Quantum: Poems by Irina Moga

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

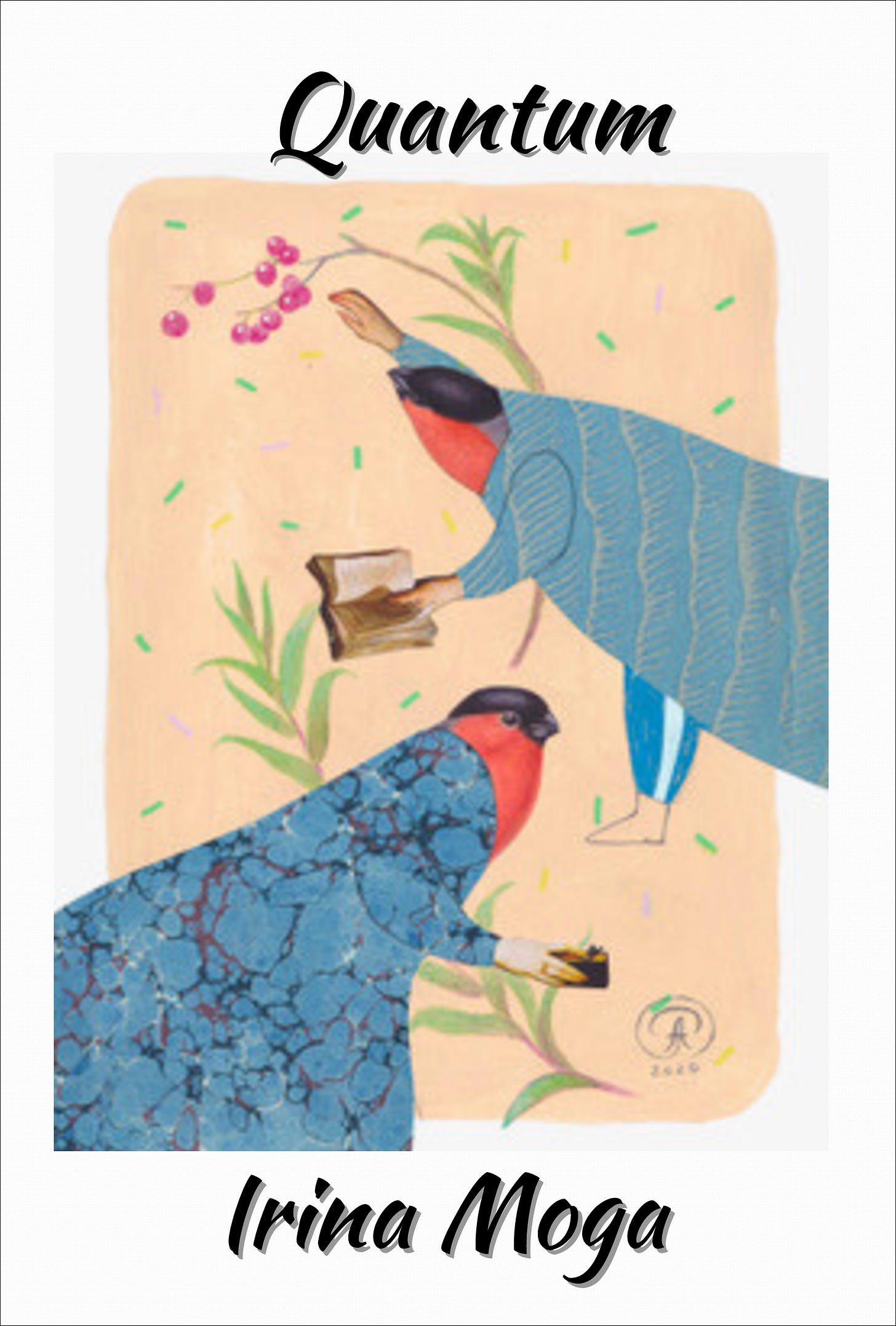

Part bird, part human, the two elegantly attired creatures on the cover of Irina Moga’s Quantum hold an open book in one hand, and with the other pluck fruit, heartstrings, and other rhythms from a colourful garden of earthly delights. These colourful figures forage for sounds, metaphors, bookmarks, and greenery. Moga’s four-part harmonies involve sentences, line breaks, spacings, and a backwash of sound; her atmosphere of seasons: a cadence of clouds, a Russian doll of memory, and staccato on random support points.

