The Burning Bush Garden

A Throwback Thursday Essay by Michael Greenstein

“I could conceive of another Abraham for myself –.” Franz Kafka

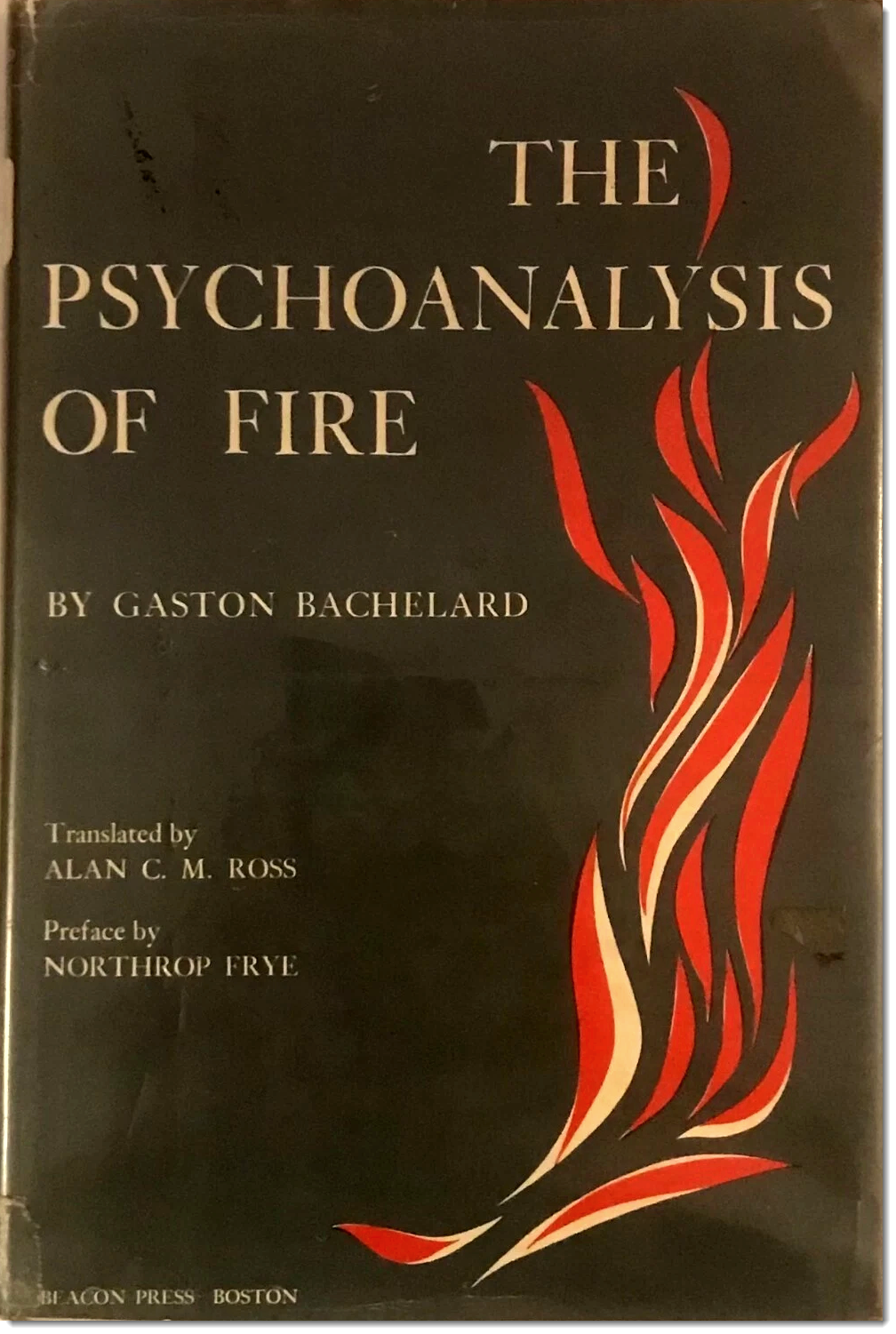

In her “Introduction” to Northrop Frye’s The Bush Garden, Lisa Moore notes a potentially destructive element within the creative process: “Art-making has the feel of sacrament and sacrifice, necessarily wrapped in hazard tape, all aflame.” This dual nature of sacrament and sacrifice appears in Margaret Atwood’s “The Two Fires” in The Journals of Susanna Moodie, from which Frye has borrowed his title. In the chain from Moodie to Atwood to Frye, Frye pens the “Preface” to Gaston Bachelard’s The Psychoanalysis of Fire with its “tongues of fire.” He notes the linkage of fire-myths to analogy and identity, wherein fire spreads to a multilingualism. Atwood’s fires involve the burning of Susanna Moodie’s house as well as a forest fire – domestic destruction and nature’s vengeance – but they spread beyond that in the Canadian imagination. In the Canadian-Jewish imagination, fires multiply through sacrament and sacrifice, beginning with Abraham’s firepan and aborted sacrifice, and carrying through to Moses’s burning bush, followed by a range of rituals, historic conflagrations, and Hebrew-Yiddish dialectic across the Diaspora.

Frye singles out A.M. Klein’s novel, The Second Scroll, and applies the notion of a promised land and Maccabean victories to the Canadian literary landscape. The discrepancy between Hebrew and Yiddish (a bilingualism of dual fires) is present in Klein’s name – his biblical given names opposed to his diminutive Yiddish surname – and appears in his poem, “Autobiographical,” where a dream of “pleasant Bible-land” contrasts with Yiddish slums. The poet pictures his mother blessing candles, “Sabbath-flamed,” the two candles representing memory and observance in contrast to Atwood’s two fires. Frye’s allusion to the Maccabees, however, invokes a fuller flame of the menorah to celebrate Chanukah, the Festival of Lights, with the miracle of oil burning far longer than it should have, much as Moses’ burning bush is not extinguished. These historical flames assume yet another form in The Second Scroll, for Klein wrote to his publisher in 1951 to praise the novel’s cover design: “the Second Scroll bursting forth – as from flame – from behind