Renewal: Indigenous Perspectives on Land-Based Education In and Beyond the Classroom, Edited by Katya Adamov Ferguson, Christine M'Lot

Reviewed by Anne Smith-Nochasak

Renewal: Indigenous Perspectives on Land-Based Education In and Beyond the Classroom, the second book in the Footbridge series, is edited by Christine M’Lot (Anishnaabe educator and curriculum developer) and Katya Adamov Ferguson (Settler educator and artist), with the support of Land-based education consultant and reviewer Dr. Brian Rice (Kanienké:haka, professor in Kinesiology and recreation management), with contributions from many Indigenous voices, through a variety of texts: essay, poetry, art, photo, and music. This work was developed “to support educators in integrating Indigenous land-based pedagogies in both the classroom and outdoor settings,” and provides a comprehensive guide for all those who aspire to undertake land-based education.

From the beginning, we are reminded that land-based education is not a variation on outdoor education, but a complex way of seeing and being in the world. Indigenous land-based education entails not only learning about the land while on the land, but also learning from the land. And “land” is not simply the ground beneath one’s feet or property; it is all aspects — land, water, sky, and animals — in which we find our connection and are part of a complexity of interconnections. It is stressed that this set of complex relationships includes the spiritual aspect.

The editors openly admit that they are not experts in land-based education, and that they will be learning with the reader, studying the texts shared by Indigenous “thinkers, artists, creatives, and activists.” These contributors show how to live “as relatives to the land”. Their input forms a “living text”, providing a starting point for engaging with Indigenous voices and methodologies. The goal is ultimately to develop a profound awareness, an appreciation of “our intrinsic connection to the land.”

The unique perspective of Indigenous education is recognized, as are the special qualities that each Indigenous population brings to this education. Non-Indigenous educators are encouraged and invited to learn and work patiently “with a good heart”, as facilitators in the work.

I like the way they bring out the fact that students who face challenges in the regular classroom become leaders when learning shifts to an outdoor environment. Of note too is one contributor’s observation that colonialism removed Indigenous peoples from their landscapes, their source of strength. This has been a profoundly traumatic experience, and reconnecting with the land is seen as healing.

Land-based education calls for commitment before it formally begins —considering safety lessons, building partnerships with the Indigenous community, conferring with Elders and Knowledge keepers, prioritizing Indigenous language, honouring the protocols of the culture, and involving Indigenous youth are significant aspects of the groundwork. They stress the importance of appropriate practice of ceremony: It should be done by the right person—an Indigenous elder or a Knowledge keeper. Knowing how to do it doesn't mean you have the right to do it. These are important considerations, and the way these are brought up early in the conversation is appreciated.

Also highly welcome is the comprehensive checklist provided, clear and organized, for educators to use as they prepare to set up a program.

The comprehensive chart in the introduction enables the educator to see exactly what is included in one neat page: The four sections are delineated, and within each section the contributor, their nation, the title of their text, the type of text used, the learning level suggested, and connected concepts are readily available. This overall organization forms an excellent reference for ongoing use, and this one is extremely clear.

The four parts of the book — Knowing, Being, Doing, and Becoming—each have their own section, but the editors point out that they interconnect and overlap. Knowing refers to the knowledge systems developed by Indigenous peoples, being focuses on the philosophical perspectives that guide how Indigenous people understand and interact within the world, doing refers to the practical application of Indigenous knowledge in daily life and cultural practices, and becoming explores the process of growth, with lifelong personal and communal development. Each section begins with an overview that establishes connections with the Indigenous worldview. I appreciate the way the contributor biographies are placed at the beginning of their text, which enables us to immediately meet them, and appreciate their expertise and background as we read on, rather than having to search for them in an appendix somewhere. These biographies form part of the learning process, by establioshing a starting point. And each contributor has their own medium of presentation. The texts are short and relevant, with the focus not on memorizing content, but on interacting with it on many levels.

To this purpose, following each text there is a set of personal connections (given by the editors), followed by educator connections and classroom connections, each with appropriate prompting questions individualized specific to the text under consideration. It is not just the students who reflect, but also the educators, because this is not theoretical knowledge being passed on to the students, but an interactive process involving all teachers and students with the contributors and with the experience itself.

