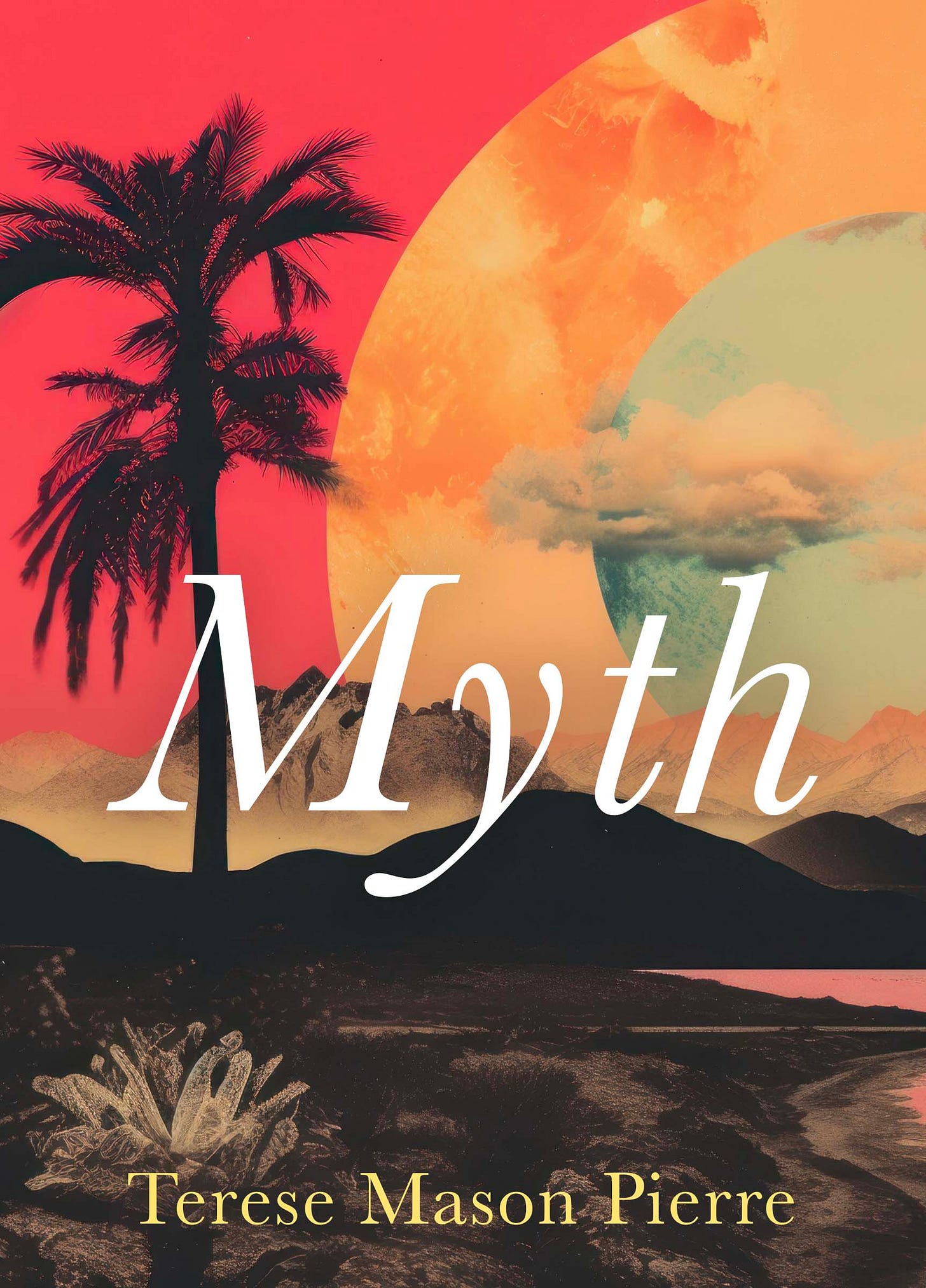

Myth by Terese Mason Pierre

Reviewed by Selena Mercuri

In Myth, Terese Mason Pierre delivers a debut collection that, while speculative, is deeply grounded in emotional and physical reality. The collection shimmers with mythic resonance—not the borrowed grandeur of gods and legends, but the kind that haunts the ordinary: the mythologies of memory, the metaphysics of grief, and the strange poetics of distance. Pierre asks what it means to live in the afterlife of desire and history, and her answer is complex, unruly, and arresting.

