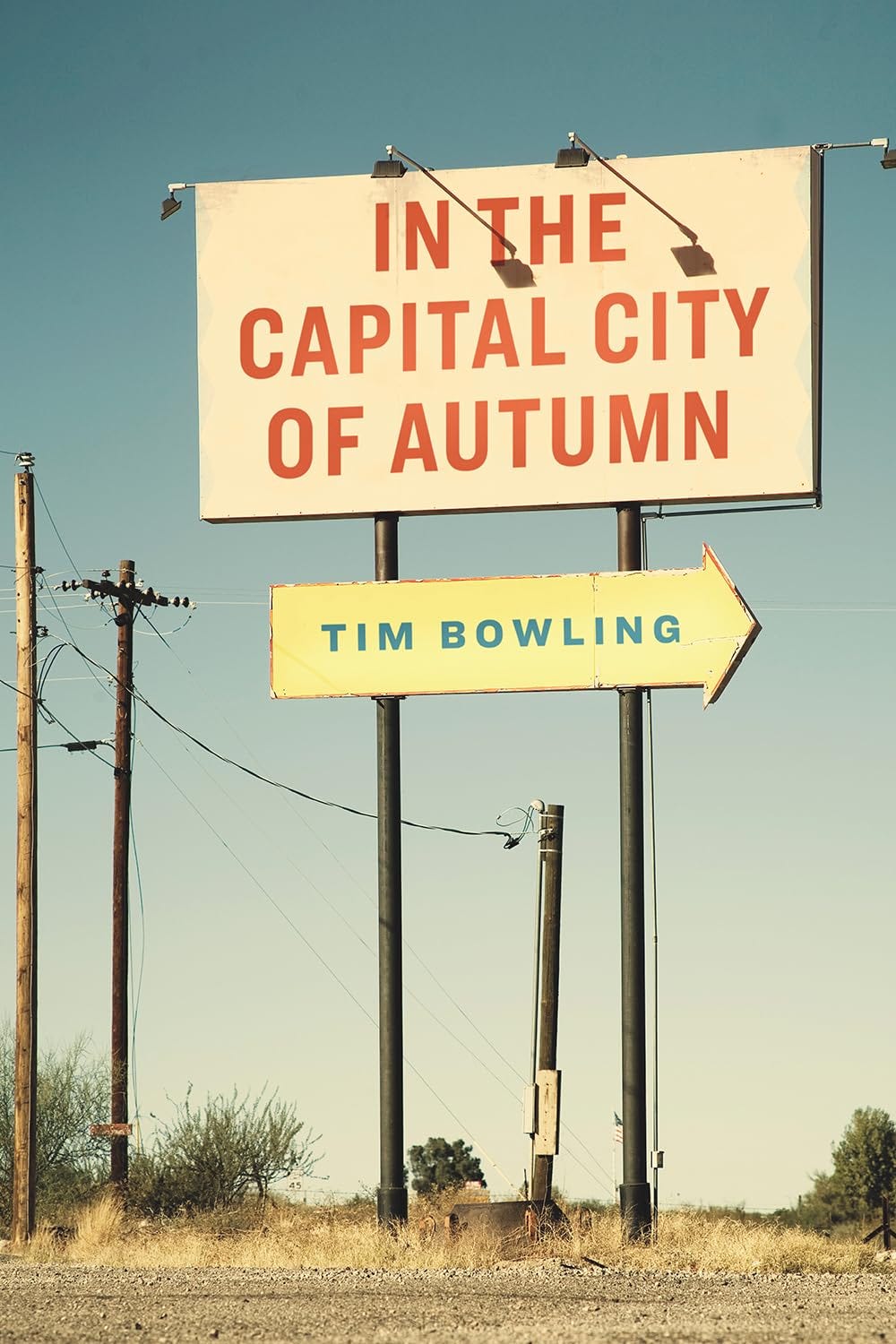

In The Capital City of Autumn by Tim Bowling

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

From the Elizabethans to the Romantics and Modernists, Tim Bowling swallows centuries in his latest collection of poems, In The Capital City of Autumn. The second part of his book looks back exactly 100 years to The Great Gatsby, while his titular poem returns to Keats’s ode “To Autumn,” two hundred years ago. Bowling’s ode repeats the refrain “In the capital city of autumn” at the beginning of each stanza to measure time, for Ottawa’s displacement to autumn is part of a larger pattern of shifting place to time. Between spring’s renewal and autumnal melancholy, he seasons his yesteryears and ancestry in the fall of life.

