the book of sentences by rob mclennan

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

A gather of . . .

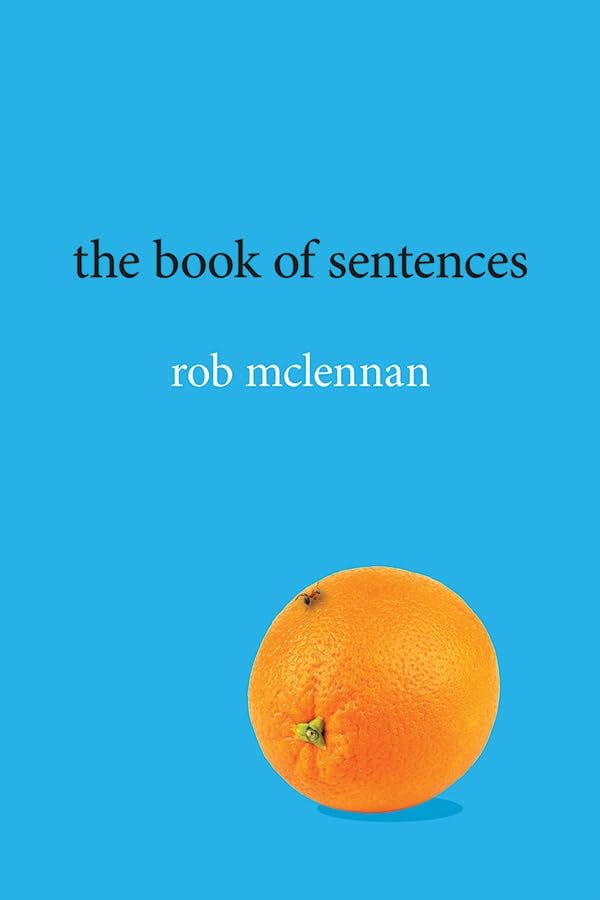

Prolific, playful rob mclennan flexes the book of sentences between fragments and run-ons, between domestic clips and stretches of horizon, between wee daughters and a long arc of ancestors, and between autobiography and the lines of others. On the cover of his latest collection of poems an ant crawls on the surface of a glowing orange, interface of insect on bright fruit, Hallowe’en black on orange, trickster or treater of irony where the reader attempts to penetrate the surface of language. That diminutive ant reappears at the bottom of page 50, opposite “Autobiography” – a footnote, bookmark, and guide to the poems from the first section, “Book of Magazine Verse,” to the eponymous second, “The Book of Sentences.”

The cadence and grammar of the cover give way to a series of epigraphs that focus on beginnings thereby foregrounding the function of epigraphing. The first of these intertextual sentences is from Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s A Treatise on Stars: “Everything arrives energetically, at first.” Which implies that entropy inevitably follows the sidereal line.

The second epigraph from Etel Adnan’s Shifting the Silence invokes celestial firsts, mingling astronomy and archaeology:

When we name things simply, with words preceding

their meanings, a cosmic narration takes place.

does the discovery of origins remove their dust?

The horizon’s shimmering slows down all other

perceptions. It reminds me of a childhood of emptiness

which seems to have taken me near the beginnings of

space and time.

mclennan begins with smaller domestic details that reach beyond his horizon to grasp cosmic connections. Patti McCarthy’s wifthing rounds out the third epigraph: “this sentence is from several failed attempts,” which hints at the process of revision in the book of sentences, and the coupling of domestic and cosmic sequences.

The first section, “Book of Magazine Verse,” drops the definite article to focus instead on numbered poems, fragments within a longer collage. He begins with “Four poems for Parentheses,” the magazine title calling attention to what is parenthetic, edgy, marginal in these sentences that eschew parentheses but bracket silent spaces (“Seven poems on a return to the world”). (Also, “parentheses” begins with parent, the source of family sequence.)

