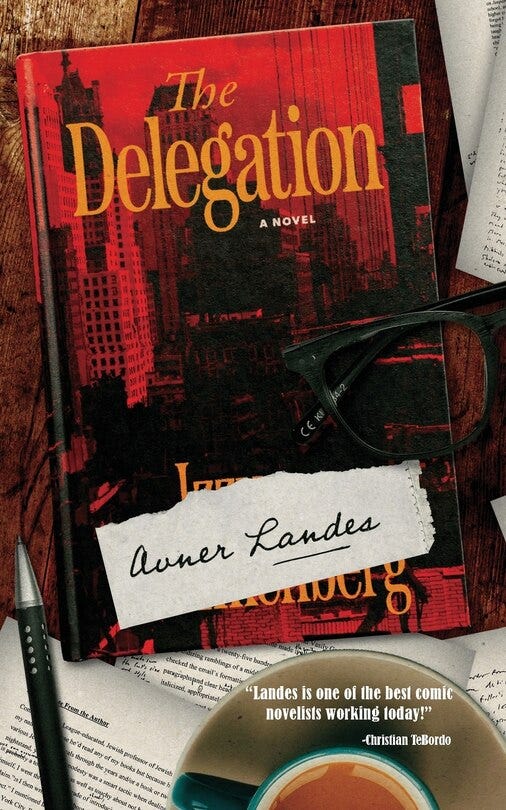

The Avner Landes Interview

Danila Botha Interviews the author of The Delegation

The Delegation is one of the most ambitious and brilliant novels I’ve read in a long time. I’ve been a fan of Avner Landes ever since his sharply funny, very literary debut novel, Meiselman: The Lean Years which was published by Tortoise Books in 2021. The Delegation was published this past April by Operation Dodecahedron, and it’s fantastic. It was a pleasure to talk to him about writing, craft, his inspirations and more.

DB: Let’s start with the three (!) concurrent story lines, which is a feat in itself. What was the writing and editing process like? Did you write them at the same time or separately? (I’m trying to picture what a draft with so much moving in time would look like, and it seems so challenging.) Do you always conceive of the book in this format or did the idea evolve over time?

AL: Looking back on the decision-making that went into this non-traditional format, I’m both surprised and relieved at how organic the process was. While the book contains three concurrent storylines, it’s really two narratives—the primary novel about two Jewish Soviet artists on a world tour in 1943 and a middle section featuring a note from the fictional author of that novel. (The bottom section consists of footnotes to the author's note.) Ambivalence and self-doubt plagued me throughout the writing of this historical novel. The stupidity of attempting to write a historical novel!

DB: That’s so funny. But I can relate, even within the context of short fiction, writing historical fiction is such a challenge.

AL: So, after finishing a section of the historical novel, I decided to write about this ambivalence and doubt, and I soon found myself writing another book entirely, one about an author grappling not only with this anxiety, but with the question of how a writer is to know what they should be writing.

Figuring out how to present these intertwined narratives was a persistent challenge. My instinct as a writer is to work within traditional structures and then find ways to disrupt them in meaningful ways. I never want to begin with the assumption that a work should be unconventional and full of shenanigans. This is a recipe for gimmickry.

DB: I agree.

AL: I could this format of three narratives stacked one on top of the other clearly in my head, but the problem was that Microsoft Word doesn’t support this format. You need special publishing software to do such things. So, for a long time, it existed only in my mind.

DB: Wow.

“As a writer, you want to have that feeling throughout the process of not knowing whether a book will work or not, because this is the feeling you want readers to have when reading…”

AL: When I started submitting the manuscript, publishers struggled to appreciate my vision. Understandably, it sounded convoluted to them. Eventually, I hired a layout designer to format the first twenty pages, which helped clarify the vision. Even then, it wasn’t until readers engaged with the book that I truly felt it had succeeded. As a writer, you want to have that feeling throughout the process of not knowing whether a book will work or not, because this is the feeling you want readers to have when reading, the question of, “How will this all come together in the end?” The reader will only ask this if the writer had the same question.

DB: Your writing is always so sharp and funny, and irreverent at moments, I laughed out loud so many times, and yet the mix of sincerity and irony here works so beautifully.

AL: I won’t be cheeky and pretend I don’t intend to be funny on the page—I enjoy both reading and writing humorous fiction. But the writing wouldn’t work if I were to approach it like a Borscht Belt comedian. Several months ago, at a funeral, the grandson of the deceased remarked that everything his grandfather said was funny and that everything his grandfather said was dead serious, too. That perfectly captures how humor should work in prose.

DB: That’s so interesting.

AL: It can’t only be funny.

DB: Right, of course.

AL: But the writing it is more instinct than formula. Something is funny, but how does it push forward the story? That’s not something Borscht Belt comedians tend to worry about.

