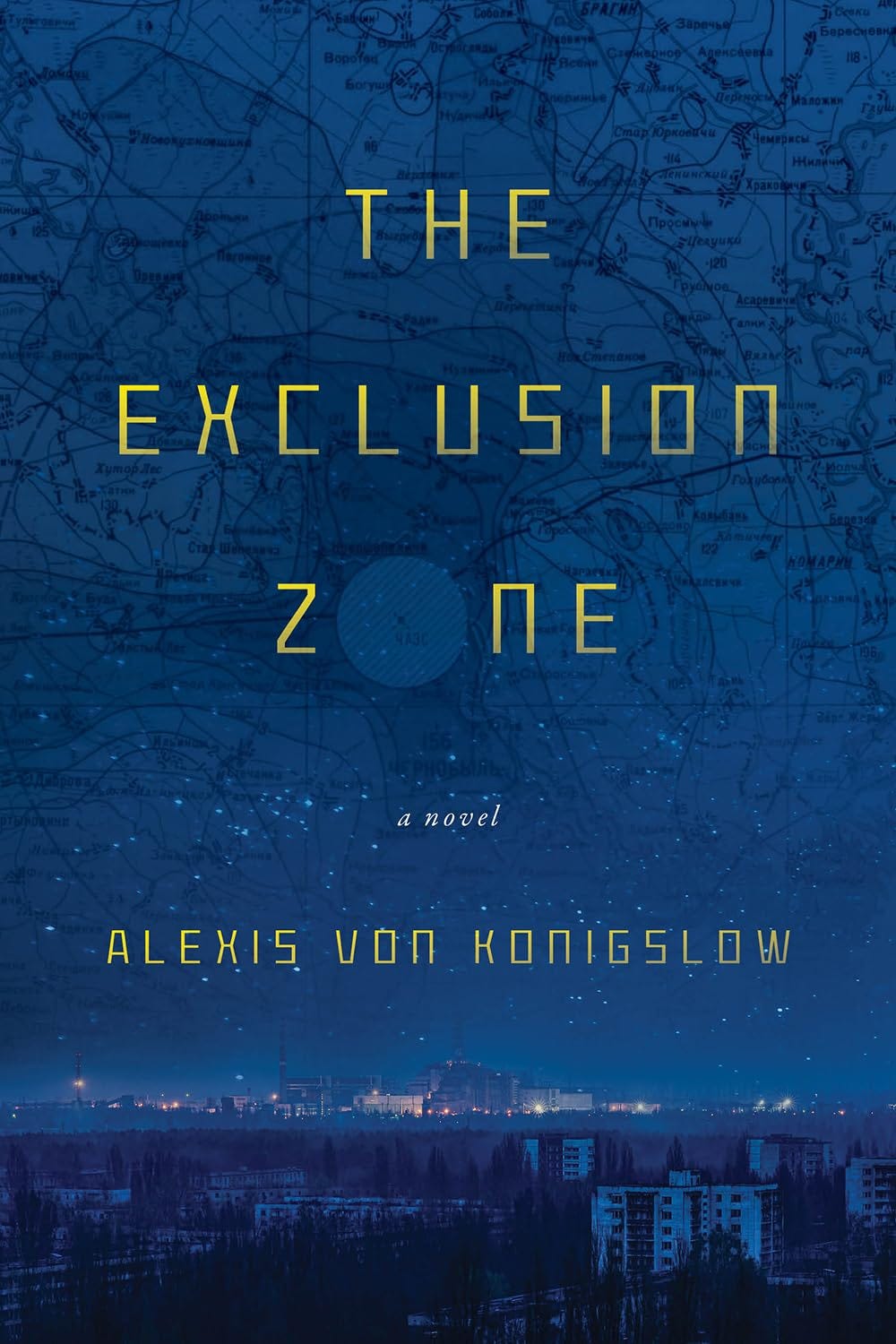

The Exclusion Zone by Alexis Von Konigslow

Reviewed by Emily Weedon

Alexis Von Konigslow’s novel The Exclusion Zone takes readers to the blighted area of Chernobyl, in the much-studied aftermath of the nuclear disaster which up heaved hundreds of thousands and rerouted history for plants, animals, humans, and governments. It could have been even worse. The disaster is one of the most defining testaments to the ability of humans to wreak havoc on themselves, and to meet the challenge, albeit after damage has been done, to rally heroically to try to stem worse effects. The site remains, mothballed and relatively deserted years later, leaving behind a freakish monument in time, a museum of staggering liminal spaces which are of course catnip to thrill seekers and danger tourists. Vice Magazine famously reported about the site on a vodka-soaked tour: vodka was erroneously touted as a safeguard. File that under drinking Windex is good for Covid. It is understandable that 40 years on, the site is as fascinating as it is dangerous and mysterious, and therefore a promising setting for a novel.

Konigslow’s main character Reyna is a scientist who has travelled from Toronto to Chernobyl to work on a study about datasets and fear, to create a program trained to recognize fear. At the same time, the scientist, who is a woman, is running away from a troubled marriage, is the daughter of a famous scientist and despite her cred and her own awareness that she knows her stuff, she suffers bouts of imposter syndrome, the ribbing and frank derision of her male counterparts and her own husband.

Much time in the novel is spent wandering the forest and wandering through her own anxious thoughts. Photos of technicians who were working the reactor at the moment of the explosion are studied with the reserve and remove of a lab scientist studying effects on lab rats — all the drama of the event itself is removed, and much time is spent circling muscle groups on faces which are “broadcasting fear”. I found the reiterative descriptions of fear became tedious. And the purpose of a program to recognize fear in human faces — presumably before humans do — seems to be of questionable utility. The people at Chernobyl didn’t need to read fear more quickly. Human error and possibly hubris were involved in missteps which led to a catastrophic failure of fail safes. They needed to build a better reactor and run it more carefully.

