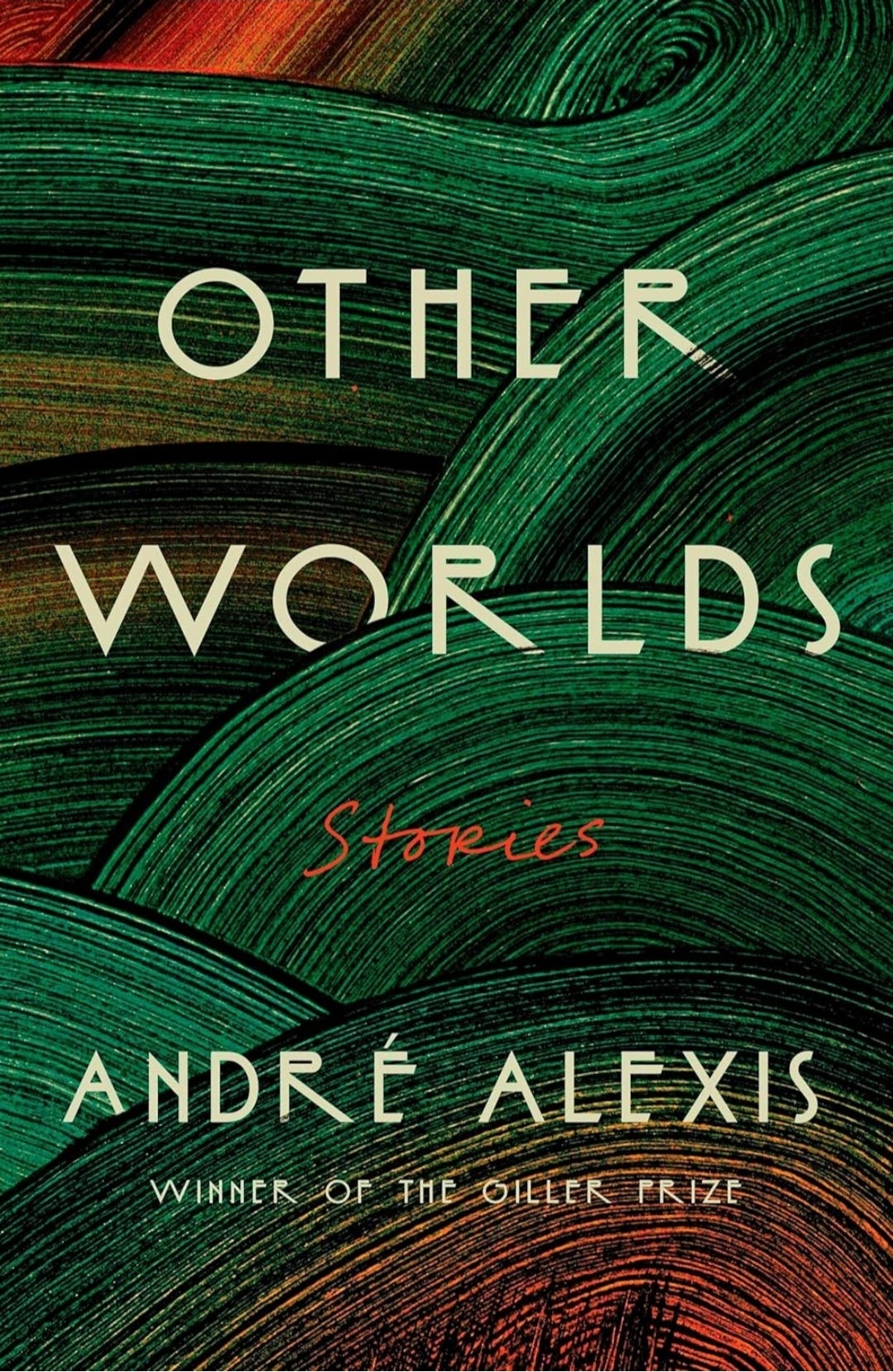

Other Worlds: Stories by André Alexis

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Under Standing

For those readers who prefer some biographical information before plunging into a work of art, it may be advisable to begin André Alexis’s Other Worlds with his last story or essay, “An Elegy,” which offers a meaningful entrée into the aesthetics of his fiction. “An Elegy” is not just a lament for his ancestors and homeland; it is also a blueprint for magical techniques accompanying the questionable realism of the stories. Remembering his earliest experiences in Trinidad, he refers to the “patois” he heard as a child that was not English. “But I understood something of what Gramma Hilda was saying to Gramma Ada. My confusion came from hovering on the verge of understanding without passing through.” Understanding courses through the stories whose characters hover with the reader on edges of understanding their otherness in other words and worlds.