In his autumnal city “streets glisten like the skin of windfall pear,” but streets also listen to the assonance of autumn in fall, internal rhyme of skin with glisten, and all the l’s that follow: “and taxis languorous as drunken drones on the hive’s lip / let off their fares at abandoned hotels / whose lobby doors close as they open.” Bowling also measures his time-space continuum through alternations between narrow similes and widening metaphors with their stretched comparisons. Fruitful skin turns to animal taxidermy in the drones stretched out in the long, languorous line. Off-season hotels open and close like the hive’s lips and taxis’ doors in emptiness and fullness.

After that long sentence a shorter statement lands in the middle of the stanza: “I was born here.” Borne to city and stanza, carried in taxi and other conveyances. Here belongs to time more than space, which creates an almost surreal atmosphere in urban autumn: “The leaves fall, the sun sets, the tide ebbs …” The season is measured in a daily flow of the quotidian: “Newsboys whisper day-old daily news” against morning shouting. In an aftermath, the diminution of oxygen runs through the stanza’s closing lines: “glassblowers are always out of breath / dogs are an hour away from being stray / and all the typewriter ribbons need changing.” The ebb of breath and dog’s hour are part of the season’s signs, while fading typewriter ribbons also fall.

The second stanza stretches metaphor and clips it into simile: “the moon’s an egg in the pocket of a running thief -- / it trembles like the last tear in a child’s eye before sleep.” After the initial sunset, the moon takes over as a time stealer, the long e in thief running to tear and sleep; its comparison to an egg shrinks and lightens to tear. But it is also a mirror reflecting the poet’s self: “I was that child, am that thief, / stealing what all my neighbours steal -- / the hour hand on the town clock.” The season is timed in the hour hand, dogs’ hour, glassblowers’ breath, and typewriter ribbons. “We always get caught / and write letters of apology with goose quill pens from prison / to the future that is already past. Clockwork inevitably imprisons us, even as we return in lines from typewriter ribbons to goose quill pens, “by the time our postal service of dray horses / and forgetful authors delivers the saddlebags of mail.” The quaint quill rescues history, but we are always caught by the clock. “In any case, we’re soon released / like goldfish from bowls that shatter in transit over bodies of water.” Like Bowling’s bowl, case plays on various containers leading up to this stanza’s conclusion, just as transit picks up taxis and dray horses across the autumnal city. Remember the forgetful authors who change their ribbons and rhythm.

In the third stanza the speaker removes drab suits from scarecrows and dresses snowmen in preparation for the next season. The hour hand on the town clock changes to the “hand making the tape measures the tailors use / to outfit the anonymous lonely for their meeting / with the tall grass outside the home run fence of the ball diamond.” In this landscape, graveyard meets baseball field where the home run rounds the bases from the running thief who steals bases and the capital’s clock hand. Bowling’s clock turns to “happy hour” which “is more complex than you can imagine.” Time flies as do tropes in this season of stanzas. “Together we all lift the needle off the dusty groove / of the spinning vinyl of the season.” In a mood of resignation, earlier work, which “involves dusting the eyelashes / of the sad people in unframed oil portraits,” turns to the labour of lifting the needle off the dusty groove and eventually the “sun’s sawdust” of destiny. The earlier goldfish bowls that shatter in transit over bodies of water become “the old octopus tank / of the aquarium,” where our tentacles reach and flail.

