The Eclipse of a Victorian Heroine: Queen Esther by John Irving

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Early in John Irving’s sixteenth novel, Queen Esther, the narrator describes teacher Thomas Winslow’s pedagogic lesson, which also applies to readers of the novel: “he could teach them to read well.” When he visits Dr. Larch’s orphanage to adopt eponymous Esther, the narrator draws attention to the doctor’s desk: “The typewriter was the centerpiece; the surrounding stacks of pages had a writerly symmetry.” In turn, this writerly symmetry draws attention to self-referential acts of postmodernism in the novel that may be contrasted with a more dominant strain of realism in readerly appeal to a broader audience. Much later in the novel, Thomas Winslow’s grandson, James, takes up the tricks of the trade: “This was a writing lesson James Winslow would learn,” for he is the protagonist of Queen Esther, engaged in a metafictional process of novel writing within the novel. With its cinematic grasp and cerebral reach, Irving’s fiction may be characterized by a readerly and writerly asymmetry.

“With its cinematic grasp and cerebral reach, Irving’s fiction may be characterized by a readerly and writerly asymmetry.”

This dichotomy between the mass appeal of readerly fiction and a more limited audience of writerly fiction is further complicated by Irving’s introduction of his “teacherly” term surrounding his character, where his roman à clef becomes a roman à thèse concerning techniques of wrestling or issues of abortion. (One chapter is titled “The History of Abortion in America.”) From the very beginning of the novel, Thomas Winslow appears as “the very essence of teacherly.” If he is short in stature, he makes up for it in his expansive mind and lineage: “the prevailing impression of Thomas Winslow was teacherly.” Midway through this 400-page novel, his grandson in Vienna poses questions to his German tutor: “There was something merely teacherly, even perfunctory, in Fräulein Eissler’s answer.”

At times, Queen Esther is a teacherly text in which John Irving instructs his reader in multiple directions, frequently engaging in dramatic dialogue to offset his writerly mode with its intertextual and metafictional twists and turns.

The novel’s title alludes to the biblical Book of Esther and the mysterious orphan Esther Nacht, who is deposited on the doorstep of New England’s Home for Little Wanderers in St. Cloud’s, Maine. This home contrasts with the larger wanderings of Irving’s plot from the history of the Winslow family arriving in New England in 1620 to James Winslow’s escapades in Vienna three centuries later. Like his author, Thomas worships Charles Dickens and teaches his favourite novel, Great Expectations, along with other Victorian masterpieces. Like Dickens, Irving engages in social causes and uses caricature as part of his humour. Thomas constantly repeats to his wife – “Right you are, Connie” – in readerly rather than writerly fashion. He gives “Town Talks” on George Eliot and the Brontë sisters as well, and these town talks contrast with the gossipy ways of the conservative-minded citizens of Pennacook, New Hampshire. “To the townspeople of Pennacook, the Winslows’ family money mattered more than their Mayflower ancestry.”

