National Animal by Derek Webster

A Poetry Review by Michael Greenstein

“His subtle animal swims through sounds of person, nation, and cosmic currents.”

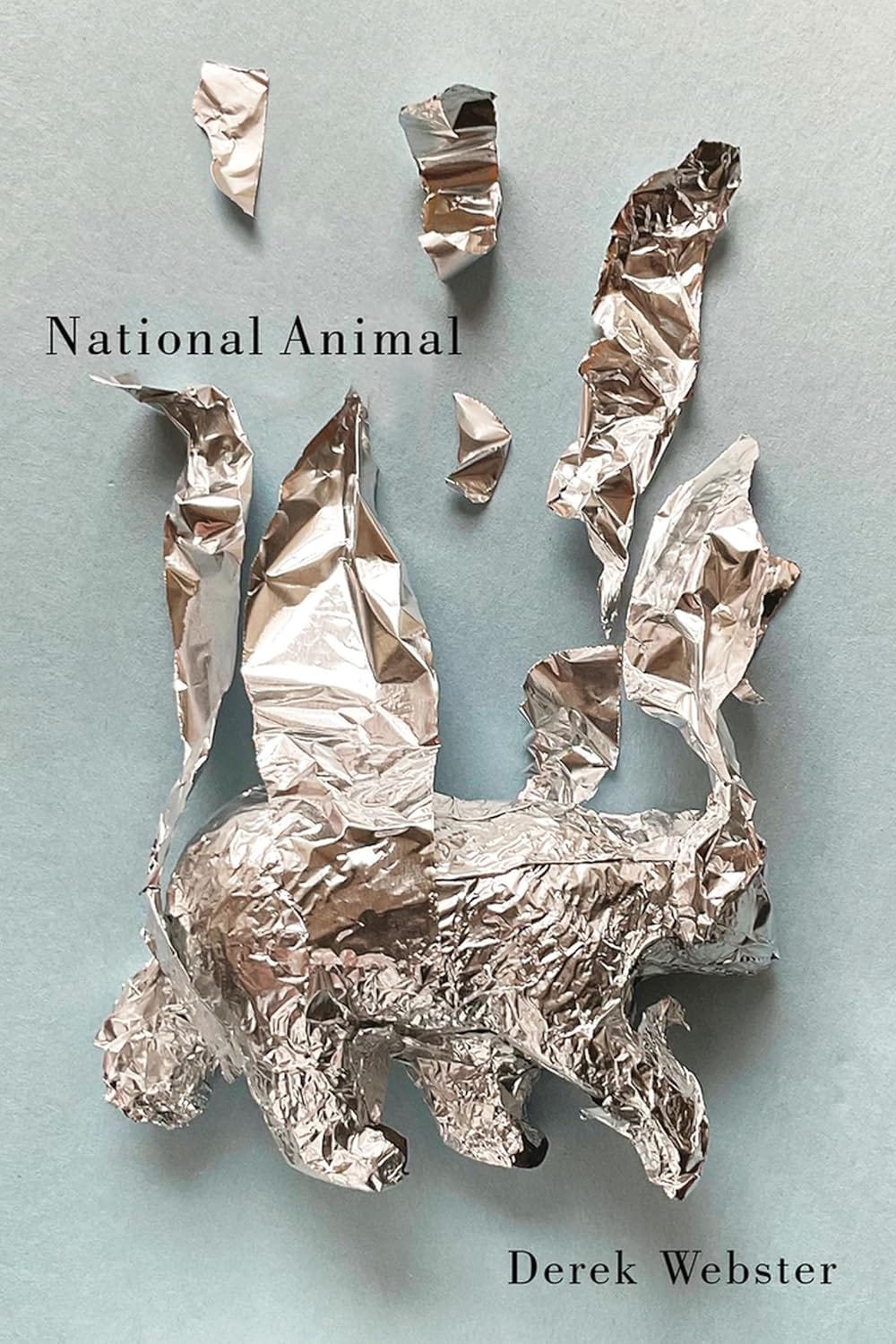

Kudos to David Drummond for his fine design of another coruscating cover for Véhicule Press. Crinkled gold leaf in the shape of Canada and a quadruped – whether beaver or ocelot – shines like shook foil for the poems in National Animal, Derek Webster’s sophomore collection. The eponymous poem, “National Animal,” encapsulates Webster’s soundscape in its rhyme, assonance, and consonance. The first quatrain consists of one sentence, punctuated according to the animal’s movement across imperial silence:

Amid mud-hardened branches, it hates whatever once kept it greasy and warm, its formaldehydean psyche, half-duck, adrift in this foreign home.

