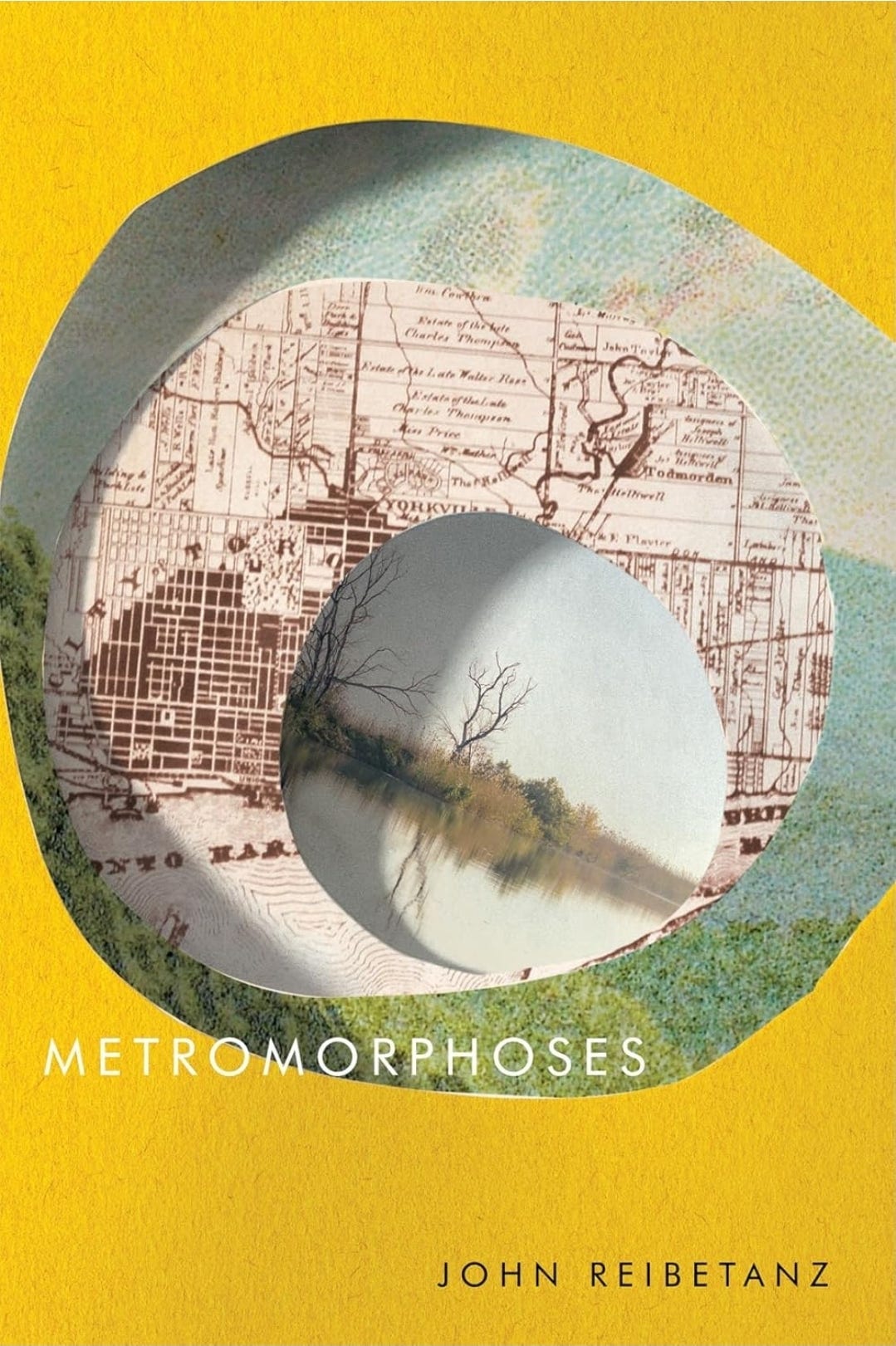

Reibetanz’s mimetic current flows and portages into the next stanza in the mouth of human, salmon, river: “In the mouth of the river that in / fall was riveted with the gleaming / armour of salmon gathering for.” Although the suffix of present participles is dominant in this poem of ongoings, the particular ending of “gathering” signals a ring formation of circle, sound, and substance. From circles on the book’s cover to cycles in stanzas, the poet rivets his river around city and surge of currents. The solidity of riveted armour anchors the flow of “upstream homecomings when the river / bore a more muted burden of leaves / past smaller winter settlements.” Part of a broader cycle, the change of seasons is concentrated in alliteration of bore and burden, bracketing “more muted,” which itself carries the internal rhyme of bore and more where “bore” not only carries a burden, but also bores into the riveted armour of togetherness. Where Wordsworth comes upon a leech gatherer, Reibetanz gathers a leeching earth.

