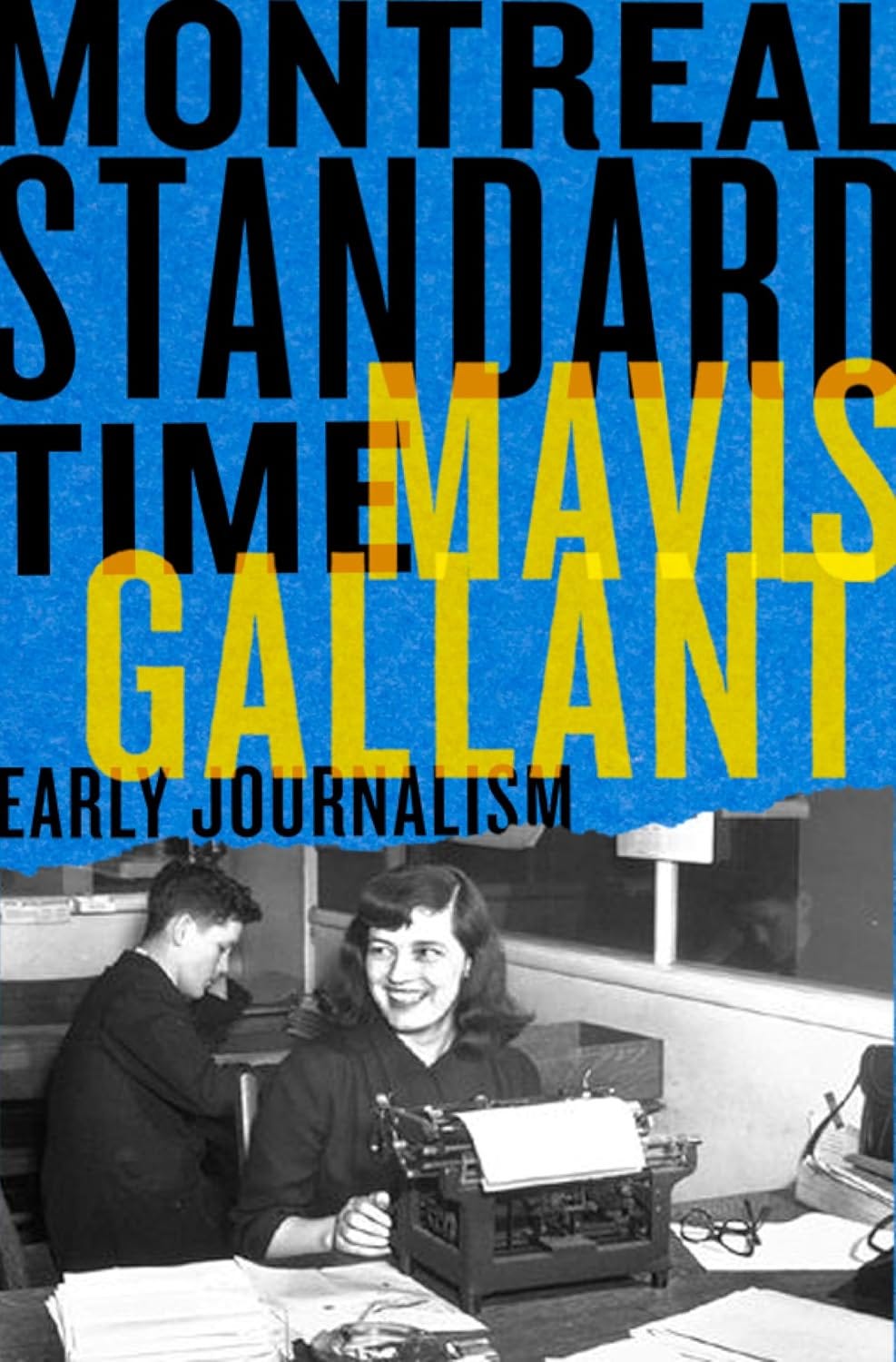

Montreal Standard Time: The Early Journalism of Mavis Gallant

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Like Charles Dickens or Ernest Hemingway, Mavis Gallant began her writing career in journalism before turning to fiction. Her apprenticeship of reporting for the Montreal Standard begins with “Meet Johny” (September 2, 1944) and ends with the story of Johny Young (October 7, 1950). Although these two Johnys are different people, the bookended characters have some resemblances.

