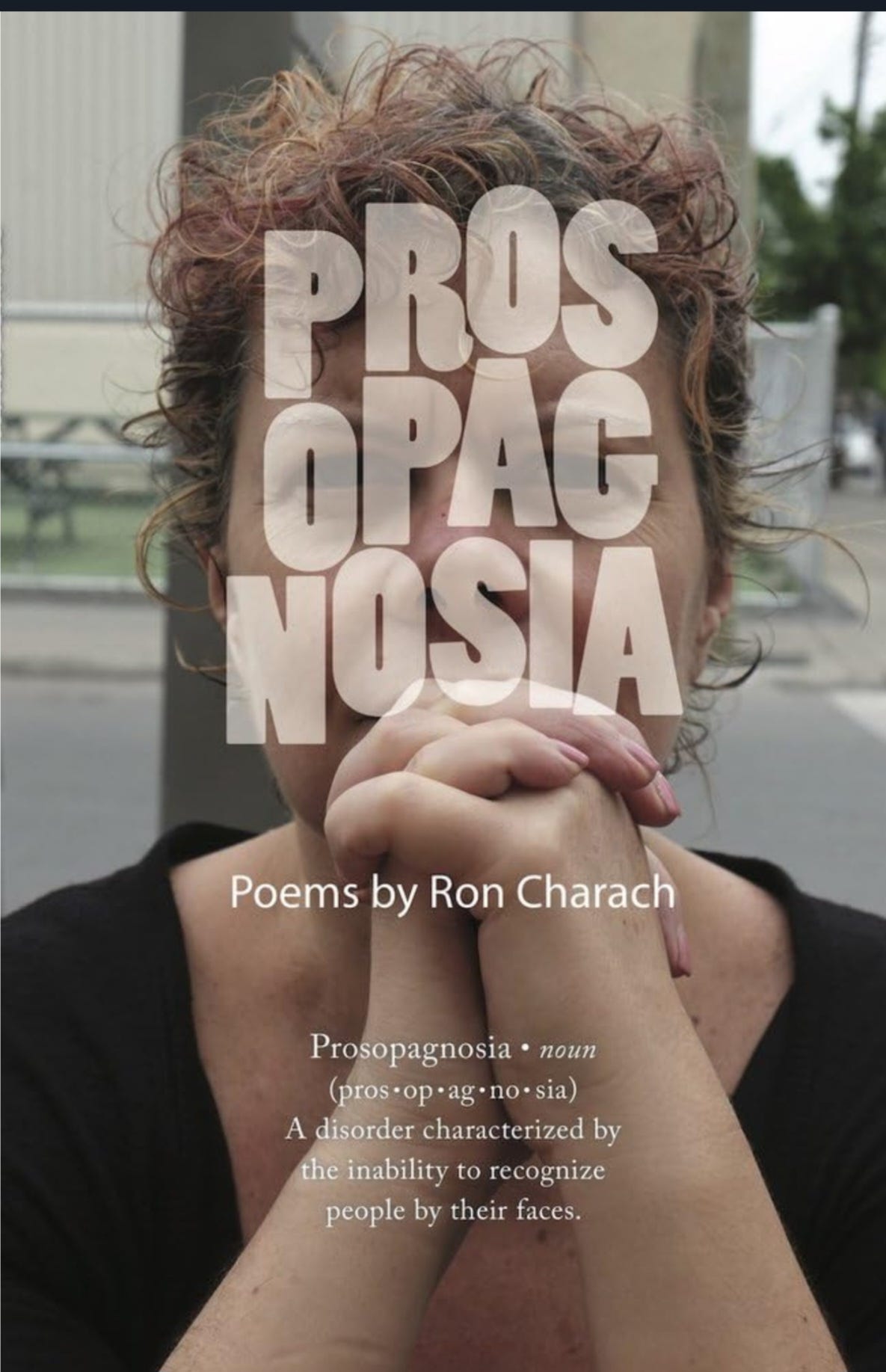

Prosopagnosia by Ron Charach

A Throwback Thursday review by Michael Greenstein

Face Off

In his ethics, Emmanuel Levinas relies on the “face of the other” to establish recognition of the other person’s individuality in any form of dialogue or encounter. In Prosopagnosia, Ron Charach turns Levinas’s philosophy on its head (as it were) to find an ethical sense in the rare medical condition whereby facial features become unrecognizable. To resolve this interplay between ethical empathy and ironic aesthetics, he listens with his psychiatric third ear and looks with his other eye. Thus, the poet’s “riff on prosopagnosia: difficulty recognizing one’s self in the faces of others, sometimes as a result of life damage.” If his given name is embedded in irony, his surname’s palindrome is suited to any dialogical quest in the ethics of encounter and mirroring reversals.