the curled parchment of the first.” He continues enthusiastically: “the new and improved form of the palimpsest! Above all, a commentary.” With its Yiddish and Hebrew allusions, Klein’s improved commentary incorporates Biblical patriarchs, teachers, priests, and prophets going forth towards a promised land, yet not fully arriving after delays and detours in the Diaspora. Abraham’s sacrificial fire is never lit, while Moses’ burning bush is never extinguished.

In Klein’s multilingual narrative, his messianic Uncle Melech Davidson prays, “a flame tonguing its way to the full fire of God,” and continues a tradition back to the “lightning of Sinai.” This narrative is interrupted by the announcement of a pogrom in Ratno, and the Genesis chapter ends with the Holocaust: “he was enveloped by the great smoke that for the next six years kept billowing over the Jews of Europe – their cloud by day, their pillar of fire by night.” Like the two languages, the two Jewish fires alternate between sacramental offerings and sacrificial victimization.

To encompass the Diaspora, Klein’s nameless narrator travels to Morocco. This encounter with the Sephardic world may be enhanced when compared with the French and North African experiences of Jacques Derrida and Hélène Cixous who share his interest in multilingual play, Joycean neologisms, Kafka’s enigmas, and Talmudic marginal commentary. A first intersection may be found in Derrida’s Judeities which focuses initially on Kafka’s “Abraham, the Other” before turning to his own past in Algeria where at school he hears an anti-Semitic insult. Derrida’s trauma: “Before understanding any of it, I received this word like a blow, a denunciation …. A blow struck against me, but a blow that I would henceforth have to carry and incorporate forever in the very essence of my most singularly signed and assigned behavior.” Like circumcision, the word “Jew” cuts into his being – “the figure of a wounding arrow, of a weapon or a projectile that has sunk into your body, once and for all and without the possibility of ever uprooting it.” These traumatic roots cut across body, psyche, Diaspora: “It adheres to your body and pulls it toward itself from within, as would a fishing hook or a harpoon wedged inside you.” Like Klein, his inner dilemma finds a therapeutic outlet in writing, spreading the words of Diaspora.