The first Johny is tow-headed and wise beyond his years. “Johny is something more than a little tow-head,” and Gallant goes on to fill in the photograph in her crystalline prose. “Aggressive, sharp with wisdom of the streets, he is a personality adjusted to the complicated pattern of city living.” This second sentence builds upon the first, getting inside the tow-head to uncover the child’s street-smarts, and outside to the complexity of Montreal’s streets. At the age of six, he simplifies urban complexities with his two major goals – acquiring nickels and subduing all forces within his reach. It’s almost as if young Johny apprentices to become Johny Young, the gangster in Montreal’s east end.

Gallant navigates the city streets along with her characters. “City streets do not breed gentle children, and Johny loves to fight.” Both Johnys accept the discipline of the gang, while Gallant imposes her own discipline in a prose style that is acutely attentive to detail. From her own early writing she demonstrates a precision in delineation of adjectival tripling that balances her portraiture: “A product of city living, he is cagey, acquisitive, very knowing.” She concludes her column with an allusion to Tom Sawyer, which travels beyond Montreal to Mark Twain’s tow-head on the Mississippi.

From tow-head to tough guy, a fuller picture of Johny appears in “The Making of a Hoodlum.” She begins with a bird’s-eye view from Montreal’s Jacques Cartier Bridge: “One hot July day more than a year ago, a Vancouver businessman Walter Sillanpaa was enjoying a unique view of Montreal.” From this perspective fact and fiction merge, as he surveys “the passing traffic with impatient interest,” drug trafficking passing alongside any rush hour. From the bridging height the journalist descends to Montreal’s underground world. Johny is arrested many times and eventually serves a life sentence for his repeated criminal offenses. “He was a child in many ways. He delighted in newspaper stories about himself even if they were unflattering.” And the reader also delights in Gallant’s newspaper stories connecting children and adults, outsiders and misfits.

Her interests range far beyond the two Johnys. She covers radio drama and significant Québécois authors from Louis Hémon (Maria Chapdelaine) to Claude-Henri Grignon (Un Homme et Son Péché), Gabrielle Roy, and Roger Lemelin. Her humanity is on display in its coverage of these writers, but also in social causes that include women’s rights, the plight of immigrants, miners, and post-traumatic lives after World War II. Gallant bridges Quebec’s two solitudes and Johnys.

“A Wonderful Country” reveals her empathy towards immigrants, but also her style that appears in her short stories. Her pared-down prose is reminiscent of Hemingway whose journalism also transformed into fiction. “I called him the Hungarian because I couldn’t pronounce his name.” Despite their namelessness and distances, the characters interact. “If he had a name for me, I never heard it. We weren’t what you’d call chummy.” Instead of name calling between characters, we are offered a chumminess in their situation – she a junior assistant in a real estate office, he a Hungarian immigrant in search of a place to rent. “It was early in the war then,” and Gallant creates Montreal’s post-war atmosphere throughout her pieces for the Standard.

There is a vagueness about the loneliness of the two characters whose paths cross: “If it had been any other way, we might have become friends, because we were both so lonely in Montreal.” What exactly is the meaning of the conditional clause, “If it had been any other way”? Is there any other way under the circumstances for the immigrant and reporter to alter their fate? Gallant employs Hemingwayesque parataxis to set the record straight in a resignation to destiny: “he needed a furnished house and I needed a commission, so I never bothered to ask if he liked Canada or anything else. I just waved street maps and leases and talked fast.” The fast talk of real estate has to be slowed down in fiction.

Gallant balances the distance between immigrant and agent: “He didn’t know very much about this side of the world and I was too busy to help him.” During that hot summer the narrator criss-crosses the city “trying to find a Hungarian a house.” The experience of finding a furnished place with a yard and nice room for his little daughter is trying: “I’d like to see him try that these days.” Gallant distinguishes between the beginning and end of WW 2, for “Montreal Standard Time” has double standards as well as a double time frame. She analyzes the nature of their bare dialogue: “Talking to him was like being lost in the bush. You could either sit down and give up, or just keep stumbling ahead, hoping to come to something familiar.” There is exasperation and comedy in their inability to communicate fully. Her similes are sideway glances and escape routes to irony. The owners of the house are “alike as two pink junkets,” and when their glances cross, “it was like two express trains passing at full speed.” Caveat emptor, and lector.

She seems bored with this domestic drudgery: “I just stared at the brown wallpaper and wondered if she wore hairnets to bed and hoover aprons in the morning. It was all beyond me. I couldn’t imagine why she was moving out or he was moving in.” This paragraph progresses from vision to wonder, imagining and knowing – each of the stages in Gallant’s ironic observatory. The rhythm of hairnets and hoover aprons recurs in the moving in and out – a puzzlement of human comedy.

