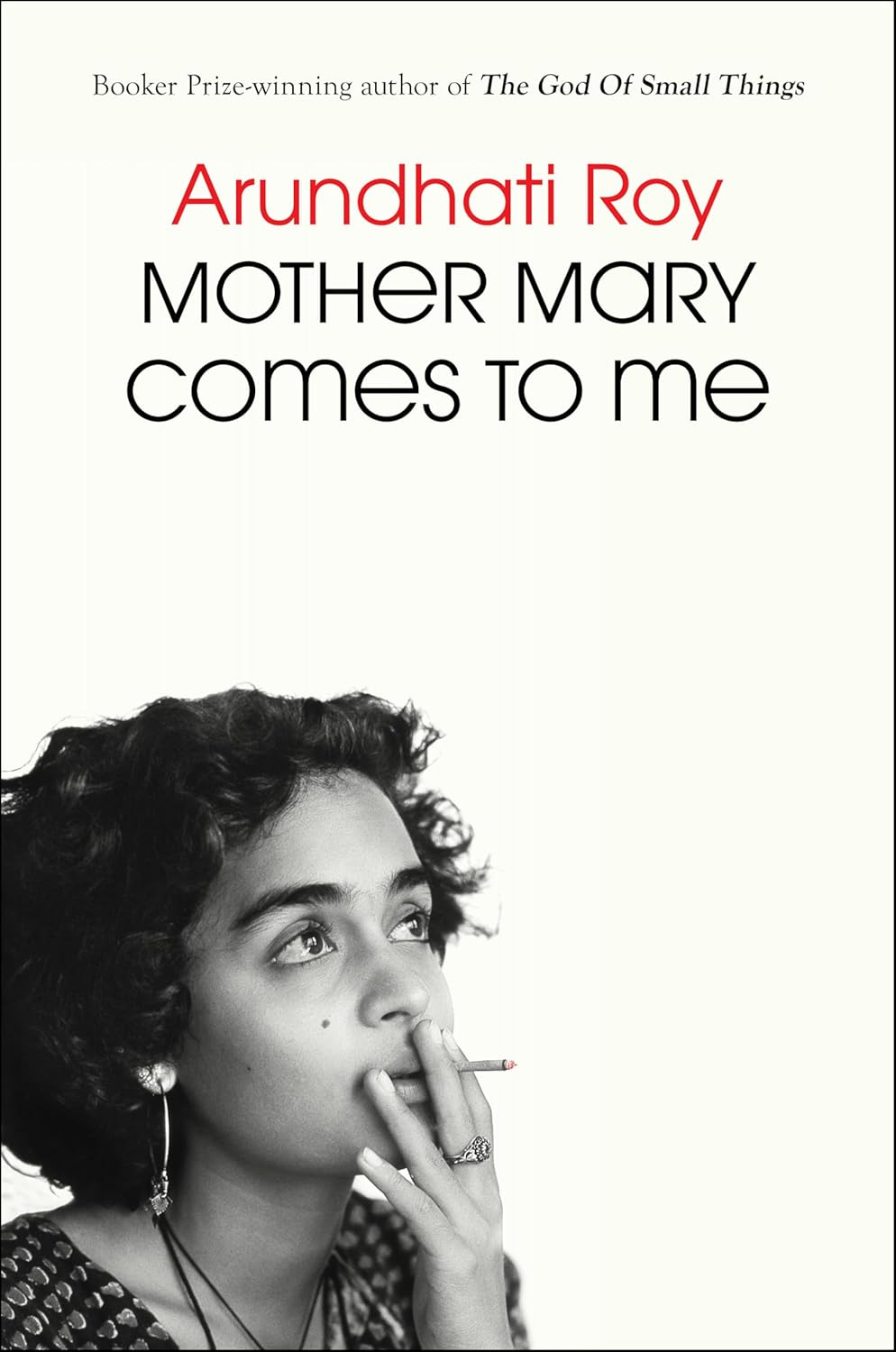

Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Arundhati Roy is best known for her first novel, The God of Small Things, which won the Booker Prize in 1997. Her memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me, once again displays her brilliant writing style and offers autobiographical context for her fiction. If the book’s title is taken from the Beatles’ Let It Be, then the epigraph to her memoir belongs to John Berger: “The guests as they left / kissed the crown of her head / and she knew them / by their voices.” These words may very well apply to Roy’s mother Mary, for the book is largely about Arundhati’s fraught relationship with Mrs. Roy who wears a crown as imposing head of her family as well as the school she has founded in Kerala. The Roy family is part of the Syrian Christian religious community, a minority within sectarian India where clashes between Hindus and Muslims overshadow this largely overlooked religion.

The opening sentence of this memoir demonstrates that it could just as well belong to a novel: “She chose September, that most excellent month, to make her move.” During this superlative month, the move is about her mother’s death at eighty-nine after suffering from asthma for her entire life. Roy advises us to “read this book as you would read a novel.” She confesses that novelists are “labyrinths,” and Mother Mary Comes to Me is filled with mazes, paths of pathos that merge and converge in life and fiction. She mourns her mother: “To bridge the chasm between the legacy of love she left for those whose lives she touched, and the thorns she set down for me, like little floaters in my bloodstream – fishhooks that still catch on soft tissue as my blood makes its way to and from my heart – is why I write this book.” These thorny issues plague the writer’s mind and body.

As if her relationship to her teaching mother were not difficult enough, her absent alcoholic father adds more painful hooks to her and her brother. Her uncle G. Isaac was one of India’s first Rhodes scholars specializing in Greek and Roman mythology. He bequeaths her “the exquisite art of failure.” Roy’s bloodstream is inseparable from the streams of village life in the south of India. “In these strange and manifold ways, this constellation of extraordinary, eccentric, cosmopolitan people, defeated by life, converged on the tiny village of Ayemenem.” She grows up in the death and dying surrounding her