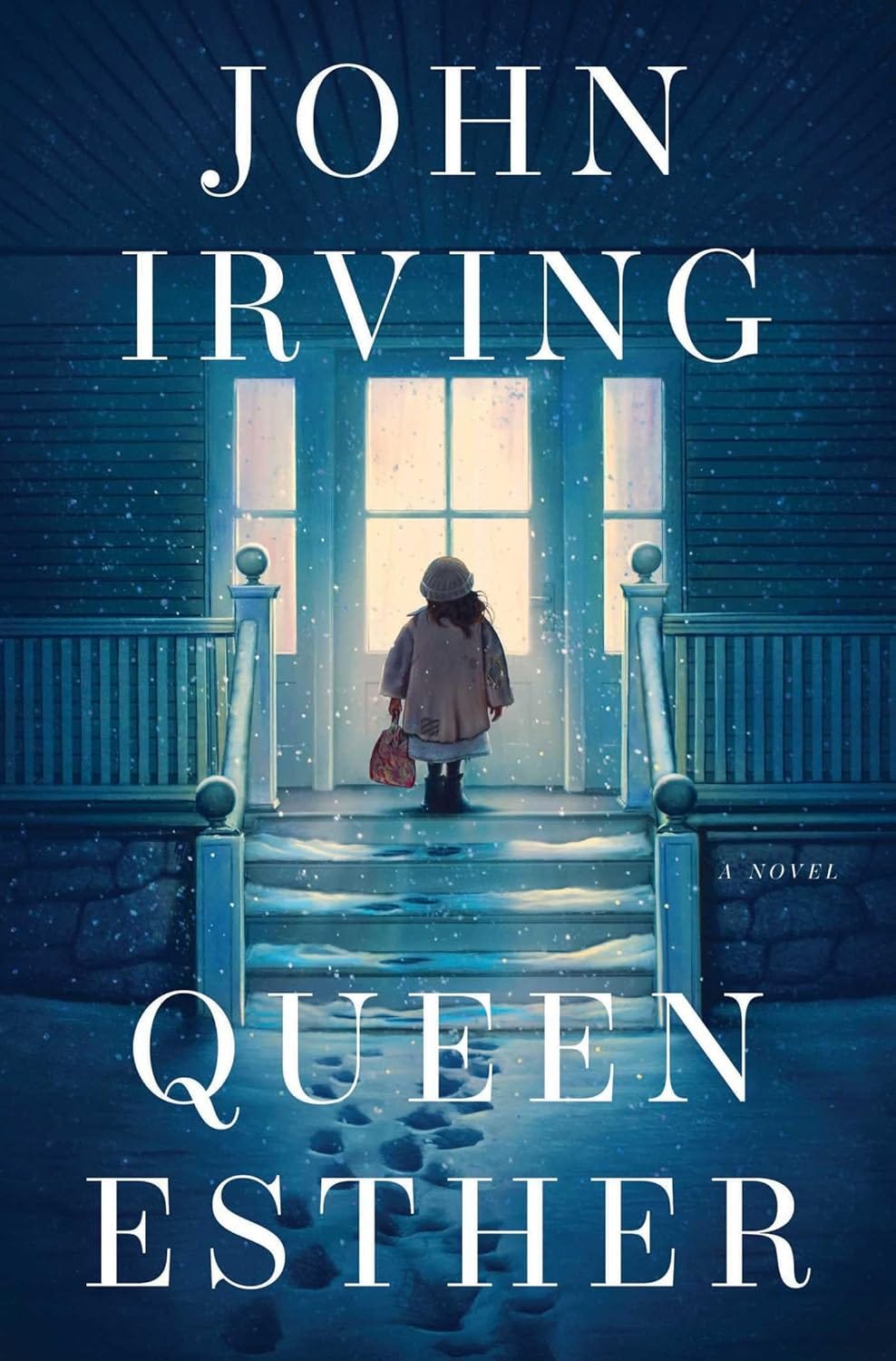

The Winslows travel to St. Cloud’s to adopt an orphan to care for their fourth daughter, Honor. The girl in question is Esther Nacht, who was left on Dr. Larch’s front porch during the winter of 1908, and who will become an au pair to the Winslow family. Her names are telling: Esther from the Purim story means both hidden and star, and indeed she remains hidden for most of the novel, as she gives way to her birth son James Winslow. Nacht refers to Kristallnacht, Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, and Kaffeehaus Nachtmusik in Vienna, where James and his roommates spend much of their time. In the novel, Esther is eclipsed by the night and hiddenness of plot and narrative; furthermore, she is hidden by a tattoo across her body.

Her hidden tattoo is intertextual, derived from Jane Eyre: “I care for myself.” Charlotte Brontë’s fuller passage is: “The more solitary, the more friendless, the more sustained I am, the more I will respect myself.” This statement interacts with the novel’s epigraph from the Book of Esther: “For we are sold, I and my people, to be destroyed, to be slain, and to perish.” Esther’s self-respect is part of her identity, tattooed onto skin and soul. She examines various fonts from tattooist Anchor Al and prefers Goudy and Didot styles. Jane Eyre’s words wrap around her torso and serve as a kind of palimpsest for Irving’s ink marks.