Derrida frequently appears in dialogue alongside Cixous whose Algerian background overlaps with his. Her “memory and life writing” appears in Rootprints, whose title takes us back to transplanting roots and forward to radical postmodernism with its diasporic discourse. On her father’s side of the family tree, Sephardic ancestry; on her mother’s an Ashkenaz background that includes a photograph of her bearded, kippa-covered Slovak great-grandfather Abraham Klein studying the Talmud. “My mother has always told me about my Talmudist great-grand-fathers: I have imaginary images of these old men who spent their nocturnal life studying the Talmud. I see them – there are photographs – I see these old men with their skullcaps, an enormous book before them.” She goes on to interpret this unknowable text: “The Talmud is as infinite in its commentaries as our experience of sexual difference and its translations.” In her own margins she juxtaposes Clarice Lispector and Kafka whose journals and correspondence she reads. Her mother’s Nordic family had two fates: the concentration camps on the one hand; on the other, a scattering across the earth, which gives rise to her “worldwide resonance.” Her resonance of rootprints brings us back, after these diasporic Mediterranean detours, to Kafka’s enigmatic parable, “Abraham.”

Unacknowledged legislators of the Diaspora, Montreal lawyer Abe Klein reads Prague lawyer Franz Kafka through the trials and judgments of the Mosaic Code. “Abraham” is a labyrinth of words, and the reader gets lost in Kafka’s verbal labyrinth where he conceives of another Abraham, for his archetypal protagonist is always an other, going forth to spread words, seeds, deeds. Kafka’s iconoclast wanders in sacrificial words: “Abraham’s spiritual poverty and the inertia of this poverty are an asset, they make concentration easier for him, or, even more, they are concentration already.” Kafka’s tubercular mind and body concentrate within constrictions of a linguistic labyrinth waiting to be expelled and exiled across ancient, modern, and postmodern terrain. His other Abraham is concentric as centripetal forces push him inward, while centrifugal forces of fate compel his wandering destinies and destinations. After his moving inertia, “Abraham falls victim to the following illusion: he cannot stand the uniformity of this world.” If poverty and uniformity plague him, then he must confront diversity in Diaspora.

The narrator then enters Abraham’s labyrinthine sentence with a displacement of identities from concentration to conception – “I could conceive of another Abraham for myself --.” This self-reflexive statement is further elaborated after the dash, as the labyrinth digresses: “he certainly would have never gotten to be a patriarch or even an old-clothes dealer.” Biblical character, always a Hebraic forefather, metamorphoses into Yiddish peddler exchanging old clothes in a new world. Abraham’s disguises unfold in the rest of the sentence: “who was prepared to satisfy the demand for a sacrifice immediately, with the promptness of a waiter, but was unable to bring it off because he could not get away, being indispensable;” Once again, a transition from biblical crisis to comic waiter, lowly server instead of God’s servant. Kafka domesticates his grand, great father: “the household needed him, there was perpetually something or other to put in order, the house was never ready;” Kafka collapses order and otherness in the relationship between father and son, the perpetual ordering from Genesis updated to a modern house that returns uncannily to its archetypal inhabitant: “for without having his house ready, without having something to fall back on, he could not leave.” Cixous would push Abraham out of his house towards a conundrum of going forth, while for Klein he is “A prowler in the mansion of my blood!” There is no getting around these uncanny re-con-figurations.

Cixous and Derrida would make the Kierkegaardian leap of faith to set him in motion: “he had everything to start with, was brought up to it from childhood – I can’t see the leap.” The old story not worth discussing any longer continues to be discussed from the start. Does the narrator have faulty vision from “taking a handful of world and looking at it closely”? Kafka’s parable may not be “logical” and may require an interpretative leap to advance from abstract expressionism to sensible meaning. He establishes a community of Abrahams: “It was different for the other Abrahams, who stood in the houses they were building and suddenly had to go up on Mount Moriah; it is possible that they did not even have a son, yet already had to sacrifice him.” From Moriah to Mount Royal, a polysemous, tragicomic tribe of Abrahams: “These are impossibilities, and Sarah was right to laugh” at these men who hide their faces in “magic trilogies” in order not to see the mountain standing in the distance.