Her book opens to “Five or Six Islands” – an arbitrary yet exact quantum of six sections, each separated by an asterisk, a star of stanzas, or “snow effect” on imagined islands. Free verse floats and falls across pages of associations: “wondering if spring will ever be the same / after the snow effect of your gestures – “. Internal rhymes at the beginning and end of phrase lead to the dash, which is spelled out and spilled in indented lines in the remainder of the sentence that hints at a cold act of separation:

the cruelty with which your hands ensnare the disappearing act of chords, and their alter-egos made of air pockets.

The snare of gestures, an arc of clouds, and cruelty of chords empty a relationship, and the mood is further caught in the next shaped sentence:

an hour is but a domino effect of white petals falling from trees on a day of shadows.

An hour is timeless thanks to a domino effect which evokes Ezra Pound’s petals, shifts shapes, and echoes the earlier snow effect in a poem where effects overshadow causes.

A domino effect of long o’s encompasses alter-egos, shadows, exotic sanjo, melodies, and flow. Moga’s flow employs long dashes, shaped lines, and interspersed personal pronouns:

flooding what’s left of our awareness, -- breakers skidding towards the beach, or a capsule of dandelion pappus pledged as a hostage to the wind.

The mystery of what is broken carries through the remaining sections: “the rhythm / hitting back the wood.” This wood is word and wound “on the rebound / from the skimming the edge / of a rice paper moon.” Moga is a poet of edges, pledges, and liminal skimming “the quiet / watermark of dissipation” – the watermark of the page markings its location on islands and isolation.

Her metaphoric drift poses a question: “are we to part with the silence / that crawls on ice legs?” To which the other gnomic entity responds: “you will need to pass by five or six islands / before you can find / my home.” The poet’s quest continues “from the vantage point of a fortress, / where I am left, binoculars in hand, / -- useless in the face of blinding squalls.” Blindly, she scans the horizon of domino and sound effects and senses a deceleration: “we are besieged by snowflake variations.” Any fortress fails to protect her from the elemental sound effects of snowflakes: “here, I draw your name with a brush of hard consonants / and rushing, transparent, vowels.” In the penultimate section deceleration shifts to an alphabetical rush of letters painted on the page’s canvas.

The final section divides into two sentences of musical modulation and recapitulation in the fugue’s flow: “the domino effect of string-plucking / throws me back, mercilessly, into the azure sea -- // no islands in sight.” Her blindness offers insights across her stanzaic islands and synaesthetic musical colours: “I am one of the last ones to drown, / one of the last petals to glide / over the remoteness // of their counterpoint.” Quantum leaps and clasps quintessential elements to embrace the poet’s sixth sense.

The second poem, “Ledge,” reaffirms Moga’s edged locations. To the earlier long dashes, she now adds double colons :: that serve as barriers between words, senses, and people in the poem. From the beginning she gains her footing, a toehold on experience through alternating l and r consonants. “Submerged, long hours like spider webs hanging from a / discoloured chandelier / :: sunshine, the warmth of a foothold.” The double colon reinforces the contrast between sunshine and discoloured chandelier. The second stanza reimposes the marker between sundials and scant fog, grasped in sounds of ledge and submerged. “We sit on the ledge of the afterglow of sense :: / sundials into a nameless sea / -- a plurality of veins and scant fog.”

The poem turns on the atmosphere and definition of fog. “Fog is not a memory, though, to be explored in the space of / its rhythm -- / toppled sand mixed with brackish water.” Fog’s sound hovers between long and short o’s in that sentence. The final double colon is a reminder of barriers of isolation, a boundary between leaf and ledge, page and ensnared image. “We are alone :: quiet dead birds inside the raw filament of an / extinguished brain, / the boundary of a single nerve.” Filaments, birds, and brains fall until they are submerged: “Call it leaf, if you must.” Moga’s elegiac moods and tones recur in the “Five or Six Islands” section of the book.

The second section, “Quantum,” begins on a mathematical note with “The Mandelbrot Set.” The poet dreams that she is in her grandparents’ house in the Danube plain when an invisible hand knocks on the kitchen window. Amidst her domestic dream the surreal hand knocks and writes on the windowpane the fractal formula of the Mandelbrot set, as Moga weaves mathematics and metaphor into her tapestry. She awakens from her surreal dream “inside the fractal, in another time.” From mathematical precision to hidden patterns, Moga’s strange loops of fractal formulas quantify and qualify.