His river is a bearer of leaves, lines of stanza, landscape and language – its source a birth, its mouth a burial:

burial sites the banks gathering

them and their prized possession a pipe

at one through which a current of smoke

Alliterations gather along tetrameters from burial banks to prized possession pipe. These burial sites look backward to birth and foreword to “birthing” in the next tercet, as the poet carves artifacts, shaped lines and waters:

once flowed its bowl carved in the figure

of a pregnant woman her body

birthing fragrance and at another

Flowed bowl opens birth-like, only to be enclosed in heavier r sounds in carved, figure, pregnant, her, birthing, fragrance, and another.

Stanzas exhibit a morphing in found objects of ritual and mythic sedimentation:

a comb over whose teeth a horned snake

glides and forms the tail of the panther

Mishipizhew from whose head rises

The possessive “whose” takes over to underline the multiple creaturely metamorphoses from snake to panther, and bear, the teeth on the comb turning to the bite of panther. From gliding in the opening stanza, we land on the snake’s glide and Ojibway lynx. A rising and falling pattern of currents and history appears in the penultimate stanza, which circles through the poem, its sibilants suggesting mists:

a bear whose bent torso waterfalls

into a human sitting astride

the panther the same current of life

The same current identifies life, snake, and smoke in a cycle of waterfalls, which rise in the final tercet of eternal recurrence, a confluence of streams, stones, and stanzas:

charging through their veins like a river

emptying into the sea where mists

gather and rise and return as rain.

Stanzas echo not only within an individual poem, but also between poems as “Don River Lingo” picks up where “Shall We Gather at the River?” leaves off.

The flow of water and the flow of words

for them were one the waterway a speech-

way both picking up images of sky

In the twist of linguistics and Indigenous identity, the poet gathers his river through the balanced alliteration in the first line and the portage of “way” into the third whose “images of sky” mirror the third line of the first poem, “gliding on sky-mirroring current” – mirrors within mirrors in Metromorphoses. Similarly, “were one” returns to the earlier “at one through which a current” of words unifies multiplicity and at-onement of way and word.

Reibetanz’s speech-way continues in the next stanza where a slur of “er” sounds arrest tongue and streambed across littoral lingo:

or bird on surfaces while from within

where currents chirruped over the streambed

and gutturals glided across the tongue

Again, a gathering of sounds binds birds to water to speech in the river’s rhythm –

songnotes of wren or warbler rose to fill

the curvatures of riverbank or ear

verbs coming first in wing-spun sentences

This spin of ring cycles listens to Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “gathers to a greatness” and Robert Frost’s oven bird, while returning to the mists and waterfalls of the first poem:

the way an eager round of water shoots

pure energy out past the waterfall’s

stone rim into an air thickened to mist

Eager and water rhyme around “round,” while mist pivots to history as the lingo-er prepares to return to interactions between settlers and Indigenous myths and history.

Mist thickens into the next stanza’s oneiric self-reflection with its lull of short i’s bracketing long o’s of pouring discourse:

the mist an image of the nebulous

dreamworld where spirits pour discourse into

ears asleep to the noise that thinks itself

Between source and mouth of river and language, a modulation of whisper and noise, silence and a brazen heralding of clashes in the War of 1812:

the only source of life’s upwelling voice

as when the loud retort of strangers’ guns

replaced the arrow’s whispers and a land

A gathering of source and voice leads to the epic simile with further sibilance and a flood of transformations in the rest of the poem

figured as rivering footsteps hardened

into holdings where Pahoombwawindung

named after the approaching roaring thunder

The ring in and of “rivering” and soaring enters the battle with Thomas Smith and William Jackson sounding against Naningahseya and Wonscoteonoch.

The penultimate tercet is a triad anchored between person and place, the footed and rooted to the Don’s Anishinaabe name Wonscoteonoch. History’s tripod surveys the Don River and concludes with Elizabeth Simcoe’s “sympathetic / pale ear” in colonial Ontario, an ear ring that picks up earlier “ear / verbs” and “ears asleep.” Reibetanz presses his ear to earth, history, geography, and other subjects and disciplines. In his sightings and soundings, what is sound is found.