DB: Can we talk about narrative choice? Meiselman’s nemesis from your previous novel who is fleshed out and given a voice here. Can you tell me about the decision to bring this character back in a different way? It was so satisfying to read from his point of view.

AL: I don’t want to reveal too much about the narrator—I want that to be a surprise for readers. But whenever I begin a piece of writing, I focus on establishing limitations for the narrator or protagonist, particularly in how they perceive the world. Limitations bring out the best in writers, something I often notice in your work.

DB: Thanks so much. Yes, I find limitations so generative too.

AL: Limitations lead to stronger storytelling because people actually operate with limitations—we all have blind spots.

DB: Totally.

AL: So, what are the protagonist’s blind spots? That question became especially important when deciding to bring back Shenkenberg, a writer who, in the first novel, has gained a certain level of fame and serves as Meiselman’s nemesis. Throughout the writing of my last book—and even after finishing it—I kept returning to the question of who Shenkenberg really is as a writer. Originally, I envisioned him as a past version of myself, representing the writer I was when I first started out, back when my ideas about writing were vastly different.

DB: That’s so interesting, to consider oneself as a writer at the same time as you’re building a fictional world.

AL: With this book, I wanted to explore that question more deeply—what exactly were my early ideas about writing and writers? How have they evolved over the years? In this novel, Shenkenberg is struggling to understand what it means to be a writer and the question of whether he is writing for an audience.

DB: I can see that. Aside from everything else, it also very much is a book for writers. In choosing a specific period with real people no less, in a fictional context, were you initially concerned about tone and how readers would receive it, or how it would be categorized, in terms of genre or in publishing terms? There’s this sense of artistic freedom, this freeform energy that comes across, and I’m wondering if it was always the case with this book, or did it evolve that way with time? And also, how does one achieve this kind of creative freedom in writing? (I’m asking for a friend, haha)

AL: Over the years, I’ve trained myself to think less and less about audience. . . as much as that’s humanly possible. The only audience that truly matters during the writing process is the writer, since they are the one who must read the work over and over.

Every word must continue to delight me on the hundredth reading, or the book will never get finished. Freedom comes from never assuming that anything I write will actually get published.

DB: I think humility is important too.

AL: Every piece of writing for me begins as a personal challenge, an attempt to do something new or, as I mentioned before, to impose certain limitations on my characters or the writing.

DB: I love that.

AL: Saying what a book is about is marketing speak. But if I were speaking to writers, I would introduce my book through the writing challenge I took on with the work. The overwhelming majority of my challenges end in failure, so I never expect my writing to see the light of day. With this book, it wasn’t until I was about ninety percent finished that I paused and thought, ‘Huh, this worked. This is a book.”

With this book, being historical fiction and centered on real people, I did feel certain pressures, not necessarily to represent the historical figures with perfect accuracy, as that’s ultimately an impossible task, but to be respectful. (Well, maybe not Einstein, whose reputation needed a bit of a correction.)

DB: Ha, I loved that part.

AL: Fiction will always be a representation rather than a precise reflection of who people are. My goal was to do justice to their situation. These were artists living under impossible conditions, making choices shaped by a desire to survive. Morally, they failed, but I want readers to approach their flaws with sympathy and understanding. While writing this book, I often thought about something David Bezmozgis once said: “Irreverence is only possible where there is reverence.”

“The fun I have with my characters is only possible because, at my core, I deeply respect them and the struggles they endured.”

DB: That’s great, I’d never heard that quote before, but he’s one of my favourite writers too. Natasha and Other Stories changed my life as a young writer.

AL: The fun I have with my characters is only possible because, at my core, I deeply respect them and the struggles they endured.

DB: Can we come back for a second, to historical fiction? I was reading that you had some ambivalence about the genre, which you feel a little bit as the reader, but it only adds to the tension. What was your research process like? As you wrote each section, were you conscious of having a conversation with your text and your readers as you wrote it?

AL: That’s a great question. In many ways, this book is a conversation I’m having with myself about the purpose of historical fiction. I was overwhelmed at the start of the writing of this book. The sheer volume of source material was daunting. I didn’t feel up to the task. I didn’t know if I had interest in even attempting it. I don’t enjoy non-fiction. It’s fiction, fiction, fiction for me at all hours of the day. I’m a fiction writer. I’m not a historian. And that distinction is what this book is about. But this is the same conversation we all have in our daily lives. We encounter complex issues and convince ourselves that our opinions carry the weight of expertise. Guns, taxes, the environment. We know it all. But in reality, we are nothing more than storytellers, trying to tell ourselves stories that make sense of the world we live in. It would be a far better world if we understood we are not experts, but storytellers searching for the right story. Humility is a feature of the latter and not the former. A story is not the truth itself, but a vessel that carries many truths within it.

DB: Well put.