The first couplet understands Ottawa’s notes of weather: “I shall begin with slush, and the bone cold prominence / of icy blacktop. To break this open.” Not only is slush an interface between snow and water, but it is also onomatopoeic in its sound break of caesura and preparation for the assonance of long o’s that follow. In turn, those openings slush against the closing consonance of begin, bone, blacktop, and break. Patterns and patters appear in the flock “of stopped, stalled cars” on his Alta Vista Street with its own filtered vistas. The frozen flow of trochees winter and patter singsong: “Snowsuit, snowsuit, backpacks. Domestic chain.” From the domestic and bureaucratic documents of school closures, the poem turns to Auden’s Icarus lyric:

Having fallen from the sky,

remaining children skate haiku

over playground inclines: one line,

one line,

stop.

Skated haiku traps the sound of the diminutive playground and poetic field in singular lines. The full stop at the end of children’s games recalls the stopped cars in earlier inclined lines.

The poem weaves infinitives – To see, To gesture, to know, and To wonder – to further open the rhythm of sights and sounds in a cadence of ice. The poet responds to the crossing guard’s stop sign: “loops of language” forge cadence and cable into a new beginning for weathered sentences, body, and birth. He binds unplowed paths to his “three-winged plow” between two limits of Barcelonian tides and Ottawa’s ice, sea stars and prosaic field in skated sentences. Equally at home with microscopic and telescopic vistas, these smaller sentences fragment cosmic distance while focusing on domestic details in phrases of near and far.

Consider “Three poems for Tiny Spoon” whose magazine title points to mclennan’s concerns with domestic diminutives. Each poem may be read as a separate entity or as part of a triptych structure.

A string, tied down to earth. February sun,

compared to music. In full view

of the nightly plow.

The poem itself is a winter string tied through punctuation, breathing space, view, and voice. Monosyllables in the first sentence cling to the string before the separating space that leads to “down to earth” – a phrase of spatial (dis) orientation and reference to vernacular language sung in the synaesthetic music of February sun. Since no principal verbs are to be found in these three sentences, the act of reading or writing serves to fill in grammatical blanks and full daytime views.

The second poem adds a sentence and teases some verbs, beginning with an infinitive:

To bury, nature. Sketch in a notebook. The altitude,

an accumulated thirty centimeters. Echoes,

blooms to black thread, white.

This poem is tied to the first in buried nature, which is down to earth, while altitude polarizes underground, and thirty centimeters measure the nightly plow. In an accumulated sketch, lines echo back and forth, words black on white, and thread tied to string. Echoes of lower-case e.e. cummings abound.

The third poem further accumulates these threads of thought:

An immortal

stillness, gathers. Somewhere, light is filtered. Somewhere,

a thin form, mostly paper, melts

beyond the snowy limbs.

Earlier music gathers its stillness, sibilance, and rhythmic caesuras – a gathering on the snow-white paper blackened by letters, sounds, and forms of February. These limbs in full view filter this gathering of tiny poems spooned in snow.

“Poem for Train” picks up speed in the process and progress of locomotion:

Enough grain. Pointed west,

and fast enough

to lose all fear. I was on a train.

Grain and Train rhyme the names of two poetry journals for this journey, defined in self-referential terms:

a compact meditation

of grammar,

grounded. My thirtieth year:

Against the vastness of Ontario and west, the poem compacts sounds and rhythms in a grounded grammar of grain. The outer landscape narrows to bracketed lines: “parenthetical towns and city-stops, / a break-line, gathers.” Once again, mclennan gathers grain, grammar, and personal experience in line breaks: “Speed // enough to empty.” His speed is sufficient to measure these decades, decode the years and the final training of astral sight: “Third star / to the right,” after a night of long winds that gather a wish to see the world and the sounds of spreads, said, and sped. For every gathering, mclennan’s postmodernism counters with dispersal, dissemination, and scattering.

“Ten poems for Stephen Cain’s fiftieth birthday” engages once again with the dynamic of dispersal and gathering:

The endlessness of experimentation

across

this grey anchor

of urban agglomeration.

The stretch of the first line is curtailed in the second, to be resumed in the space between stanzas, and anchored in rhyming agglomeration. The rhythm of the non-sentence sentence continues in the second poem where principal verbs multiply:

In an absence of wholeness,

poems neighbourhood, gather,

quarter-centuried,

tethered.

