Moving Pictures: The Movers by Noam Gal

Israeli Art in the Third Millennium

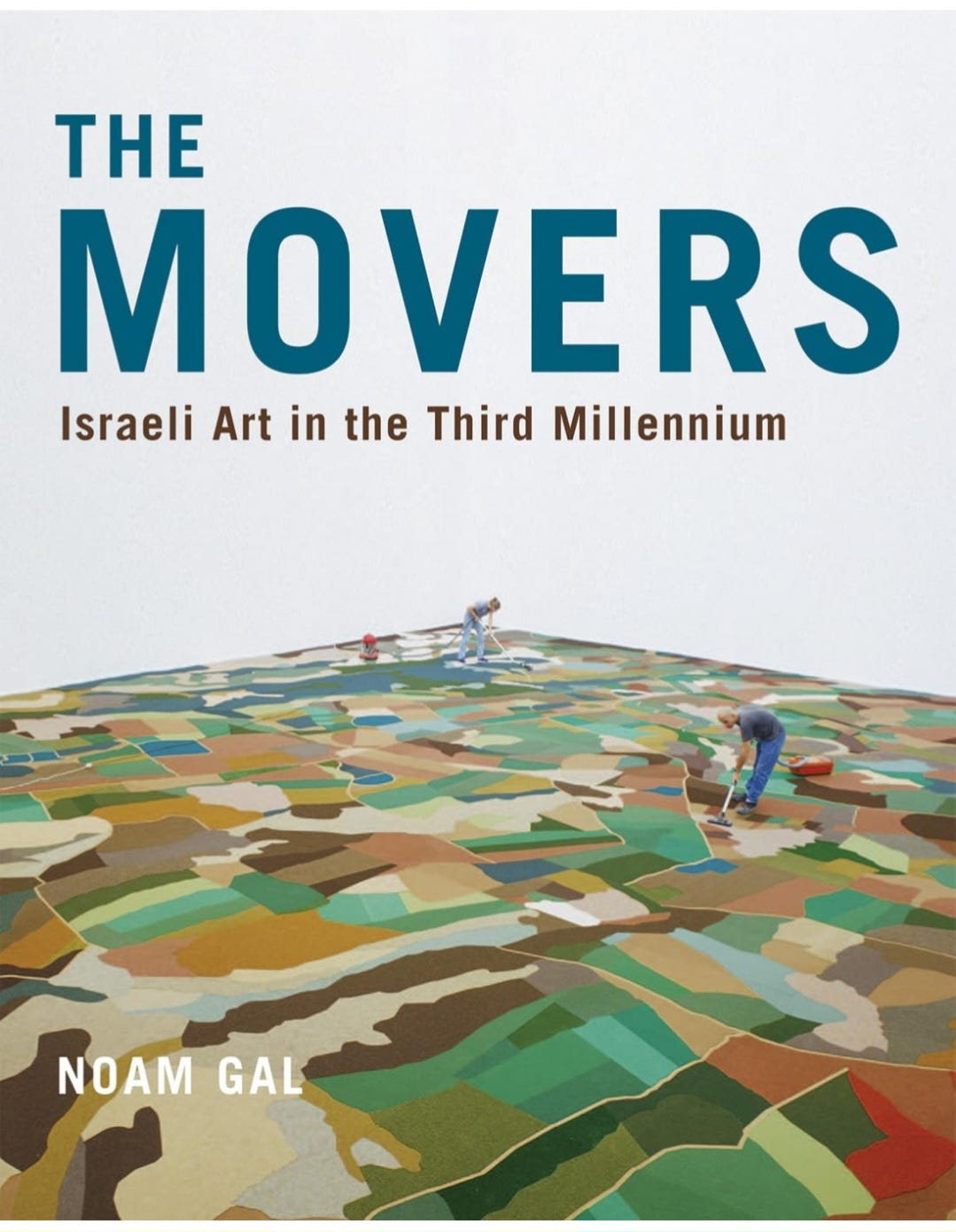

The cover of Noam Gal’s The Movers reproduces Gal Weinstein’s carpet installation, Jezreel Valley. This landscape or “carpetscape” features two stooped workers vacuuming the carpet, painting its synthetic fibres, or sweeping political minefields. Shapes and colours hint at a camouflage of military fatigues in this politically charged region with its archaeological layering from biblical times to a contentious contemporary scene where secular Israeli artists from a variety of backgrounds push back against their right-wing religious government. The two hoovers on the cover move in different directions, cleaning the land from the pollution of a fraught history. The book’s subtitle, “Israeli Art in the Third Millennium,” draws attention to the millennia before the Common Era – hidden centuries beneath the surface of the land.

The book covers six artists, with a number of others featured alongside each one to enrich the discussion. Gal’s “Introduction” sets everything in motion: “Israeli art has never really had a chance to achieve a stable identity” – hence all the movements on different levels. The first work to be examined is Michal Na’aman’s “The Eyes of the Nation,” 1974. Na’aman placed two handmade signs, each with the same phrase, “the eyes of the state,” on Tel Aviv’s beach. The phrase refers to an interview of one of the few surviving soldiers from the battle over Mount Hermon in the Yom Kippur War when soldiers had been left without commanders to fight the Syrian army. The abandoning commander’s comment that “all the eyes of the nation are now looking up to you” was misunderstood to refer to the mountain instead of Israeli society, and this confusion led to the personification of the biblical land as a body with eyes. These ambiguous binoculars focus on trauma and conceptualism – a form of Big Brother is watching, or tragic lifeguards on the beach. This work serves as one template for Gal’s migrating eyes, as he concludes his “Introduction”: “I intend for its readers to consider critically the possibility of further moving the meaning of objects and words (that is, signs), as in moving the meaning of The Eyes of the Nation further so that it denotes neither the vision of soldiers nor that of the mountain, but instead the vision shared among artists and their viewers, there, on the utmost far and fraught frontiers.” Gal’s book impressively shapes those frontiers and vistas.