He applies his tripod of resonance to “Unknown Earth,” which features Joseph Bouchette surveying Toronto in 1793. Surveying is webwork, grid and palimpsest of ring cycling:

Nobody knew it lived there just beneath

our feet a webwork of pathways that mocked

the sterile straightness of old Roman roads

This webwork of alliterated n’s, s’s, and r’s proceeds to “a looping crisscross up-down in and out” of “frail-rooted tundra blooms.” Routed around language, the networks “of microscopic caves are mapped” in an effort to protect and preserve them by scientists and geographers. “Nobody” that begins and ends the poem inhabits “terra incognita,” imagination’s unknown place of “deep-shelved carbon” dating millennia before “telescopic tools replaced those of stone.” With his own tripod, the poet protects the pathmakers from oblivion in a confluence of streams, stones, and tethered stanzas.

The poet as potter of civilization appears in “Patterns in Our Clay,” with circles replacing tripod back to eleven thousand years ago, Golden Age and Common Era timed against the human experience of father and child.

He returns to tercets in “Shards and Ashes,” with its retrieval of sightings and soundings:

clunk goes the archaeologist’s

trowel on Local Evening News

through loam poking worked bone worked shell

Onomatopoeia of “clunk” gets echoed in trowel and local before spreading through loam, bone, and shell (that labyrinth of sound). “Worked” underscores transformations through time and effort, while shard and shell labyrinth the labour: “worked antler till the sought-for clink / of shard dates this burial site / near the displaced mouth of the Don.” Metromorphoses mines displacements of person, place, and history – the quest from clunk to clink “to one thousand B.C.E when / the art of firing pottery / first took hold in Ontario.” Poetry takes hold of moments and millennia, time’s verge where “some” becomes the sum and summary of parts: “some shards bear ribbed cubes that some hand / pressed into wet clay with stone tools / some zigzag etched with a tool’s edge.” This zigzag is visual, aural, and a patterning process that works in tandem with the finished product. Poet and potter handwork the “flame-zigzags” across generations, a sublimation from solids to smoke, the sounds of ash, shard, flesh, bush, and nourished lining the legend. The poem ends without any punctuation because of its cyclical nature, its “circles of gift,” zigzags, and displacement of fireweed and river.

The final poem in this section, “Species Song,” sings of history, Toronto’s transformations, and the gathering of music. “When he first hiked the Don Valley trails / all he heard was river as he strode / beside its glitter of smashing glass.” Hiked alliterates with heard, river and glitter rhyme, while “smashing glass” cracks the stanza open to other sounds: “That and the wind which sieved a thin tune / through pine needles near the crest and coaxed / applause from aspen leaves farther down.” “Through” is a key preposition for transformation, as the adamic poet names nature in the music of hemispheres. The narrowed note of short i’s widens in the longer vowels and alliterations in the second line. Farther down refers not only to a position downstream, but also to the evolutionary scale of species and archaeology of civilization – the leaves of what is left behind, and the trope of written leaves.

Time in the next stanza is historical and musical, while wind is inspirational: “but in time wind lifted waves of sound / from sources neither flowing nor fixed / as bitterns mimicked thunder’s bass drum.” Short i’s and d’s in “wind lifted” imitate the action, while tethered tercets and flowing meter further reinforce the verses’ activity and motion. These in turn launch a martial bird song: “redpolls reloaded and then discharged / their miniature pistols of song / and larks rose on rising trill-ladders.” In this species of sound Vaughan Williams’s “Larks Ascending” accompanies Romantic skylarks flying back to Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn at the end of the poem as everyday sound turns symphonic. Nature’s vernacular transforms into spectacular transcendence on Reibetanz’s trill-ladder and bird gatherer, the quotidian sharing the page with the hidden quotation.