This gathering of grammar turns the noun of neighbourhood into a satisfying verb linked to “quarter-centuried” and syncopated with gather and tethered. Poems gather in ten units across pages and other distances to celebrate a birthday.

The third poem ears the experience of reading, writing, and counting the decades: “One listens, for patterns” – the singular scattered among phenomenological apercus, each comma curled and flinted into significance. Montage of West Toronto Junction or confluence of Indigenous trails shares the page with “paralexicon” by “reversing a word / inside a word.” mclennan’s code for small presses and lower-case name intertexts Raymond Souster with a “mannerism of made speech” and an ambulant footnote.

The final poem in “Book of Magazine Verse” gathers its precedents and prepares for the remaining poems in “The Book of Sentences.” Our pandemic enters the space between long journey and short flight. “Picture the house. These hands / are spilling. Rise up, gather.” Hands and house disseminate the single seed, “patterned / clipper,” and layered rubble. Negating nouns and verbs, the poet writes his own impossibility to conclude: “My father’s texts // have reached their end.” Postmodern paradoxes end, only to begin again in a father’s rebirth.

“Autobiography” begins directly in two directions: “Listen: any two are opposite. The green / is cleaved. This infinite summer.” The cleavage of gather and scatter, as the poet writes his life in the tether of group chat, endings, and revisions. “Remaining on the ground with me. With them. / They gather sticks and weeds.” With his children the poet gathers his groundwork.

“Song for a quiet voice” delineates his great-grandparents’ piano through pandemic, Ottawa, and his daughters’ playing. Small and communal, his “wee girls” inherit the music of departed grandparents: “Informal gatherings of songs both popular // and spiritual.” mclennan’s family gathering ends with the inclusion of Rosmarie Waldrop: “the period // often does not mark the end of a sentence, but a / pause.” the book of sentences pauses poems and periods in a quiet voice, Ottawa’s sotto voce of hibernation.

Pauses, ellipses, and tropes assemble and digress in a pulsing dance-beat. In the first section of “Coordinates” his wife Christine weeds while he words “clusters / of interlude, possibility.” To the second section: “What else the wind gathers, lone hedge / that separates properties.” The poet surveys, and the breeze coordinates stanzas and metaphors, shifting from Christine to Clarissa Dalloway in Virginia Woolf’s floral design of garnered bouquets between modernism and postmodernism – a domestic retrieval of dustpan and broom, montage and collage. In “Namesake” “Every figure is unique, / and with uniqueness, gathers.” “Sketchbook:” names his daughters Rose and Aoife as “wee monsters.” His panopticon of meditations oversees belonging where “original inhabitants might very well have gathered.” After pandemic, “Ars Persona” exhibits family tumult: “A disassembly of get-togethers, / gatherings.”

“As in Nowhere, No-One” begins with an Olympic-sized 400 metres before turning to a “garnering // of nesting fowl” and Priscilla Uppal’s millimetre. “The sentence, gathers” with crucial commas in “Approximation.” His “two wee girls” gather swimsuits in “Reading Kaveh Akbar’s Pilgrim Bell by our new inflatable pool.” Melody requires repetition, and lists repeat. “Associations, gather” fragments in “Composition.” In “Six anti-ghazals for Phyllis Webb” he enlists John Newlove, Douglas Barbour, Joe Blades, David Donnell, Michael Dennis, and Gerard Manley Hopkins to shore up all the syncopated fragments, book iambic sentences, and gather as much in the multifarious play of language.

About the Author

rob mclennan is an editor, publisher, critic, and the author of more than fifty titles. He has won the John Newlove Poetry Award, the Council for the Arts in Ottawa Mid-Career Award and was longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize. He lives in Ottawa, where he is home full-time with the two wee girls he shares with Christine McNair.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : University of Calgary Press

Publication date : Oct. 15 2025

Language : English

Print length : 162 pages

ISBN-10 : 1773856480

ISBN-13 : 978-1773856483