asthmatic, charismatic, and overbearing Mrs. Roy: “The shadows that collected in the deep hollows that formed near her collarbones were like a confederation of jeering skulls knocking against one another, their mirthless smiles asking, ‘What will you do now, little girl?’” Like the traumatized child Charles Dickens, she will take up her pen to confront adversity. She also studies architecture to construct resilient forms in psyches and buildings.

Is it any wonder then, that amidst all the familial and political turmoil, she should turn to an attentive John Berger as a surrogate parent or older sibling? “The main attraction for me was that my beloved friend John Berger, one of the most tender, attentive, beautiful writers I have read, was going to be there, too. So many of us had grown up reading his Ways of Seeing.” He sends her a fax: “Your fiction and non-fiction – they walk you around the world like your two legs.” From his village in the French Alps, Berger urges her to complete her second novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, which begins: “She lived in a graveyard like a tree…. Between shifts she conferred with the ghosts of vultures in her high branches. She felt the gentle grip of their talons like an ache in an amputated limb.” Berger listens closely to her magic realm of body and beast, and in another simile encourages her to finish the novel: “I’m standing right behind you like an old elephant, flapping my ears to cool you down.” She calls this old elephant Jumbo, and he calls her Utmost.

Utmost is one of many superlatives that apply in equal measure to Roy’s fiction and this memoir.

About the Author

Arundhati Roy is the author of The God of Small Things, which won the Booker Prize in 1997, and The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, which has been translated into more than forty languages and was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2017. Roy has also published several works of nonfiction including The End of Imagination, The Doctor and the Saint, My Seditious Heart, and Azadi. In 2023, she was awarded the prestigious European Essay Prize for lifetime achievement, and in 2024 the PEN Pinter Prize for telling “urgent stories of injustice with wit and beauty.” She lives in Delhi.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Simon & Schuster Canada

Publication date : Sept. 2 2025

Edition : Canadian

Language : English

Print length : 352 pages

ISBN-10 : 166809505X

ISBN-13 : 978-1668095058