After sunset crickets keep warm, “flicking steel sticks across steel pickets / drawing reed-notes from wakened bat throats.” To any pictorial drawing, the wing of bred and bat sounds across stanzas, “and making him wonder what he had / to give in return what change of breath / to music might carry not only.” An exchange in the correspondent breeze between poet and nature, turn and tern, links individual to species: “a lone voice but send his species song / reverberating like the others / through the valley the way a few boughs.” In this vocal company of Pound’s black bough, “species song” echoes belatedly through the early valley of lyric poetry. Apple wood and woodshed call on Robert Frost and a whistling, “which was near kin to their wordless notes.” Those notes and apparitions rise and fall in the final stanza’s gathering:

and like them would ride soundwaves over

the densest undergrowth he whistled

Beethoven up steep slopes and Mozart

ambling down Haydn on tableland

and became known as Symphony Pete

his pursed lips pouring out the shared life

Up and down musical scales, Symphony Pete also whistles his song into “Music at the Mechanics’ Institute” with its wit and witnessing, its synthesis of the everyday and the extraordinary, mundane and sublime, the lightness in gravitas. Under the influence of John Ruskin’s Fors Clavigera, the poem begins and ends on a synaesthetic note blending harmony and history: “The music you hear when you look at / the photo is silent like the sort / that runs through the heads of bowler- / hatted mustachioed men standing.” The observer listens to photography’s silent music that courses from bowler-browed workers to highbrowed “frescoed Muses” in the domed ceiling. The verb “converted” sustains the transformation from Mechanics’ Institute to public library. Architectural and functional conversion in the first half of the poem turns to a different form in the second:

Frescoed Muses in the domed ceiling

nod their approval understanding

the magic of converting black marks

on white leaf-like pages into songs

In this stanza’s music, hard c’s alternate with “a” sounds to fix the fresco before transforming it into motion with liquid l’s in listening and liberating:

they hear when listening in on those

liberated minds vowel breath-winds

and consonantal clusters of leaves

reverberating through their green grove

Reibetanz’s careful alphabet reverberates in the last stanza where photograph is almost interchangeable with phonograph:

even though the ceiling and building

have long disappeared with the readers

who like us heard the song of the past

like the music of a photograph.

All of the quatrains and tetrameters of 4/4 time signature assure us that the music is never mechanical, but rather gathered in the embrace of green, white, and black leaves with their elegiac rustle and clustering.

The eponymous poem, “Metromorphoses,” captures Toronto’s transformations in five sestets. “Bernini caught the moment when Daphne / sprinted from womanhood to treehood.” In this timely neighbourhood the poet transforms the moment of metamorphosis from Ovid to Bernini; he reworks the myth from Hellenistic origins to Renaissance sculpture:

her toes groping for roots her fingers leaves

but his stonework could never have contained

a second alteration if she tired

of twiggy life and sought some nimbler pose

The history of civilization shifts from Rome to Toronto in the second stanza’s alteration of metropolitan motion:

the way this city’s streetscapes cast off guise

after guise innyard into church into

condo theatre to bookshop to drugstore

the moment of transformation stretching

to years or decades less fit for sculpting

than for the time-lapse photographer’s art

The poet’s throughway: a profusion of sibilants, casting language and clay masks, the time-lapse of guises coming after guises, moments to monuments.

Follow the photographer:

If he could fix his lens on Twenty-Nine

Centre Avenue and watch the wood-frame

cottages fall as the two-storey brick

Standard Foundry Company rises to

become the Shaarei Tzedec Synagogue

whose leaded-glass and Stars of David give

Before and after the Depression of 1929, amidst the fixed and repaired frame, cottages fall and a company rises to a synagogue with its gates of justice (Shaarei Tzedec), glass, and Stars.

The way of the fourth stanza returns to the way of the second, as synagogue is transformed to furniture store and parking lot, then to provincial courthouse, a secular gate of justice. All of the buildings’ glass façades play off against the photographer’s miniature lens framing these archival scenes. The poem concludes with the art of civil engineers and elegies “giving our lives the slow timescale of whales / whose hearts beat twice a minute when they dive / and stretch their moments out to centuries.” In time lapses, heart beats, Daphne’s woodwork and nimbler pose, “Metromorphoses” carries us through cities, centuries, and stanzas on the backs of various beats. Reibetanz’s time lapse and multiple exposures weave riverbank and imagination, a city’s palimpsest, metamorphic moods, and circling rhythm.

About the Author

John Reibetanz is an award-winning poet and fellow of Victoria College, Toronto, and senior fellow at Massey College. His most recent collection is New Songs for Orpheus.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Part of the Hugh MacLennan Poetry Series (number 84 in series)

120 Pages, 5 x 7.5

ISBN 9780228020912

May 2024

Formats: Paperback, eBook