Esther Nacht is resourceful and resilient in her return to her Viennese birthplace and Jerusalem destination. What is written in stone may be reinscribed on skin. Queen Esther is a learning experience, and “the Winslows knew that they would learn a lot from her.” She continues to instruct her adopted family: “Fifteen years later, the Winslows were still learning from Esther Nacht.” Irving learns and teaches from his Jewish text.

Esther bonds with Honor. When she learns German and Yiddish, Irving indulges in phallic humour with the etymology of “penis” in these languages. This provides a kind of foreplay for the sexual activities that take place in Vienna with unusual forms of ménage à trois and impregnation. Asexual Honor informs her parents about her pact with Esther who will become pregnant and give the baby to Honor to raise. The two-moms idea is a recurrent circumstance in the novel. “That was when Thomas and Constance Winslow realized that their grandchild Jimmy – who wasn’t yet conceived, much less born – was already a preexisting idea.” Irving’s telescope peers into the future with his plotting of ends and beginnings. The harmony within the Winslow family is Dickensian in its caricature and burlesque, and contrasts with the conservative ways of the townspeople of Pennacook and the tragic events of World War Two.

In Vienna, Esther meets Moshe Kleinberg or Moses Little Mountain, a wrestler who becomes the father of her child and who also gives birth to Irving’s wrestling indulgence. Forbidden by the Nazis from wrestling professionally in Germany, Moshe immigrated to Israel in 1934. Irving also indulges in the history of circumcision in a chapter entitled “Old Testament Girl,” which ends with Esther’s words, “it’s just a penis – don’t think too much about it.”

Thomas Winslow teaches his grandson Great Expectations by reading aloud and tells him that Dickens’s punctuation is a form of stage direction. While Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead provides an American adaptation of Dickens, Queen Esther offers a very different approach. Although Irving’s dialogue may be Dickensian at times, his narrator lacks Dickens’s exquisite stylistics of breathing spaces and brushstrokes. Consider the brief opening paragraph of Great Expectations, where Dickens compresses and balances his focus on Pip: “My father’s family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip.” Pip names his palindrome, which is shortened from the longer Pirrip palindrome, in a mirroring and nesting of sound, sense, and identity. Parataxis further encloses these palindromes of birth, infancy, and the authority of a tombstone’s marker. Dickens tattoos tombstone and psyche, even as Abel Magwitch wrestles Pip in the graveyard. Where Dickens constructs atmosphere and poetry, Irving’s narrative moves on without a lingering Dickensian soundtrack. Dickens mirrors the roadway ingeniously; Irving may try to imitate his precursor, but the Inimitable One resists such attempts.

One of the ways for Jimmy to avoid being drafted into the army is for him to become a father; another method would involve a knee injury caused by wrestling. Chapter 15 begins with Thomas giving his grandson a copy of Henry Fielding’s eighteenth-century bildungsroman, The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling – a foundling for the child of a foundling. The narrative shifts abruptly to wrestling in Vienna, as we become acquainted with Annalies Eissler (who looks after Jimmy in Vienna) and Leopold Spiegel (the “Little Mirror” who owns a wrestling club in Vienna). Jimmy’s roommates in Vienna – Claude and Jolanda – provide much of the sexual humour through the rest of the novel.

Jimmy embarks on his first novel The Dickens Man with teacher Tom as his protagonist. We then return to “suplay” wrestling, as Irving grapples with his plot, straying from character to character, topic to topic, and ink addiction to tattooing and tale of a tub in which the aptly named dog, Hard Rain, defecates in the bathtub at the sound of thunder. Jimmy’s “mom and Esther lived in the background, like peripheral characters in a novel.” James Winslow is a “horse with blinders,” glancing at peripheral characters, backgrounds, and Esther’s hiddenness beneath tattoos and history’s texts. Right you do and write you are John Irving in Esther’s nightly expectations.

About the Author

A dual citizen of the United States and Canada, John Irving lives in Toronto. Queen Esther is his sixteenth novel.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published extensively on Victorian, Canadian, and American Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : SIMON SCHUSTER

Publication date : Nov. 6 2025

Language : English

Print length : 416 pages

ISBN-10 : 1471179133

ISBN-13 : 978-1471179136