These connections are set up in phases: Beginning, Bridging, and Beyond. This designates not a grade level but an experience level, which is a more inclusive approach. A fluidity is suggested here, a capacity for growth rather than being locked into a specific grade level. The use of the term “phases” is significant, for it connects to the cyclical relationship of the phases of the moon, and the cyclical relationship of land, water, and sky.

Applications to the Land Back movement follow each text, examining the ways in which each text aligns with the themes surrounding land dispossession and the enduring impacts of colonialism. Decolonizing thinking and actions is seen to be necessary, a fundamental questioning of western ideas of property and how they have separated people from their ancestral territories and knowledge.

And then each entry finishes with a list of relevant resources.

A thorough overview like this provides a solid grounding that prepares educators for their task, for how they deliver the program depends on such understanding.

In each text, the beginning, bridging, and beyond questions are structured to allow participants to respond to questions that they understand. We no longer have to disengage because the question is beyond us—there are questions and activities that include us all. Each has something in their comfort zone, which provides just enough challenge to encourage engagement.

A few points of interest from the many that exist are mentioned here: In Nicki Ferland's article, the connection to the land in an urban setting is especially insightful. Elsewhere, Dr. Tasha Beeds talks about “being your bundle,” the bundle being those physical and spiritual things carried by the Indigenous person, and then suggests ways others can be a support to the bundle—decolonizing our thinking, deactivating our colonial energies and identifying what we, the colonial, need to do. There is a task it seems for everyone; there is no exclusion. And I shall think long on the idea of teaching as having a spiritual aspect.

After the photo essay, one of the editors reflects on the problems of a place-centred curriculum, particularly when we are teaching geography of places we have never seen. Anchoring the curriculum in where we are will perhaps help in this regard, for we are not learning about places, but place. (Notice that the geography section does not mention places, but customs, natural cycles, interactions, etc. particularly relating to food.)

There is also the refreshing concept of unlearning, introduced by Mi’kmaw scholar Marie Battiste: unlearning the ways we have been using, making space for a new way of looking at things. Elsewhere we read of the use of European-based games in perpetuating the goals of colonialism, and the “taming of the wilderness” implied in Scout activities.

In Mah!, we are led to consider approaching the world with an understanding of our obligations to live in “respectful relations with each other and with all our relations on the land, in the water, and throughout the cosmos.”

Another contributor cautions against rushing to implement land-based education without understanding what it's all about. It begins with reflection and coming to understanding; especially, you have to listen well. [Mah!]