“Understanding courses through the stories whose characters hover with the reader on edges of understanding their otherness in other words and worlds.”

His great-grandmother’s name, Ada Homer, resonates with him sixty years after her death, partly because of the epic role of the Odyssey in his life, and partly because of his relationship to homes, homely, and unhomely. Her language evokes “the shock of being suddenly unable to understand her.” He questions the sounds: “Why couldn’t I understand them?” His incomprehension includes a sense of shame towards language, “as if I were at fault for not understanding.” In Alexis’s elegy and stories concerning human understanding, “I understood that I was an English speaker. I also understood … it might not have been.” On the one hand, the Garifuna of Trinidad; on the other, French immersion at Ecole Garneau in Ottawa. Between an absent ancestral Garifuna and Garneau’s French, English emerges as a keen understanding. His sensitivity to language recurs in nightmares when someone begins to talk to the dreamer: “to my shame, I realize I don’t understand what they are saying.”

In this literary autobiography, writing becomes the psychic equivalent of a search for home. For Alexis, the surprise is “that it took me so long to understand the extent to which I refused to accept home … and became obsessed with the unhomely, with the strange.” This linguistic odyssey examines the German “unheimlich” (uncanny) as well as his nickname “Axle” (black) – both of which account for strangeness in his writing and other worlds. Leaving, isolation, and uncertainty come into play and invoke Kafka, Virginia Woolf, and many other modernists and postmodernists. An alienating displacement calls for some understanding: “when I was taken from Trinidad, when I finally understood that I was trapped in Canada.” His migration also includes a journey in etymology, specifically the French word, “déboussolé.” Before launching on an aside in a parenthetic paragraph, (and Alexis’s asides and parentheses cannot be overlooked), he describes his immigrant self: “It is the self for whom an understanding of symbols, sounds, and language are linked to survival.” That sentence provides one key to unlock Alexis’s fiction where symbols, sounds, and language migrate and metamorphose across the page.

The paragraph in question informs us about compasses and disorientation, but Alexis prefers the French word, “déboussolé,” which derives from “boussole” (compass). To take this instrument one step further, “boussole” itself is derived from a box for medicine, as well as a revolving door. Container plus hinge allow the compass to enact stillness and motion. Without compass or compasses, the author re-creates bewilderment and resentment. His mobile stillness and angled prose perspective recur in each story: “Moving, in work to work, from one genre to the next is almost as important to me as genre itself.” The reader may be caught off guard by the movement from realism to fantasy: one eye is fixed on a stable structure, while the other roams in different directions making sense of shifting worlds.

His wanderings include Kafka, Tolstoy, Joyce, Proust, Beckett, Austen, Kawabata, Queneau, Harry Mathews, Italo Calvino, Henry James, Tommaso Landolfi, Michael Ondaatje, and Witold Gombrowicz – a canon in motion. In a longer aside, he informs us that this essay was written in Hemingway’s favourite café in Paris, the Closerie des Lilas. Like Hemingway, Alexis chooses to write at the bar, “standing up.” Given that standing and understanding are related and connected, the reader may trace these physical, psychological, and philosophical forms in Other Worlds. Between compasses and closerie, one leg remains fixed and standing, while the other circles, creating patterns of understanding like the swirls of colour on the book’s cover, avant-garding the terrain.

Some of these biographical details seep into the stories where they undergo transformation. The first story, “Contrition: An Isekai” (another world), is divided into five sections, each one bearing a title. The first section, “Tam Modeste,” begins with a history of Trinidad that highlights the stillness and motion of Alexis’s compasses (and Japanese genres). “In 1857, Trinidad was green and mountainous, held in the blue palm of the ocean, the skies above it as blue as the sea, but for the clouds, those wisps of white and grey, hurried along by ocean winds.” Held and hurried, fixed and circulating – these are Alexis’s polarities of Caribbean-Canadian sensibility. Tam is a shaman who works magic through the manipulation of plants and animals. In this story within a story he saves Captain James Edward Fernby, a representative of British authority on the island. Like Alexis’s set of compasses, the British presence “was not static. It moved” – eventually intruding on Tam’s secluded life. When Tam dies, he transmigrates as Paul in Petrolia, Ontario – hence Section 2, “Beginning Again.”