So ruminant are the thoughts of our main character scientist that I would argue the work is more plotless fiction than thriller. While I respect that Konigslow delves into the extra labour that women still must do to be listened to, heard, understood and respected for their contributions, I found myself wishing that the science the scientist was doing was harder, more data driven. As it is, the device of sifting and scrolling through photos of people who lived through the disaster felt soft. I found prose and plot were likewise unclear and meandering. Konigslow hints at plot, rather than crisply situating readers and driving the plot along, as readers of a thriller voraciously demand.

I recently watched the excellent series “Chernobyl” while reading the book. Where plot, goal and drive are muted in The Exclusion Zone in favour of ruminant thoughts, “Chernobyl” drives plot relentlessly as the protagonists are forced to act in an epic struggle to stave off worse disaster while staring down fallout that could poison the earth for 24,000 years. Even then, the teleplay is less about the reactor disaster at Chernobyl than it is an exploration of the fallout of lies and hubris, and the way that the truth will out.

Of course, not all the stories are wrought on such a scale. Each blade of grass, moth, bird, deer, and human that was affected was just some organism trying to live its life. Konigslow’s meditative foray into the liminal is one more tile in a massive mosaic exploring the catastrophe of Chernobyl. The Exclusion Zone consciously evokes climate change, reminding us, as we continually are these days by news and art alike, that we live in the Anthropocene — the era formed by the folly of humankind.

About the Author

Alexis von Konigslow is the author of The Capacity for Infinite Happiness. She has degrees in mathematical physics from Queen’s University and creative writing from the University of Guelph. She lives in Toronto with her family.

About the Reviewer

Emily Weedon is a CSA award-winning screenwriter and author of the dystopian debut Autokrator, with Cormorant Books. Her forthcoming novel Hemo Sapiens will be published in September 2025, with Dundurn Press. https://emilyweedon.com/

Book Details

Publisher : Buckrider Books

Publication date : May 20 2025

Language : English

Print length : 224 pages

ISBN-10 : 1998408167

ISBN-13 : 978-1998408160