The first chapter is devoted to “Yael Bartana and the Collective Movement,” another instance of “moving” and the conceptual. In 2011 she represented Poland at the fifty-fourth Venice Biennale with her video trilogy And Europe Will Be Stunned. Across the Mediterranean from Venice protesters marched in Cairo, Tunis, and Tel Aviv, while inside the Polish pavilion Bartana’s films on mirror-like walls reflect the imagined return of three million Jews to Poland. This historic reversal is yet another instance of art moving across time, geography, and genres. Having moved from Israel to Europe, she distances herself from national politics in her allegorical representation of reality. Gal’s commentary deviates from Bartana’s contemporary works to historical considerations in 1928 at Kibbutz Beit Alfa where an archeological excavation uncovered a sixth-century synagogue with its elaborate mosaics. This gave rise to the “masechet” revue or pageant connected to harvest cycles. Gal’s juxtapositions of historical and contemporary events are fascinating and layer his entire text with valuable insights at every turn.

A similar methodology appears in the second chapter, “Gal Weinstein, Cultivating Doubt,” which begins with a 1927 poem written by Rachel Bluwstein about her experience around the Sea of Galilee and Jordan Valley, where she arrived at the age of nineteen as a Zionist pioneer from Kiev. From his analysis of her poem, Gal moves to his consideration of Weinstein’s installation, “Jezreel Valley in the Dark,” also exhibited in the Israeli Pavilion of the 2017 Venice Biennale. He examines the “facts on the ground” of these politically charged installations before turning to the relationship between Zion and nature in A.D. Gordon’s Man and Nature (1927) and Avital Geva’s 1993 installation, “The Greenhouse Project,” as influences on Weinstein. In his shrewd juxtapositions, Gal moves facts, figures, and ground from Israel to the Venice Biennale and beyond.

The third chapter explores realism and alienated labour in the paintings of Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi. Her painting “Shabbat in Jaffa,” 2015 places a dark-skinned man on the threshold of his balcony overlooking the Mediterranean. Gal astutely discusses the situation and the painter’s biography to illuminate the work: “the unexpected minefield under every visualization of identity in today’s Israel, gradually destabilizes the peaceful situation in the painting.” This form of camouflage is further heightened when juxtaposed with another painting in the same gallery, Yosef Zaritsky’s “Tsuba, the Window in the Studio,” which opens up a dialectic between lyrical abstraction and Social Realism – two strains in contemporary Israeli art. Gal takes the discussion one step farther by including Shimon Tzabar’s Shabbat in Jaffa, 1950, before returning to Cherkassky-Nnadi’s oil on canvas, Bamba, which depicts a Russian housekeeper cleaning the floor of an apartment. Her cleaning efforts in turn comment on the carpet cleaners in Weinstein’s Jezreel Valley.

Chapter Four, “Roee Rosen and Bad Reception,” examines his installation Live and Die as Eva Braun (1997) and his depiction of the Holocaust. Included in the discussion are also the artworks of Moshe Gershuni and Hanoch Levin. The chapter concludes with a comment on camouflage: “All along, Rosen keeps his alter egos silent by muting them under the camouflage of intertextuality and hyperliterariness.”

Chapter Five is equally stimulating as it begins with Alexis Granovsky’s 1925 silent film, Jewish Luck. Set in Odessa, this Chaplinesque movie conveys its silent dialogue through Yiddish intertitles where the central character responds to a question about what he is doing with “dawdling around.” In the inn the impoverished characters doodle circles around the rims of their glasses. Menachem Mendel aspires to turning into a matchmaker to secure his fortune and eventually end up in America. Gal highlights the significance of “that very hand movement in the air, that form of turning, circling, moving around.” Gal himself moves deftly from that Yiddish background to the contemporary video of Israeli artist Guy Ben-Ner. En route he treats us to the Canadian documentary film, Nanook of the North (1922). Once again, The Movers moves across centuries, continents, themes, and genres in its ingenious stretches and montage.

In this spirit of circling, the final chapter on the installations of Yehudit Sasportas traces sphere and periphery in her work. First, we discover Paul Celan’s traumatic poem “Todtnauberg” written after he had met with Martin Heidegger on July 25, 1967. The poem opens with circular images: “Arnica, eyebright, the / draft from the well with the / star-die on top.” In her abstract ink drawings “Shichecha” (Oblivion) she responds to the silence between Nazi philosopher and survivor-poet by imagining the German trees as witnesses with voices echoing the encounter. The chapter ends with a discussion of Kabbalistic sphere, as Gal circles his subjects between Israel and the Diaspora in insightful interpretations in McGill-Queen’s publication, an eye-opener in every sense. The Movers engages with postmodern, nomadic migrations that create an unstable identity. The high quality of artistic reproductions on the page goes hand in hand with Gal’s textual commentary.

About the Author

Noam Gal teaches at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published extensively on Victorian, Canadian, and American Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : McGill-Queen’s University Press

Publication date : Dec 16 2025

Language : English

Print length : 192 pages

ISBN-10 : 0228025672

ISBN-13 : 978-0228025672

The carpetscape concept is brilliant - using actual carpet cleaners to visualize clearing away historical/political debris. Weinstein hiding military fatigues patterns in the Jezreel Valley installation adds this whole other layer where the landscape itself becomes a kind of camoflauge. I really dig how Gal traces this thread through so many diferent artists to show how Israeli identity keeps shifting and never quite settles into something stable.