Inspection of the house proceeds to the living room: “We moved past her and plunged at once into a lifeless room so like a convent that I expected to hear a bell or see a plaster saint in one corner.” This plunge slides into simile with “or” joining other coordinates of “and” and “but” to beguile simple sense of a tour through the senses: “You could smell wax and lemon oil and sense a faint layer of dust. But you couldn’t see very much because the air was dark green from years of being strained through window shades.” She continues to build on Dickensian domestic detail. The ugliness is filtered through memory: “I remember out of that clutter of plush and seashells, only one beautiful object: something made of tortoise shell, like a piece of fair freckled skin.” Running counter to the owner’s list of possessions is the narrator’s critical list and discerning lens through the clutter before discovering the tortoise shell. Opposed to the aesthetics of tortoise shell, “one squirrel on swing” – the kitsch of oscillation designed to remain permanently in place.

The narrator further evaluates these possessions, as if they were part of a pawn shop or museum of the mundane: “Not only had she taken the trouble to collect the room’s ugly contents, but she had confirmed their existence by writing them in a list, one under the other. Now she was double-checking their identity by taking us on a tour and pointing out each plaque and doily as if it were a museum piece.” For every list a counter catalogue of irony in “A Wonderful Country.”

On to the kitchen, which is climactic or anti-climactic as the Hungarian discovers an eggbeater. As he beats an egg in a bowl, he exclaims “what a wonderful country.” The egg in the bowl is a microcosm of Montreal, but also of a world beaten during war. Indeed, some of Gallant’s writing may be characterized by wartime trauma recollected in vulnerability.

The Hungarian’s innocence is reflected in his childlike singsong cadence: “BEES are there, BIRDS are there, BUTterflies in the air.” These facts of domestic life are qualified by the capitalized “BUT,” a coordinate of consideration. The narrator echoes the Hungarian’s enthusiasm: “His enthusiasm was wonderful,” and the descriptive lists that follow reveal Gallant’s wry, sardonic technique. And yet, her sympathies lie with the Hungarian rather than the smug couple. Her overview almost disappears down the drain: “Nowhere else was there debris of living, or any explanation for the couple’s years together.” The observer confesses her error, as she realizes that the Hungarian’s fascination with ordinary kitchen implements is genuine. “For the first time, I saw the couple exchange a direct look. They thought he was foreign and ridiculous, and it was in his strangeness that they would find something in common.” A foreign correspondent, Gallant exposes home truths.

But the tale takes another turn when the wife announces that she is going into the hospital with a fifty-fifty chance of recovery (yet another instance of the eggbeater’s resonance). The story works through the tension between emotional crises and the humdrum of everyday objects on display. And these intimacies radiate to the outer world. “I wanted to shake her. It was like my neighbour whose son was killed at sea.” The narrator mediates between kitchen and combat, opting finally to remove herself from the fray: “The interplay was all their own, and I had better leave them to it.” Departing from the property, the Hungarian repeats “a wonderful country,” while Gallant layers the irony with her concluding words: “I have often wondered how long the eggbeater kept him happy.” Gallant’s beat goes on in her impeccable timing in Montreal Standard Time.

Rounding out the volume are fine essays by Neil Besner and Marta Dvorák.

About the Editors

Neil Besner wrote the first PhD on Mavis Gallant’s work in 1983 at UBC and published the first full-length book on Gallant in 1988. He has written or edited books on Alice Munro and Carol Shields and co-edited anthologies of poetry and short fiction for Oxford. His most recent book is Fishing With Tardelli: A Memoir of Family in Time Lost (2022).

Marta Dvorák is professor of Canadian and postcolonial literatures in English at the Sorbonne Nouvelle, former associate editor of The International Journal of Canadian Studies, and editor of Commonwealth Essays and Studies.

Bill Richardson, a longtime admirer of the writing of Mavis Gallant, began writing about her on Substack in 2022. His books include Bachelor Brothers’ Bed & Breakfast, I Saw Three Ships, and After Hamelin, a novel for children. He lives in Vancouver.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Véhicule Press (Oct. 24 2024)

Language : English

Paperback : 350 pages

ISBN-10 : 1550656708

ISBN-13 : 978-1550656701

Lovely - I’ve had this on my reading list. Thank you!