Like the reader, Tam is disoriented in his new life as an old man in the body of a young boy, Paul. The characters in this isekai experience “a vertiginous sense of the uncanny” in various voices and languages. Tam does much of his thinking in the bathtub (and in parentheses). He speaks English “in an accent his parents found difficult to understand.” The story is filled with humour, pathos and understanding: “Given this limitation, it is understandable that Tam’s first days in Petrolia were taken up with observation.” Adjusting to his new surroundings that include a Naugahyde armchair, he “could not stand to sit in it” -- the Swiftian comic adjustment of standing in understanding. Migrating signifiers accompany Tam-Paul who gets used to his family’s Chevrolet Impala: “he could stand it when they drove to Sarnia … for Chinese food.” In his new language, “the phonemes of English were a kind of vermin polluting his mind.” Language is both illness and cure.

Accustomed to nature in Trinidad as Tam, he now tries to adjust his senses as Paul in Canada: “He would stand still – hard to do with hormones running through him – and concentrate.” The rhythm of his running stillness is picked up by Paul’s mother Eva who “would have been alarmed to see him stand in a field, immobile.” The physical act of standing becomes part of the larger psychological landscape of understanding. While his father Roland does not understand him, he understands his father’s infidelities with female patients. Accompanying his father on medical rounds, Tam hears sexual sounds: “All of which Tam did hear as he stood by the door, thoughtfully listening, before going out of the Maillards’ house to stand at the edge of the yard behind the house.” Tam’s encompassing stance underscores his bifurcation and bilingualism.

The flow of language continues in the third section, “Skirmishes”: “As Tam’s understanding of nuance crested, there came, as well, the ability to use the new tongue efficiently.” Similarly, the reader comprehends Alexis’s nuanced perspectives. The title of part 4, “History Is Not What It Seems, It Seems,” further questions language and comprehension when Father James Fernby addresses Tam-Paul in Garifuna in Petrolia. The narrator wonders why his protagonist is “thrown into a world of which he understands so little?” Just as his author stands at Hemingway’s bar in Paris, so his protagonist stands still for long periods, staring into the distance trying to comprehend his surroundings. Tam understands Father Fernby’s Garifuna, despite his accent: “he also conveyed the thing he’d meant to keep to himself: his understanding.” Not just the language, but understanding itself – the isekai of what it seems, it seems. Through nuance and accent, Tam’s understanding of Father Fernby leads to an epiphany: “a realization came to Tam all at once, like a coagulate of reason and memory leading to an understanding.”

If a Swiftian curiosity runs through the first story of exploration, then the second story, “Houyhnhnm,” makes the Gulliver connection even more explicit. The narrator’s surname, auf der Horst, sounds like auf der Horse, just as this homonym sounds like “Houyhnhnm” in Alexis’s onomastic repertoire of suggestive names. Xan is the talking horse in this story: “in speaking with him, I understood – truly understood – that words can only hint at what a psyche needs or wants.” Language is the means toward psychological desire and meaning. Xan prefers Gertrude Stein, another off-kilter artist. (The opening patricide, “My dad, Robert auf der Horst, died some years ago,” incorporates the death of birthplace Trinidad and Hemingwayesque influence.) When Xan dies, “I understood at last how alone I had been, and I longed for company.” The story concludes with a line that the narrator’s mother draws between members of the family: “It is a line that I’ve resolved to eradicate.” Radical vision erases lines and lineages, only to resolve them in new forms and nuances.

The protagonist of “A Certain Likeness,” comments: “she would understand the distress creators feel from a different angle, but that vantage did not seem mysterious or unattainable.” Alexis specializes in different angles and (un)certain likenesses. “The Bridle Path” examines social status “until a lawyer achieves a certain standing.” The story focusses on social standing as another aspect of understanding. Betwixt and between contrition and consolation, lands and languages, Alexis’s compasses disorient, reorient, and come to some kind of understanding in other words.

About the Author

ANDRÉ ALEXIS is an author of novels, short stories, and plays. His 2015 novel, Fifteen Dogs, won the Giller Prize, Canada Reads, and the Writers' Trust Fiction Prize. In 2017, he was awarded the Windham-Campbell Literature Prize for fiction. His internationally acclaimed debut, Childhood, won the Books in Canada First Novel Award and the Trillium Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Giller Prize and the Writers' Trust Fiction Prize. He is also the author of Days by Moonlight, which won the Writers' Trust Fiction Prize and was longlisted for the Giller Prize, The Hidden Keys, Pastoral, Asylum, and Despair and Other Stories of Ottawa. Alexis lives in Toronto.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : McClelland & Stewart (May 6 2025)

Language : English

Paperback : 288 pages

ISBN-10 : 0771006241

ISBN-13 : 978-0771006241