The poet welcomes us to the city of no returns “where the public square holds rallies for solitude / that no one attends.” Emptiness builds from the earlier bowls that shatter “in transit” to “Here is your transit pass to the direction of the rain / and a journal in which to sketch the faces of the first people / to tie your shoes before their smiles dissolve to spiderwebs.” The ghostlike ending attaches smiles to familiar parents: “The fog’s come. And two ships in it / like the figures of my parents. I have to go. / Please return my life of tender purpose to its memory.” Rain’s direction tilts from streets that glisten to a figured fog politely sketched in the capital city of autumn, which undergoes its own rite of passage.

The book’s opening poem, “Yesteryears,” layers history in a glide of typewriter tropes. We begin in Vancouver: “Took the fat family bible and tossed it / off the Lion’s Gate Bridge.” The bible is overweight because it is filled with history sunk between alliterations of fat family encased within took and tossed. In the silt of centuries and personal history, we drown further in underwater f’s: “Goodbye Toronto pre-Depression infant death. / So long psalms of Edwardian fiscal failure.” After the alliteration of Depression death, the long o’s of “So long psalms” open and close the sunken bible. The poet then shifts from the Canadian scene to England in a historic comparison, and from end stops to enjambment. “Hurled it the same as Cobden-Sanderson / into the Thames his blocks of type / so no one could come after / so no one could traffick in his lonely fight.” Bowling tosses in Cobden-Anderson (a bookbinder associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement) to parallel his own actions. A period that should appear after “fight” disappears with his blocks of type, with only Bowling to follow in his shoes. Blocked and cast into water, he bids “Good riddance to fleshpress and letterpress / the antiquarian appetites of every cast.”

Floating and sinking, weightlessness and heaviness work through the lines: “let the orca swallow the bile anvil / for a fibrillating sponge.” The weight of the bile anvil recalls the fat bible, as fleshpress and appetites work through his system. The sonic river carries “a fibrillating sponge / and sound so deep,” so that the poet will never hear the undertaker’s step or midwife’s swaddling another corpse. A sinking sentiment and sediment: “Limit the edition / to a run of naught.” Gothic nothingness heads downwards, “Dropped like a gargoyle cracked / by revolution off a parapet.” Corpse and undertaker lead to an undertow of “Dead weight of words and font / a typewriter not typed with / since the ceasefire of the Second War.” In this surrealistic world with strained syntax and one black eye for the sun, the orca turns to “the cage with a dead shark / clamped to a dead limb / the bone lifted from under the skin/ future’s twin.” Bowling’s threnody drops into the western bay and marauding tide, and tests the remorseless deep beneath the watery floor.

His bible gets tossed into “Ancestry” and “In the Beginning.” Salmon swim downriver through many of the poems, reminders of his beginnings in British Columbia. In “Encore” he feels the “downward pull of that weight” and sees a small man “dangling a forty-pound salmon under the gill.” In the dark light of a streetlamp, “Human eyelids flutter over the blank of the salmon’s black look.” Instead of fish flutter, he offers human vision “into the sharp ache of my dull sleep.” In “Apprentice” the poet lights out for the west, like Huck Finn, “to where the sockeye built.” Salmon fins and sock eyes participate in a dialectic with the drowning typewriter. On the one hand, the poet “plucked the black thread / of a typewriter;” on the other, “Dead, the salmon pressed their / silent laughter to the cracked / linoleum.” A synthesis of the two: “I struck and struck / each key each black and / gazeless eye.” In the twinned trope, “I heard / the knock in the salmon’s stilled heart,” even as he tries to hold the pastels in place on the school paper. An apprenticeship with schools of fish, paper pastels, and the typewriter’s carriage return. The typewriter is the bait and weight of Bowling’s craft, its ribbon the line that lures poem and fish.