“Cloud” shapes quantum from the “abacus of the trees” to a different hint of calculus and a strange angle. Between hawthorn saplings and blackthorn winter, “Nothing much makes sense in this counting frame / except for the silence we waddle through / as if inside a cloud of particles, / a quantum motion disheveled.” This disheveled motion reappears in the eponymous “Quantum” where there is no gravity pull, “just a series of strung-out mornings, in which we attempt to / find ourselves.” Through corridors of silence, empty room, photosynthesis, a gear without a compass, and an area of error, we are “pulled by the quantum of the green, / the barely understood trident of the woods.” Woods and words photosynthesize quantum mechanics.

In the final section of this collection, “Snow Moon” contains many stanzas, each beginning with a characteristic asterisk or snowflake: “half exposed under / the wheeling moon, a spoke of / drifting snow lies low.” In this lunar and linear eclipse long o’s speak of drifts and undercurrents of snow moods. The poet moves along the edges of her moonscape and personifies an ever-shifting perspective: “The rim of his aviator glasses loosens / in the fog.” The next sentence develops the aviator metaphor: “Still, the luftmensch’s glasses fill up the air, / expecting the thinly-veiled dawn, / an unmooring / of his skinship with the light.” In this lunar eclipse the aviator’s ship is a skinship of thin veils and dermatological affinities of surface appearances.

Planetary possibilities continue in the next section’s opening “As if.” – preparing hypotheticals and similes. “The last blizzard engulfs the roads in silence,” even if blizzard may be oxymoronic in its onomatopoeic potential. And this paradox carries through to the next sentence – “Odd how snow calms the living and the ghosts” – who would be invisible in its whiteness. We arrive at a threshold and pendulum – “a joining of frozen rivers.” This confluence resumes in “Fluid, the memory of that day at the beach / under a brooding snow moon, the crevice of its understanding.” Fluid and frozen, earthly and planetary, the lunar crevice remembers and understands its history and quests for sound and image.

Running coarse rivulets through the night, like the backstory of a wax doll, its needles and pinafore washed ashore with a smack of jellyfish.

The simile domesticates the planetary with a backwash and backstory that fills in the book’s front cover with the back and fore of a costume, while the cosmic and sonic combine in tidal rhythms of back and smack, washed, shore, and fish.

The next stanza stands apart, distancing itself from descriptive or narrative flow, yet retaining its connection through commentary:

Please take what I am saying with a grain of salt – no more posturing of vowels and consonants, simply the graffiti of a lost umbrella in the rain.

This sentence travels from saltwater to fresh rain that rhymes with grain, which in turn alliterates with graffiti in a stretch of alphabetic letters.

Moga skims planets and surfaces, snow moon and smaller containers:

We are marooned in a bell jar of clay coins – brittle and whimsically coloured, imprints of summer air pinched by seagull shrieks.

The bell jar sounds Sylvia Plath, maroon and moon, alliteration of coloured clay coins, and assonance of brittle, whimsical, imprint, pinched against seagull shrieks.

The poem glides across seasons, cosmos, and domestic dwellings: “Atop the roof, the singular warbling of the dusk / settles over geraniums / with a trill of serenity.” Unspecified birds are metonymically replaced by dusk, which is followed by a further stepping aside in an allusion to Hamlet: “But let me ask: / What is your business in Elsinore?” This singular question leads to a “quietude” in random “aleatory poems” that gather “lunar maria.” Her cosmic garden consists of marginalia in a notebook, ledges, transient rotations, harmonic thumbprints, sepals, and “the question mark of cherry blossoms scent.”

She concludes her “Sticky paradise” with Ora maritima, Mare Insularum, shells, algae, and shredded passport papers in her snowy odyssey and recurrent shipwreck. Through a forest of lunar glides, Moga’s compass points eyes to a coniferous hour and quantum cadences. Her cosmic quest ends in two coffee cups, infinity mirrors tipping to a mise en abyme and quiescence of snow and reflecting the two harpies on the cover that seize moments, fractals, and lasting effects.

About the Author

Irina Moga is a trilingual author writing in English, French, and Romanian, and a member of The Writers’ Union of Canada. The author of six poetry collections, she brings a distinctive voice to contemporary literature, one interlaced with lyrical depth.

Her collection Variations sans palais (Éditions L’Harmattan, Paris) received the 2022 Dina Sahyouni International Literary Prize in France. Irina’s poems, short stories and reviews have appeared widely in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published extensively on Victorian, Canadian, and American Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : DarkWinter Press

Publication date : July 1 2025

Language : English

Print length : 92 pages

ISBN-10 : 1998441288

ISBN-13 : 978-1998441280

You are most welcome.

Thank you! I am grateful and much moved by this review of "Quantum". And I appreciate the undercurrents of humour in it. :=0)