AL: This book can be read in any order the reader chooses. They may alternate between the three sections, read the top section straight through, or even begin with the middle section. There is no right or wrong way. The question is how the reader responds to encountering details that reshape the narrative they’ve already constructed. Does the reader allow the story to evolve in their mind, shifting with each revelation? Or does the reader hold onto that first iteration of the story they construct?

DB: Tell me about your literary influences; your style and voice is so unique but I get hints of Roth and Auster and even Foster Wallace, although I prefer your style of footnotes/ maximalism. It also in places reminds me of David Bezmozgis’s work, sharp but full of a certain indefatigable hope.

AL: Good call! Roth and Auster were certainly my earliest influences, the ones who first sparked my excitement for reading and writing. Then came Bellow, Malamud, Michaels, Paley, Friedman, and many of the other usual Jewish suspects.

DB: I could talk for hours about Grace Paley. Her short stories are some of my favourite of all time.

AL: But true literary influences often work their way into our writing in more subtle ways. They aren’t just the writers we admire; they’re the ones who show us how to do something small that propels our work forward in profound ways.For me, those writers are George Eliot, Henry James, Stanley Elkin, and Stephen Dixon. With this book, my influences were explosive historical novels that push the genre in unexpected and unexplored directions—Curzio Malaparte’s The Skin, Michael Winkler’s Grimmish, Bram Presser’s The Book of Dirt, and many others.

I love that you describe my book as carrying a ‘certain indefatigable hope.’ I think both of my books share that quality. At their core, they explore the same central question, one that preoccupies much of my day-to-day thinking: Can people truly change? The idea my books express is that, yes, change is possible, but it’s never grand, never a sweeping transformation. Instead, it happens in small, almost imperceptible ways. We’re lucky if we get to experience even one of these slight shifts.

DB: Reading this book, it felt so alive and so necessary; The book touches on what your character calls the “crisis of chutzpah,” but also what it means to create art under less than ideal, or even antisemitic circumstances. What was it like to produce this now, in the world we’re currently living in?

AL: I recently met with a book club, and the member who introduced me spoke about the book’s resonance in his own life. He shared the story of a colleague—a math professor in Russia—who was arrested and stripped of his job for criticizing Putin and the war in Ukraine. I first conceived of this book nearly seven years ago and began writing it over four years ago. Throughout the process, I worked hard not to think about the political implications of the story or what it might say about our current moment. Shaping a narrative around contemporary politics risks turning it into a didactic work. Only after finishing the book did I begin to recognize its relevance to everything happening in the world today. Its resonance comes from a deeper, more troubling truth—history is always repeating itself.

But it’s equally important to acknowledge that no two stories, no two histories, are exactly the same. The protagonists of this book are two artists who were so devoted to the promise of the Soviet Union that they refused to acknowledge any evidence that conflicted with the story they told themselves. My hope isn’t that readers walk away believing this book reinforces the stories they tell themselves. Instead, I hope it challenges them enough to alter, even in a slight way, these stories.

DB: In both your previous novel, Meiselman, which I also loved, and now in The Delegation, there’s a lot of commentary on Judaism itself. Who is your ideal reader or audience for this book?

AL : My books contain a significant amount of Jewish content, including untranslated passages in Hebrew and Yiddish… What I learned from Meiselman is that you can never predict who will connect with a book. Women, especially those between the ages of 30 and 60, have embraced Meiselman—a group I had assumed, before publication, would loathe it. But after witnessing their enthusiasm and reflecting on it, it’s very clear to me why the book resonated with them. My anticipation was that they’d give it an unfair reading, when, in actuality, they were better readers of it than me. So, I don’t know which readers will gravitate toward this new book, but I’m eager to find out. Ultimately, it’s the readers—not the writer—who understand a book best and teach the writer how to read what was written.

DB: I agree. Thank you so much for chatting with me, Avner, and for sharing all of your insights and thoughts.

About the Author

Avner Landes works as a ghostwriter and editor. His first novel is Meiselman: The Lean Years (Tortoise Books), a finalist for the 2021 Chicago Writers Association Book of the Year. He lives in a suburb of Tel Aviv with his wife and two children.

About the Interviewer

Danila Botha is the author of the critically acclaimed short story collections, Got No Secrets, For All the Men (and Some of the Women) I’ve Known, which was a finalist for the Trillium Book Award, The Vine Awards and the ReLit Award and most recently, Things that Cause Inappropriate Happiness. The title story was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. The collection won an Indie Reader Discovery Award for Women's Issues, Fiction, and was a finalist for the Canadian Book Club Awards, and the Next Generation Indie Book Awards. She is also the author of the award-winning novel Too Much On the Inside which was optioned for film. Her new novel, A Place for People Like Us will be published by Guernica this October. Her first graphic novel will be published in 2026 by At Bay Press.