His wistful gaze reappears in “In Ladner Harbour” where he looks longingly towards his past with his father in filial lines. A lapping of water appears in the rhythm between poetic line and sentence: “I went and sat by my father’s old moorage spot.” Instead of the weeping of exile by a historic river (which appears mid-stanza “as a man cries”) the two simple verbs anchor past and present in this spot of time. Time’s ripple skims the next sentence’s lines: “My eyes of frayed stern-rope / my skin of planks / changing colour with the weather.” Stern because of the backward glance, the reversal of sk and ks in skin and planks, and the internal rhyme of colour with weather – echoing Ladner Harbour. Negatives in the next two sentences attest to emptiness: “No boats passed / except the leaky vessel of childhood / that sinks a little lower / every time we look at it.” Bowling’s sinking occurs in the leakage of mood and metaphor, aligned with time’s transference and the anagram of sink and skin.

The next negative elongates the sentence, finely balancing each line: “No fog, but the foghorn sounded / out where the fresh meets the brine / as a man cries (silently) / between the salt in his blood / and his mother’s milk.” The doleful net of long o’s yields to long i’s in brine, cries, silently to accelerate the loss. This meeting between salt water and sweet is elaborated in the next sentence as scene and mood unfold. “The river’s handshake with the ocean / mine with Time / the clasp and unclasp / my father’s grip / I can almost touch it / a branch in the fog.” The hush of fog in the “sh” of handshake and ocean is a fulcrum for the foghorn that concludes the stanza. Long i’s in mine time alternate with short in firm grip to mark the initial mooring spot of time.

The concluding stanza is a single sentence that paints the long look of personal history through the poet’s frayed eyes:

“Look long where I look: the grey sky in the grey water for miles and the single nailhead of a risen seal that holds the halves of the world and a life together.”

Exchanging colours of colourlessness, the poem contrasts the risen seal (a form of resurrection with its nailhead) with the earlier sinking vessel, a severed world reunited in harboured elegy of clasping tides.

Bowling boats backwards in “The Great Gatsby Poems,” shifting from personal history towards a recreation of Fitzgerald’s characters. His autumnal mood alternates with uplifting colours. The first poem in this series, “University,” introduces the novel’s major characters as the poet interacts with them. “Once I was younger than Gatsby and Nick. / Now I’m older than Wolfsheim.” An awareness of aging continues in the next sentence: “My professors are all retired or dead.” Only to be revived in these poems’ fusion of Fitzgerald:

“But coming again to Fitzgerald’s final page

fresh as one of his hero’s beautiful shirts

I take off my glasses at my own funeral

and, wiping them, whisper, “The lucky son of a bitch.”

The finality of a resurrection requires lens cleaning in the adjustment of perspective in life and death.

Bowling’s wide-ranging inventiveness is on full display in each of his pointed portrayals of Fitzgerald’s characters from trivial (Ewing, Klipspringer, the butler, cub reporter and boy with brick) to central. “Ewing” stretches out a couple of sentences like an albino bat hidden in the wings of a house of fiction: “Maybe because he was so shy / living in that mansion / like an albino bat / Fitzgerald gave him a flight name / East Wing of the White House / some further if subconscious nod / to the listlessness of the republic / ‘I was asleep. That is, I’d been asleep’.” The next sentence (and stanza) encapsulates the trivial actor from bat to blood across Broadway and Greenwich to an elongated exclamation: “—nevertheless today the most famous of all the Klipspringers!” Clipped bat, glasses, gloom, fingers and wing spring to the conclusion.

“Final Guest” bookends the sequence with “The party’s not over / until we are” – coming again to Fitzgerald’s final page. The series begins with the speaker wiping his glasses to clarify the centenary of Fitzgerald’s novel, and ends with “Kill the beams” for enacting stagecraft. From the first “fresh as one of his hero’s beautiful shirts” to the last “silky / as the shirts on his bed,” the poet takes away meaning from the novel: “that’s the experience of literature -- / a great book’s the lovers’ lane / we drive to alone.” The literary qualities of wonder, tragedy, loss of illusion, and pain are part of the old sport’s reading experience. And Gatsby – “he spooned only / with the self, the self’s dream –”, his ego trapped between dashes, like a bat in headlights.