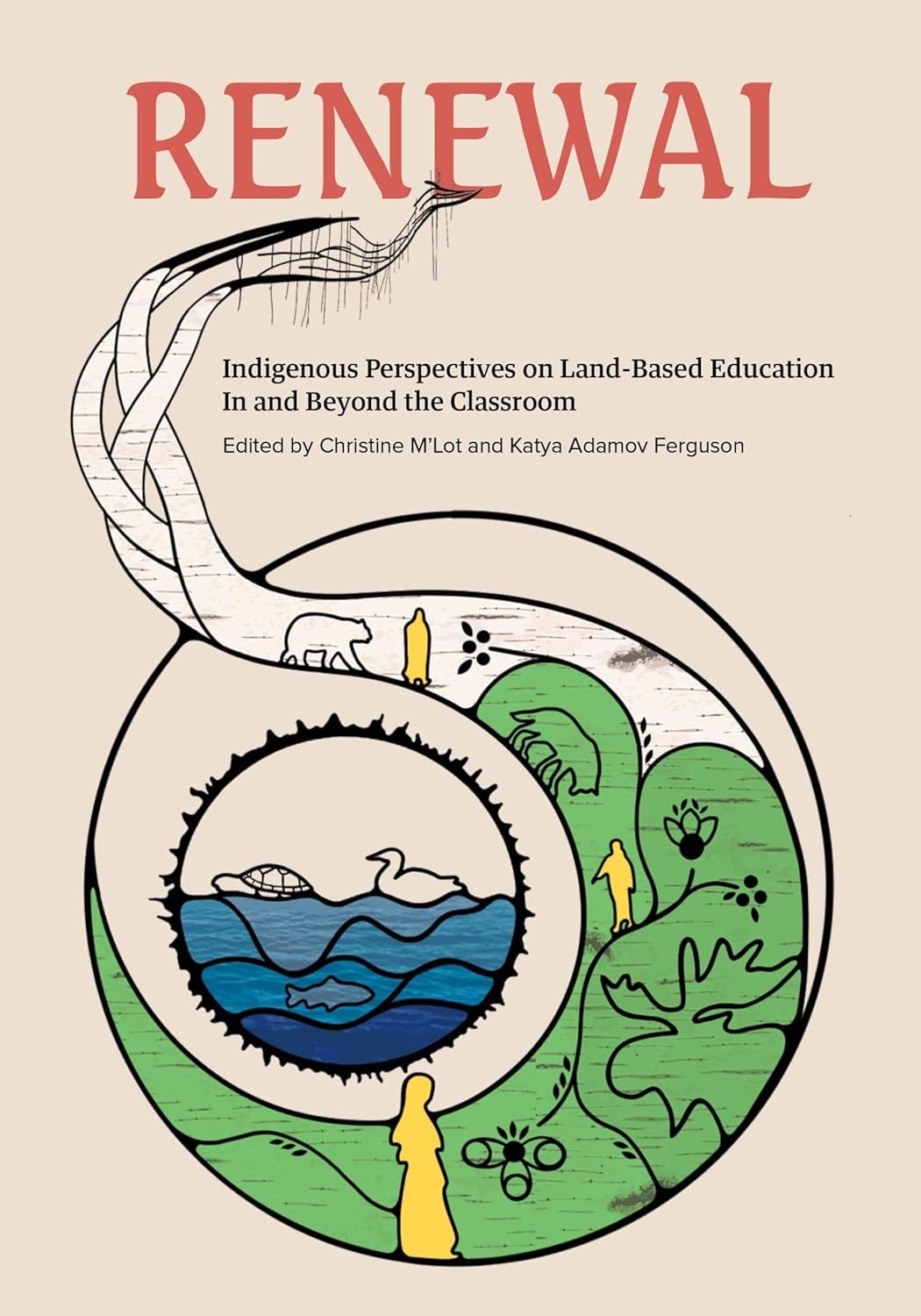

In the final selection, Reanna Merasty explains the process of creating the artwork for the previous volume Resurgence, in which she depicted the intertwining paths of knowledge. For Renewal, the artist expanded the original motif, but went further, creating a circle symbolizing a wholeness encompassing water, fire, and earth. The figure from the Resurgence cover is on the path now to renewal, as an educator focusing on the Indigenous ways of being.

It is a very satisfying read, yet also one that challenges a colonial world view at its core level, leading us to reflect and to ponder, while awakening a desire to learn to live and teach this way—in our classrooms in whatever form they take. Offered with honesty and commitment, this is a must-read for all educators.

About the Editors

Katya Adamov Ferguson (she/her/hers) is a settler educator and artist of Ukrainian and Russian ancestry from Winnipeg, Manitoba. Katya is also an arts-based researcher engaging with creative and critical methods to support place-based inquiries and deeper understandings of land-based issues. She is committed to creating partnerships and supporting Indigenous resurgence.

Christine M’Lot (she/her/hers) is an Anishinaabe educator and curriculum developer from Winnipeg, Manitoba. She currently teaches high school at the University of Winnipeg Collegiate and is the associate publisher at Portage & Main Press. To learn more about her past and current education projects, visit her website at Christinemlot.com.

About the Reviewer

Anne M. Smith-Nochasak grew up in rural western Nova Scotia, where she currently resides and teaches part-time after many years working in northern communities. She has self-published four novels using Friesen Press’s services: A Canoer of Shorelines (2021), The Ice Widow (2022), and two instalments in the Taggak Journey trilogy: River Faces North (2024) and River Becomes Shadow (2025). She is currently a member of the Writer’s Federation of Nova Scotia and likes to feature Nova Scotia settings in her writing. When she isn’t writing or teaching, Anne can be found reading, kayaking, gardening, renovating, or exploring the woods with her golden dog Shay while her cat Kit Marlowe supervises the house. Anne can be reached through her website https://www.acanoerofshorelines.com/ or on X, IG, and FB.

Book Details

Publisher : Portage & Main Press

Publication date : Sept. 23 2025

Language : English

Print length : 224 pages

ISBN-10 : 1774921677

ISBN-13 : 978-1774921678