In the first poem, “Before the Reading,” the epigraph is taken from Hilary Mantel: “The dead grip the living.” To which the poet opens with his third ear’s rhyme: “Would the audience care / about the faceless poet’s mother’s hair?” The rhyme in this family romance continues in the rest of the stanza when care and hair turn to despair and chair. Furthermore, mother turns to father in the stanza’s last line – “Daddy, daddy, daddy, pin a rose on me!” The Freudian family romance becomes displaced with Harold Bloom’s “anxiety of influence” where earlier poets compete for the same audience: “Would her audience have cared / that Sylvia Plath’s sinuses were a torment?” Charach lines up Plath, Kenneth Patchen, Philip Larkin, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell, and Irving Layton through their frailties and faces against his own facelessness. After that grand tour he returns to his mother’s fate: “And you, dear reader, why would you care / about the scar that replaced my mother’s faithless breast?” The descent from faceless to faithless and rose pinned to breast ends in “the soft fall of her lilac-scented, / chestnut-coloured hair.” Thus, “Before the Reading” is concerned with biological and literary precursors in Freudian and Bloomian lines burdening the past.

Charach uses anatomy for empathy and irony in his sequence “More White Bones for the Red Man,” which includes “Thaw-Tickling Feet” and “Looking for Extra Hands.” The latter poem features “faces puffy at 4:00 a.m.” and Johny Wapamoose exclaiming “What you lookin’ at, paleface?” In the same sequence from Children’s Hospital, 1977, young Métis “wear faces like washed leather” that contrast with the poet’s paleface. In “Bad Move” the poet invokes King Kong in New York as a backdrop for a love affair where the lover is caught “priming your face.” At once more than mere synecdoche, the face comes to represent many interpersonal relationships between poet and others.

In the eponymous poem, “Prosopagnosia,” the poet asks: “Was Alex Colville reluctant to paint faces?” Whereas Colville paints car mirrors, Charach mirrors obscure faces in his dialogue with his self, projected in ironic intervals. If Colville uses a dog to obscure the face of a holy father, the poet takes his own stab at ekphrastic poetry. At the centre of the poem, the poet-psychoanalyst exclaims: “Must you always analyze things!” In this visual exchange of face blindness, I and you engage in mock-mimetic conflict: “And it's true, I had begun to see you as unpredictable, dramatic, / unable to hold up an accurate mirror.” This mirror shatters and distorts recognition and representation in the syllables of ek-phras-tic. The poem then turns inward on itself in a meta-poetic moment: “if I only have thirty-five lines to wrap up, / should I really waste any of them on: / Was Alex Colville reluctant to paint faces?” The poem concludes in the imperative of recuperation:

Next time I see you, out of context, don’t hide your face,

René Magritte-style, behind an apple or a rock,

or, as usual, behind the incessant love of your cats.

Rather, reach out, take my face in your hands and trace

my features, for God’s sake

portray me.

After the surreal trace of face, a metaphysical finale of representation.

“Awaiting Implants” combines wit, dental and psychological history to end with

the pain of

a wizened

face

Shaping these final lines, the poet voices his prosopagnosia through his missing tooth. From head to toe, the poem “At the Podiatrist” visits face: “a large-faced man in an Irish cap” and his wife whose “face contorts.” These

facials lead to “a deeper understanding / of the marriage vows.” A dermatologist of deeper symptoms, Charach performs plastic surgery on society. Indeed, “Trigger Finger” undergoes “the inspection of a plastic surgeon” to include Freud, a subliminal message, and a reminder of gun violence. From dentist to podiatrist to dermatologist, the poet-psychiatrist charts the vulnerabilities of patients and fallibilities of fainting couches.

“A Great Escape of Gas” imagines a woman delivering a baby with half a head and half a face – another form of prosopagnosia that offers “the option of retreating into thought.” “Seeking God at the Temple” ends with two-way vision between the poet and his friend who suffers from Multiple System Atrophy: “his blue eyes shine / with recognition!” In that revelatory exclamation Levinas’s other sees beyond prosopagnosia.

In “Photography Collected Us” the poet inserts surrealism with André Breton’s visit to Alvarez Bravo in Mexico. Bravo’s portrait of his wife in “Retrato de Mujer” liberates photography from the rules of European portraiture to reveal “a woman whose resolute face in three-quarter profile fills the frame.” Surrealism aligns with prosopagnosia in facial frames. Paul Strand’s subject wears a large sign that reads “Blind,” for blindness offers its own insights. Security cameras with “their fish-eye lenses gaze in dreamy all-night surveillance,” nocturnal spots of surrealism.

In his “Afterword” the poet assesses his condition and concludes that he may have a very mild case of prosopagnosia. He then riffs on his condition: “I can’t see how I fit into my family, don’t recognize myself in childhood photos.” The child misfit is father of the man rediscovering windows in song, the visual arts, and the physician’s self-healing. “Even slight changes in the appearance of the other can trigger aesthetic alarm.” Levinas’s other face meets Charach’s ethics, aesthetics, and the blurred trigger fingerprint of prosopagnosia. From the “dickhead reference” in his eponymous poem, he paints mindful games and heads in the right direction where id and superego meet.

About the Author

Ron Charach is a Toronto psychiatrist and the author of the novel, cabana the big, and nine previous collections of poetry including Forgetting the Holocaust (2011). His poems and essays have appeared in most Canadian literary and medical/psychiatric journals. Tightrope Books published his first novel, cabana the big, in 2016.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature. He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : Tightrope Books, Inc.

Publication date : July 1 2017

Language : English

Print length : 112 pages

ISBN-10 : 1988040221

ISBN-13 : 978-1988040226