“After Reading King Lear Again” revisits Shakespeare: “It’s spring, the antiquarian bookseller’s day off / from eccentric dust and endless / appraisals of worthless bibles --.” Sibilance accumulates through dust from season to day, as the poet appraises Shakespeare’s sources and offspring: “we’re all waiting / for the cast party for the cast / of Waiting for Godot / to get going.” The poet casts his line of repetition. “Spring. Just.” – seeking justice for dramatic encounters with Beckett’s absurdities. “Five ladies lift their skirts and stand / on chairs at the edges of cliffs / and shriek, ‘Eek! Eek! Lemmings’!” Ladies on the heath imitate the animals and Lear’s daughters; they lift before the potential fall from cliffs.

The second stanza further sketches the season: “Spring – time to write odes to the ides” – a move from edges to middle of month. The gaze begins with the familiar but turns eccentric: “I spy through my neighbour’s open door / his wife blooming daffodils / in a sizzling pan.” The poet pans from frying flowers to “over the rooftops” that recalls the cliff’s height. Spring is thus a springboard for writing odes, ides, and Shakespearean tragedy, a platform for (dis)appearance: “the Etch A Sketching waxwings / erase themselves and reappear” to answer the lemmings’ shriek. In the valley beneath cliffs “a coyote loosens / the cravat in a rabbit’s throat.” Like the earlier lift, this loosening is deadly. An unknown child addresses the poet as if it’s 1934, and the poet looks “at the chalk beams of his architecture / as if it’s 1664.” This slide back through history is matched by a sideways glance in space: the poet’s spying and look lead to his “eye-sands” in the scientific and political landscape.

In the final spring, divorced parents get back together, the cancerous dog “uncancers” and leaps like lemmings. Any rebirth is fraught: “all of us, like the a / in aria, begin and / end and end and.” In this oscillating alphabet, the shifting of vowels from odes to ides, the Etch A Sketch, and the aria that begins and ends in a cycle, letter Bowling’s re-reading until the final plunge: “The sun / the lonely planet in his arms / goes down.” From dawn to down the poet has years on his back.

In the final section of the book, Bowling laments the loss of his dog, and in his final poem, “The Exit,” he buries the canine and his own collection with a tight alignment of creature and craft. “Come into animal presence, the poet writes.” He balances bodies of pet and poetry. “Reconnect and resurrect.” An array of personal pronouns surrounds the dead body, giving it life while removing life: “But when you enter, you must also leave. / I close the door on her bones and every text.” The leave taking adjusts the trope of leaves in the book.

In the second stanza a cosmic-domestic metaphor plays into the intensity of identity between creatures:

“Ladle of a constellation in the cold black broth.

A valley away a coyote scents my rising breath.

I am my own animal in a human lair.”

Between ladle and lair, the near rhyme of broth and breath matches resurrect and text in the first stanza, even as rising returns to resurrect. Their interconnection appears in the almost palindromic sounds of “am my own animal.”

The third stanza repeats “Come into any presence now” before turning to “blind” imagery. The final stanza picks up the earlier constellation, elongating e’s and contracting r’s:

“Out here the stars

like baby teeth in a grave

never really disappear.”

Hear the here through a scope, darkly: an apotheosis and a fitting departure from spring to fall.

About the Author

Tim Bowling is the author of twenty-four works of fiction, nonfiction and poetry. He is the recipient of numerous honours, including two Edmonton Artists’ Trust Fund Awards, five Alberta Book Awards, a Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Medal, two Writers’ Trust of Canada nominations, two Governor General’s Award nominations and a Guggenheim Fellowship in recognition of his entire body of work.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Buckrider Books (Wolsak & Wynn, April 16 2024)

Language : English

Paperback : 88 pages

ISBN-10 : 1989496865

ISBN-13 : 978-1989496862