The Art of Looking Back by Theresa Kishkan

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Mirror, Mirror

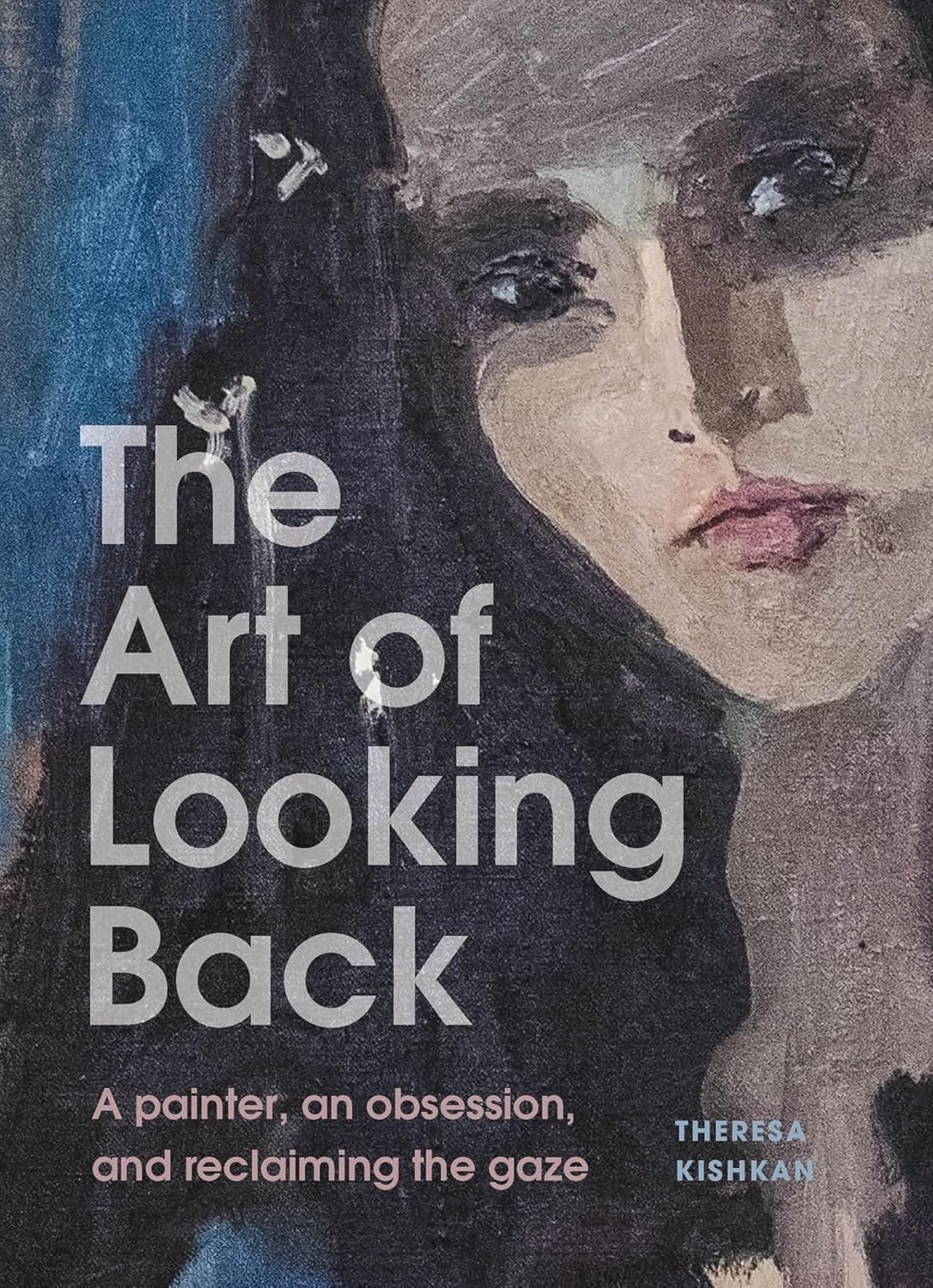

Doubling and doubting are at the heart of Theresa Kishkan’s The Art of Looking Back, a compelling memoir about her relationship with Victoria painter, Jack Wilkinson. Considerably older that the author, Wilkinson became obsessed with her and painted her in beguiling, yet inappropriate ways that she tries to comprehend as an older woman looking back on her younger self. Several portraits add poignancy to the thousands of words devoted to their fraught relationship caught in the aesthetics of hindsight. In addition to these intriguing paintings, Kishkan includes references to other writers to frame her portrait of the artist as a young woman. Looking back is a mirrored experience of the older writer looking back over her past, as well as her younger self in the portrait looking back at her every time she passes by the earlier painting.

“Her story involves an understanding of boundaries, not just between men and women, but between art and society, and the nature of frames and framing.”

A sentence from Julia Kristeva’s “Stabat Mater” aptly serves as the book’s epigraph: “Let a body venture at last out of its shelter, take a chance with meaning under a veil of words.” Now a mother and grandmother, she stands at the foot of her own image where she has her own cross to bear. On one level the book looks back and sideways to these secondary sources that lift veils and ventures in Kishkan’s belated coming of age under the scrutiny of a painter’s gaze. Her text opens with a description of her portrait: “Every morning I descend the stairs from my bedroom and there she is: me, at twenty-three.” If the rhyme addresses the poet, so too does the doubling of stairs and stares, for the model constantly stares at her own image, even as Wilkinson had stared years ago with his brushstrokes. This painting features dark hair, strewn with flowers. The double stare of younger self looking at older woman who in turn gazes back: “I remember the mornings I’d begin the descent to the kitchen and stop after two stairs.” When she first meets the painter, there is a “doubletake” in the language of ambiguities: “I turned to see Jack. I turn now to see Jack in almost every room of my house.” That turning point involves another doubling verb: “I see him taking me in. Was I taken in? I was.” Her narrative takes turns in the aesthetics of hindsight as she builds her home and life.