Like the braided title, the stanza catches “Amid” between mud and adrift, as Webster’s tetrameters swim between k and m consonants. The strong “hates” picks up “hardened” on the way to another hyphenated “half-duck” and “home,” while the elongated “formaldehydean” alliterates with “foreign” and rings its vowels with “psyche.”

Part beaver, part duck in its oxymoronic foreign home, the Canadian creature advances and retreats in the next stanza:

It chews up the book of what it was – finds on the next page, enraged, its story keeps going.

The enraged page leads to the final stanza, which stretches more than the intermediate stanza and divides into sentences:

This is Jerusalem the crowned lady on the wall smiles. Winter or summer, it trembles, gnawing on itself, surviving on its wiles.

From initial on or on to rhyme of smiles and wiles to alliteration of wall, winter, and wiles, the stanza imitates the animal’s action. Chewing up its book of history and gnawing on itself, the beaver slouches toward Jerusalem.

This wily animal appears in “The Writing on the Wall,” which immediately precedes “National Animal.” Through tercets and tetrameters Webster measures Montreal:

The graffiti eraser in Montreal blasts the red brick wall with water, removing Vive le Québec libre.

The list of this counter discourse carries through the second stanza in cleansing sounds:

Earlier this week he scrubbed off fugg it and baise-moi, stencils of tanks and skulls, a few fat dicks, one whore, sixteen illegible tags.

Cumulative fricatives and sibilants underscore his removal of fading, indelible graffiti. Sprayed sound fills the poem: “a secular silence fills the civic moment. / Slicker open, the man smokes by his van / as toxins leach from the wall.” Webster’s imperial silence echoes against walls that explode into pictures of crowned smiles. The dialectic between sentence and stanza constitutes part of his poetic slant between civic and cosmic truths.

He is also drawn to sonnets, as in the opening “King Canute,” which meshes domestic and monarchic realms, as the speaker enters into dialogue with his father. The first sentence sets the domestic scene within tetrameters where t consonants, short i’s and long a’s introduce the differences between father and son: “We are debating the limits of power / one night late at the kitchen table.” Father tells son about Canute’s soldiers attacking waves, which ended his reign, but the son replies that the crying continued after the wars. Father and king are conflated by the end of the octave: “He looks surprised. I am thirty-one, tired / of the wise king’s lesson. He sighs. / The king was trying to say something.” The repeated “one” suggests the “won” of victory.

In the sestet the limits of power move outward from the initial kitchen: “In the glass door’s reflection, our deaf-mute alternates / swing mythic objects, stabbing / at what they fear in the dark.” The concluding tercet stabs at surrealism in sounds of f and sh, and crows’ “third lids”:

Outside by a gopher’s den, furred shoulders shiver and crows blink their third lids. Under grass water marches, slaughtering the hills.

Furred shoulders reappear in another sonnet, “Portrait with Stuffed Jackalope,” with another animal taxidermied to the wall. A jackalope is a portmanteau of jackrabbit and antelope, but in this poem about predators it also embraces jackals. The opening sentence strikes a note of solemnity: “Something like divine justice afflicts us.” The vagueness of something gets pinned down in the lines that follow in specificity and the interplay of long and short i’s. Ominous justice carries through to “judgement” at the end of the octave and in “just” near the end of the sestet while “like” reappears in “squid-like” plastic bags in this apocalyptic portrait.

“Look at the signs: bushes light themselves ablaze, / icebergs run as lemmings into overcrowded seas, / squid-like plastic bags hang from the branches.” Ecosystems are inverted and reversed:

Remember when the great rivers raced backwards and trees, bodies, houses, hills were driven under? Now the lucky unlucky pierce our perimeter, starving, against their older judgement.

Memory and river look to the past: “remember” is almost a palindrome of reversal and alliterated r’s caught in a swirl. (Indeed, a later poem highlights “do re in remembrance of me.”) The eddy and release of enjambment leads to a punctuated line of caesuras, internal rhyme, and more alliterations that grasp details of the portrait. The paradoxical lucky unlucky points to our afflicted dilemma, while “starving” completes the opening “Something.”

The sestet relies entirely on enjambment for its startling surreal effect: “You used to say It’s not too late before praying / mantises climbed the sugar-water dispenser / and garrotted the hummingbirds.” The play on praying is picked up by the later “predatory,” while the rapidity of hummingbird wings is arrested by garrotted and accumulation of r sounds. The final sentence draws a comparison with Francis Bacon’s portraits “had he been painting / a predatory beauty just coming to life, eating / through the skull of an old, iridescent hope.” Praying, painting, coming, and eating iridesce the hope and despair of hummingbirds and a jackalope stuffed, starving, and eating through the skull.