From this absurdity of nervous laughter, the final paragraph turns to “another Abraham” – this one an ugly old man with a dirty youngster as his son. His identity in question, Abraham is concerned that he would change on the way into Don Quixote, another comic wanderer “afraid that the world would laugh itself to death at the sight of him.” These picaresque identities mysteriously and abruptly turn to a classroom with more laughter when the worst student from his dirty desk at the back comes forward to accept an award meant for the best student. Dirty Isaac and dirty student have the last laugh in their sacrificial displacements. Kafka confounds first and last rows, first and last Abrahams, and first and subsequent scrolls.

If Klein’s Montreal affords one entry into Canadian-Jewish literature, then Adele Wiseman’s Winnipeg provides another. In 1949, Wiseman wrote her honour’s B.A. dissertation on Kafka for the University of Manitoba. In “The Kafka Cosmos: An Investigation,” she investigates his ambiguities, symbols, structure, musical rhythms, emotions, and tension within his father-son relationship. Her dissertation is interesting not only for its insights into Kafka’s fiction, but also in the ways it informs her own writing in her first novel, The Sacrifice (1956). Abraham, the protagonist, arrives by train with his wife Sarah and son Isaac to an unnamed city (Winnipeg) in the middle of Canada in a scene that echoes Kafka’s Amerika and The Castle. This tragicomic epic begins in medias res: “The train was beginning to slow down again, and Abraham noticed lights in the distance.” Strongly influenced by Wiseman, Anne Michaels explores the phenomenology of train rides through her dialogue with John Berger in Railtracks: “All great train stations are monuments to the most personal rites of passage and huge historic events – every form of leave-taking and arrival. Mass human displacements, waves of immigration, war, forced migration. Exile, dispossession, exodus, deportation.” Pogroms have forced Abraham and his family out of Ukraine, while the cattle cars of Europe form another backdrop in the novel during the Shoah. The train of transplanting is also the site of trauma. Pogroms, the Holocaust, Abraham’s self-sacrifice, and fires in the synagogue ignite and inflame the burning bush garden.

Locomotion is transferred to Abraham’s and Isaac’s body: “He shifted his body only slightly so as not to disturb the boy, and sank back into the familiar pattern of throbbing aches inflicted by the wheels below.” What is inflicted is also inflected in aural and visual patterns and rhythms of migration. The narrator captures the atmosphere in her movement from lights in the distance to lighting within the train: “A dim glow from the corridor outlined the other figures in the day coach as they slept, sprawled in attitudes of discomfort and fatigue.” In this twilight zone, the protagonist tries to focus on his predicament: “He tried to close his eyes and lose himself in the thick, dream-crowded stillness, but his eyelids, prickly with weariness, sprang open again.” Abraham is as vigilant as the narrator who attempts to limn his precarious state of mind. Dream-crowded stillness and action infuse the novel until its climax when Abraham sacrifices Laiah instead of Isaac. Like Miriam Waddington, Adele Wiseman was also a social worker, and her empathy, insights, and psychological penetration are evident in the creation of her characters.