“Pierre’s speculative bent—what some might read as surreal or sci-fi—is less of a departure from reality than a return to it from a different angle. In the speculative, Pierre finds a language better suited to grief’s distortions, desire’s intensities, and memory’s refusal to behave.”

The collection opens up a world where longing, rather than being limited to personal ache, encompasses spatial, temporal, and metaphysical elements. In “Grasping Stones,” the speaker confesses:

"I ask the stars: why can't words fail me when I want / them to? I wish I could say I dissolved, but I lingered— / the disrespect. I peered over my own body, saw / my need and eager eyes in the screen. Two oceans away / and not enough to kill the yearning in my throat. / It's always hot when I want something, and I can't / adjust my tongue. Language came so easily to you, / speaking to storms. From a future perch, I can / move through walls and minds like currents, yet I choose / to maintain a boundary. I think about your death / when I want to heave myself into letters, hurricanes / ripping meaning from time, sopping up a blank slate."

Pierre moves beyond capturing yearning across great distances to also depict it across modalities of being—bodily, linguistic, even interdimensional. The speaker is suspended between selves: the watching self, the remembered self, and the imagined future self. The poem is a theory of intimacy, one made from contradiction: hyperconnection through digital screens and an inescapable isolation that stretches “two oceans away.”

Language, throughout the collection, is both refuge and betrayal. Pierre's poems often arrive at the failure of language just as they are demonstrating its power. Her speculative approach doesn’t escape the personal—it intensifies it, charges it with new forms of possibility and risk.

In the title poem, “Myth,” Pierre grounds the speculative in brutal clarity:

"I want a death as real as possible: / old age, a shooting, falling from a cliff, / my maroon frightening the sea. / Ever broad, you'd rather die through myth, / come upon the antagonist of your / mother's disciplines, driving / alone at night, shaking the wrong tree, / sleeping at the opposite end of the bed, / pride matured into an iron noose."

Here, death is simultaneously a bodily certainty and a narrative motif. One speaker longs for a tangible end—age, violence, impact—while another reaches for the mythic, haunted by generational discipline, familial estrangement, and the weight of unspoken pride. Pierre collapses physical, emotional, and symbolic registers into a lyric that skirts the safety of metaphor, insisting instead on a death “as real as possible.”

Still, not all moments in Myth are as forceful. Some of the most affecting lines appear in the quiet, almost incidental poem “Treatment”:

"I don't know how I feel about rain. / It means your call, / a long sign into / the receiver. / You say the rain makes you think / of society and the universe, / how we are all each other / and nothing. / You are purposeful / in your elegy of islands."

The simplicity here belies its depth. Pierre lets the intimacy unfold in fragments—speech across distance, a meditation on universality and isolation, the elegy of islands (archipelagic, diasporic, emotional). The line “we are all each other / and nothing” could stand as a thesis for the collection itself: Myth is invested in that precise paradox of connection and erasure.

The speakers in this collection inhabit their own contradictions. Pierre’s speculative bent—what some might read as surreal or sci-fi—is less of a departure from reality than a return to it from a different angle. In the speculative, Pierre finds a language better suited to grief’s distortions, desire’s intensities, and memory’s refusal to behave.

What distinguishes Myth is not only its formal inventiveness, but its philosophical reach. Pierre is acutely aware of the porous boundaries between interior life and cultural inheritance. Her poems suggest that subjectivity is shaped as much by ancestral memory and imagined futures as by immediate experience. In this sense, Myth is a sustained inquiry into how we come to know ourselves through distance—temporal, emotional, and otherwise.

About the Author

Terese Mason Pierre (she/her) is a writer, poet, and editor whose work has appeared in the Walrus, ROOM, Brick, Quill & Quire, Uncanny, and Year’s Best Canadian Fantasy and Science Fiction. Her work has been nominated for the bpNichol Chapbook Award, Best of the Net, the Aurora Award, the Rhysling Award, and the Ignyte Award. She is one of ten winners of the Writers’ Trust Journey Prize and was named a Writers’ Trust Rising Star. Terese is the chief programming officer at Augur, a speculative arts nonprofit, and co-director of AugurCon, Augur’s biennial speculative arts conference. Terese lives in Toronto.

Book Details

Publisher: House of Anansi

Language: English

Paperback: 120 pages

ISBN-13: 978-1487013042