Webster’s sense of an ending reappears in the penultimate poem, “The Thinker,” whose ten parts are based on Wallace Stevens’ “The Auroras of Autumn.” Brian Greene’s Until the End of Time serves as an epigraph for this long poem, whose sections use dichotomies as titles: “Singularity / Genesis,” “Entropy / Language.” These dichotomies don‘t necessarily represent opposites, but rather different ways of thinking through thought. The first part begins and ends with the same words – “One must be one with it, the universe.” Yet the punctuation shifts towards the end of the two sentences that suggest a closure: “One must be with it. The universe.”

“The Thinker” provides variations on singularity towards a multiplicity, from individual to universal: “Its web of threaded variation making / more threads, multiplying.” The web snags, yet spread continues mathematically and through “River-meander.” Antonymic cleavage recurs through hyphenated “flipped-for” and “fence-like” – in eddying and isolating stories of creation.

Opposites between genesis and endings recur in “Parables of feather and bowling ball / falling as equals – not falling at all.” Biblical beginnings echo through “And / nothing began, and everything. Then light.” The sounds of myth and creation: “the vaunted singularity. / Hammering heat, matter’s hissing sword.” A reference to “Sculpted bonsai” is a reminder of Rodin’s The Thinker, which in turn carves Dante’s universe. The dominance of m’s underscores creatio ex nihilo: mist, making, more, multiplying, mathematics, meander, Mars, matrix, matter, moonlit, and master maker. Thinking, Webster clenches and releases Rodin and Stevens.

The second section, “Entropy / Language,” uses internal rhyme to entrap meaning: “Egg-like, the sun delivers ancient light.” The second line, “Downward the energy flows, each step weaker,” begins a refrain that culminates in “Downward the energy flows, a subtle removal.” That repeats the third line, “a subtle removal of all that is useful,” with its strong internal rhyme heightened by l’s that run through the poem to engage and release entropic flow of language from “long-limbed” to “cross-legged.” Downward motion is accompanied by forward and backward welter within variations of catch and release. “Cyanobacteria capture photons,” while “Flagella spin their seeds.” The poet’s spin steps “first backward to caves,” then “slides forward” to conclude in its questioning of meaning: “A figure cross-legged in a room, hearing / these things starts to dwell on what they mean.” Rodin and the reader ruminate on animal removal of goats and sheep herded into entropic shapes.

Domestic and cosmic dimensions develop in the third section, “Unity / Division,” as room expands to house: “The home, a microclimate of belief / where sounds become ghosts that drag their chains.” In the womb’s silence neurons turn to “neutrons of hate, protons of forgiveness” in Webster’s scientific web of biology and physics. A procession of sounds and images arrive, and “A house rises. A house, abandoned, falls. / Donkeyed in soft blankets, eyes wide beneath / cold stars, the couple with child keep moving, / bereft, alive with suffering and twinness.” The twinness of unity and division informs “The Thinker” from “to move apart” to figures that “unstick themselves.”

Part iv, “War / Difference,” focusses on a tower and ends with “Beyond these walls, through the arrow slits, / bouncing tumbleweeds spin their dry wit.” Webster’s writing on the wall spins story and verse to the next section, “Objects / Distance,” with its cave walls and kitchen clock. The long poem ranges among cosmic, domestic, and mythic elements; archetypal and humdrum houseplants; chained to slope and breaking embrace: “no family’s orbiting agenda, / no balance of power and spinning out.” Each of the subtitles offers a sense of direction for thinking in the poem: “Movement / Contact,” “Multiverse / Possibility,” “Vibration / Song,” and “Galaxies / Dance,” which ends with “spin of any presence.” National Animal spins and shapes sentences, stanzas, and song in thought-filled verse.

The final word of this sequence is “Curtain” – a bow to the dramatic nature of the poem, as well as another wall covering. Webster’s autumnal auroras spin across Stevens, Rodin, and Dante’s Divine Comedy, as they highlight and apprehend thinker, thinking, and thought. His subtle animal swims through sounds of person, nation, and cosmic currents.

About the Author

Derek Webster’s Mockingbird (2015) was a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award for best first book of poems in Canada. He received an MFA from Washington University in St. Louis, where he studied with Carl Phillips, and was the founding editor of Maisonneuve magazine. He lives in Montreal and Toronto.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Signal Editions (April 15 2024)

Language : English

Paperback : 80 pages

ISBN-10 : 1550656570

ISBN-13 : 978-1550656572