Raymond Klibansky: A Life in Philosophy, Conversations With Georges Leroux

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Raymond Klibansky, the fascinating philosopher who lived through most of the twentieth century and taught at McGill University, is hardly a household name; nor, for that matter is Nicolas Cusanis, the fifteenth-century German philosopher, who was one of the many subjects Klibansky studied. Thanks to Alberto Manguel’s lucid “Foreword” and Georges Leroux’s equally accessible conversations with Klibansky, his life and thought come to life in the most vivid manner.

Born in Paris in 1905, he attended French primary school, but in 1914 his family was forced to return to Germany because of the First World War when he entered the Goethe-Gymnasium in Frankfurt. At the age of fifteen, he attended Odenwald School for a more liberal education in contrast to the authoritarian pedagogical tradition of Wilhelminian Germany. The children of Thomas Mann and Ernst Cassirer went there as well. For university, he shifted to Heidelberg, where he came under the influence of Karl Jaspers. What makes his life so fascinating is not just his ideas, but also his travels to and from various cultural capitals – Paris, Heidelberg, Hamburg, London, Oxford, and Montreal – where he encountered important and interesting people at each stage.

In his work on the Renaissance, Klibansky studied Cusanus’s mysticism and negative thinking, along with Ernst Cassirer and Aby Warburg. The 1920s were a productive decade in Germany, in contrast to the 1930s, when the Nazis took over and forced the philosopher to leave for England in 1933. Along with art historian Erwin Panofsky who left Germany for the United States, Klibansky published Saturn and Melancholy, completed in London in 1939, but not published in England until 1964. We are reminded of the Greek origins of melancholy: black for melan, bile for choly. Michelangelo wrote that his joy was melancholy, and sadness in music reinforces the idea of self-awareness and meditative retreat from the world. While in England, he met Albert Einstein, and they discussed the idea of founding an institute for exiled academics in Jerusalem. He became a British citizen in 1938, and in 1942 he was recruited into the Political Warfare Executive where he engaged in counter-propaganda – hardly the stuff of ivory-tower abstraction. After the war he was invited to McGill where he became Professor of Logic and Metaphysics.

Klibansky’s Lithuanian grandfather was descended from the Vilna Gaon, an opponent of Hasidism; his father retained his Orthodoxy in Frankfurt. On his mother’s side, his family had been living in Bavaria for centuries, and he speculates that they may have arrived with the Romans. He had a happy childhood with his German governess and French maids. In one of his anecdotes, he describes his vacation near Frankfurt when the emperor passed by, and the young French patriot refused to doff his hat as a sign of respect. From then on, he left his hat at home out of respect for his mother and the emperor. This bilingual, dual citizen was well on his way to becoming a citizen of the world in multiple languages.

He knew Hannah Arendt and considered her more a writer than a substantive critic, and her reputation inflated. Similarly, he critiques Freud on the subject of melancholy. He also believes that the Weimar Republic failed to offer inspiring symbols, while the Nazis were able to fill that gap with their propaganda and visible symbols. In contrast to the Nazis’ demonic structures, this book includes a photograph of Aby Warburg’s library in Hamburg, which was a paradise and a labyrinth. Indeed, what is striking about this period is the contrast between an almost Golden Age of Germany in the 1920s and the Nazi takeover a decade later. Klibansky reminds us that during the war Sweden was neutral, but the Swedish allowed the Germans to use their trains to transport soldiers to Norway.

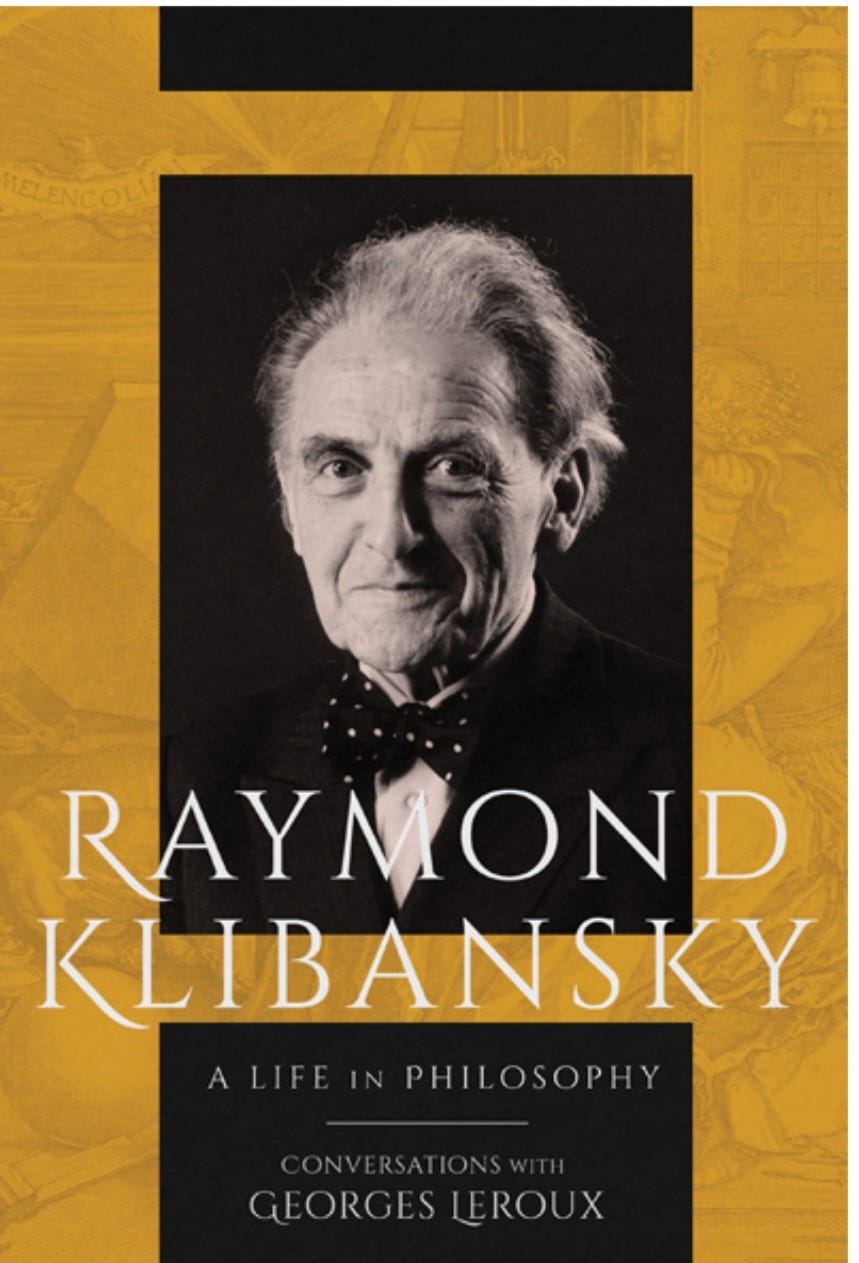

Each of the photographs in the book adds life to Klibansky’s account. What stands out most, perhaps, is the philosopher with his bow tie, a symbol of his elegant sensibility and cosmopolitanism throughout the twentieth century.

About the Author

Georges Leroux is emeritus professor in the Department of Philosophy at the Université du Québec à Montréal.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : McGill-Queen’s University Press

Publication date : Sept. 16 2025

Language : English

Print length : 300 pages

ISBN-10 : 0228014379

ISBN-13 : 978-0228014379