Sur-nameless, the archetypal wanderer who has been travelling for an eternity of fifteen months and eleven days arrives in the midst of a vast land and Diaspora. “Abraham’s wife seemed to seize the same wailful note and draw it out plaintively as she sighed in her sleep.” Their note interacts with the sound of the train echoing pogroms from the past and their post-traumatic lives ahead: “The whistle howled again, the carriage jolted, and his son lurched heavily, almost lifelessly against him.” The family’s fate is foreshadowed in these opening paragraphs. Wiseman’s train may be filled with Yiddish nuance and inflection from Abraham’s exclaimed “Enough!” (Yiddish genug and Hebrew dayeinu) to his failed attempts to communicate with the conductor in Ukrainian, Polish, and German. He is in need of a translator. In structural symmetry, an interpreter does appear near the end of the novel after Abraham has committed his crime. “The interpreter repeated his question in Yiddish.” If there is a Kafkaesque quality to Abraham’s trial and judgment, the final sentence returns to Cixous’ maternal line and Karen Shenfeld’s “My Father’s Hands Spoke in Yiddish: “With a gesture that was vaguely reminiscent of his grandfather of another time, Moses lifted his hand away from his face, straightened up in his seat, and looked curiously about him at his fellow men.” Another Abraham belongs to another time, as Moses descends from Mad Mountain with tablets of empathy and understanding. Just as Mad Mountain is superimposed on the city along with Moriah, Sinai, and Mount Royal, so Abraham’s family is layered through the Bible, Kafka’s “Abraham,” and Abraham Moses Klein. Similarly, Wiseman’s English resonates with Yiddish and Hebrew rhythms and intonation.

Abraham’s final word to the conductor is “shalom” as he leaves the train. Railtracks and rootprints converge: “perhaps someday even to set down a few roots – those roots, pre-numbed and shallow, of the often uprooted.” Even more pronounced is the word “bundle” in the novel. “Isaac shifted his bundle uncomfortably under curious stares.” This portable burden of concentrated belongings recurs when Isaac finds work in a sweatshop stitching scraps of cloth: “Another bundle. Was this what he was made for?” This leads to a cacophony in the factory: “They were fighting over bundles again. When you finished a bundle you went to the foreman’s table and he gave you another. If he liked you he gave you a bundle…. Two girls had grabbed the same bundle…. Bella screamed that Jenny already had three bundles hidden in her machine…. The girls pulled at the bundle.” This comic scene forms part of the tragicomedy, but the final appearance is much closer to the tragic mode as Moses and his mother Ruth leave their premises: “Moses helped to uproot the furniture…. he came out on the porch with another bundle.” If one listens to Wiseman, the word resonates across a Yiddish spectrum: it hints at the binding of Isaac and at the “Bund” or labour union for which Wiseman’s sympathies are evident. Her fiction bundles the social satire of Jane Austen and caricature of Charles Dickens with the Yiddish equivalents of Shalom Aleichem and Y.L. Peretz. Minor characters such as landlady Mrs. Plopler give rise to the comedy surrounding her name and nose.

Wiseman’s nuances and inflections, gestures and gesticulations, ambidextrous bilingualism, middlebrow irony dancing between low comedy and high tragedy, root cellars and Chagallian rooftops continue to resonate across the Canadian-Jewish landscape. Counter-mythologies of the burning bush garden respond to Northrop Frye’s Canadian paradigm in sacrifices or Qorbanot; the eternal flame or ner tamid situated above a synagogue’s ark; Oif’n Priperchik, the Yiddish melody about the heat of the hearth that Leonard Cohen uses alongside his Hebraic “who by fire”; ceremonial candles of the Menorah; and rescue of the Torah from fire in Mordecai Richler’s Son of a Smaller Hero (published a year before Wiseman’s novel). Eventually Wiseman left Winnipeg for Montreal where Klein’s “roll Ecossic” meets “A parchemin roll of saecular exploit” in the archaic roll call of scrolls, routes, and multilingual sparks.

Anne Michaels has inherited this legacy from both Klein and Wiseman. Her first novel, Fugitive Pieces, opens with “The wall filled with smoke. I struggled out and stared while the air caught fire.” Her young, traumatized narrator watches the spread of “darkness turn to purple-orange light above the town; the colour of flesh transforming to spirit.” Yet another metamorphosis in the burning bush garden.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

This review arrived in my inbox as I was busy typing about an arsonist and a barn burning. It was so all over the place interesting I decided it was an omen and ordering it was a foregone conclusion. And Bachelard is always interesting.