Based on the evidence from his earlier infatuation with his own daughter, Wilkinson is culpable in his unrequited longing for Kishkan. What saves the staring match from falling into narcissism is the mismatch between the older woman and her younger version, as well as the mismatch between older painter and his youthful subject. Furthermore, these paintings take on archetypal dimensions with the introduction of Hesiod’s The Homeric Hymns and Homerica: “But the woman took off the great lid of the jar with her hands and scattered all these and her thought caused sorrow and mischief to men. Only Hope remained there in an unbreakable home within under the rim of the great jar, and did not fly out the door.” These complex emotions of home and hope are scattered throughout Kishkan’s telling to pair up with an image of the Karyatids in Athens – those female figures who support the porch of the temple. These symbols of strength resonate throughout the book and accompany the author in the construction of her house in British Columbia. In addition, her Athenian visit occasions Freud’s visit: “I only doubted whether I should ever see Athens” because of his family’s poverty. Freud’s visit to Athens was an instance of his dissatisfaction with home and family.

Kishkan is a lid lifter, bearer of ceilings, and stair dweller who scatters thoughts and emotions with keen insight, Homeric hymns, and the Limners of Victoria’s artistic scene. Her portrait with dark hair, strewn flowers, blue vest, and lateral gaze haunts the pages of her memoir. Her story involves an understanding of boundaries, not just between men and women, but between art and society, and the nature of frames and framing. Looking at her younger self in a blue waistcoat, she instructs “Step back. Step back.” – a poetic refrain and pas de deux on the steps of that staircase where her shape is “lovingly limned.” Just as the poet avoids narcissism, so the reader is wary of voyeurism (caveat lector) in the interplay between italics and parentheses: “(That first ardent letter, accompanying the drawing. Sheryl and her boyfriend saw me open it, maybe I read the letter to them, I don’t remember, but mark the moment, remember it, because of something that happened later.)” An italicized sentence slants the obsessive portrait: “Sometimes when you dust the painting, you need to straighten it afterwards and you feel woozy, pushing the frame with your duster, your own face behind glass, at a distance, the years refracting, changing direction.” Aside from the shift in pronouns for self-scrutiny, the sentence is held up by a black-and-white drawing of satyr Jack and naked poet on a beach with the superscript “You & I” – sexualized karyatids supporting the text.

Even more disturbing than that lascivious illustration is an incestuous nude painting of Jack’s daughter, Gina, who is five years younger that Kishkan, but “We shared a resemblance …. The model that was almost me …. We could have been sisters.” Yet another instance of doubles. This portrait features twelve-year-old Gina naked, getting out of bed to shut her door for privacy, the black doorknob ominous against her bright flesh. The father’s fixation is part and parcel of his doting on nubile models that he sees as “archetypes.” Transfixed in an almost fugue-like state Kishkan stares once again halfway down the stairs: “Look away, look away,” she admonishes as if in the midst of a fairy tale. “The gaze has turned, it has turned.” Her repetition captures the rhythm of time, trauma, and transformation. A framed metamorphosis: “For years the gaze kept me at a distance but some mornings it was a mirror, a threshold” – Lacan’s doubles and liminal spaces for rites of passage. The young poet on the stairwell evokes W.B. Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan,” but also Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess”: “When she looks past me, her eyes slightly hooded, is she being evasive or all-knowing, or is she simply bored?” Kishkan’s dramatic monologue.

She escapes to Ireland for the Atlantic rush and seclusion; she escapes to the Pacific for isolation closer to home. She rhymes him out of her life: “In his care, his keeping, draped in a Japanese veil or with flowers scattered in my hair.” Through her own veil she exorcises evil – “as far as I needed to go. Which was Turlough, near Castlebar in County Mayo.” At the very least, Kishkan’s flowing words, thoughts, and rhythms overpaint Wilkinson’s portraits in a pentimento of counter-discourse that purges shame and guilt.

About the Author

Theresa Kishkan lives on the Sechelt Peninsula, BC with her husband, John Pass (a poet and winner of the Governor General’s Award for poetry in 2006 and the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize in 2012), in a house they built and where they raised their three children.

She has published 16 books, including Euclid’s Orchard, a collection of essays about family history, botany, mathematics and love (Mother Tongue Publishing, 2017); a novella, The Weight of the Heart (Palimpsest Press, 2020); and Blue Portugal and Other Essays (University of Alberta Press, 2022), a collection of lyrical essays.

Her books have been nominated for many awards, including the Hubert Evans Award and the Ethel Wilson Prize. Theresa’s essay collection Phantom Limb received the inaugural Readers’ Choice Award from the Creative Nonfiction Collective in 2008. Thornapple Press will publish The Art of Looking Back: A Painter, an Obsession, and Reclaiming the Gaze, a literary memoir, in May 2026.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published extensively on Victorian, Canadian, and American Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : Thornapple Press

Publication date : May 29 2026

Language : English

Print length : 216 pages

ISBN-10 : 1997702061

ISBN-13 : 978-1997702061

Thanks for introducing Levinas into this discussion, Sheila. It is indeed fascinating: the painter controlling his subject, and then the more mature woman studying her younger self as “other.”

Once facial features combine with nudity, the painting may lose sight of the humanity of the other, and perverse aesthetics may take over from any ethical approach.

Looking forward to this. I'm sure it's a gem. I've read Kishkan's work before.