The Knowing by Tanya Talaga

Reviewed by Anne Smith-Nochasak

“Listen carefully to the voices that come to you from the place before memories are remembered. “Every sound, every beat, has a purpose, a meaning. Everything reverberates: it is heard and it lives, never leaving space and time.” --Tanya Talaga, The Knowing (p. 402)

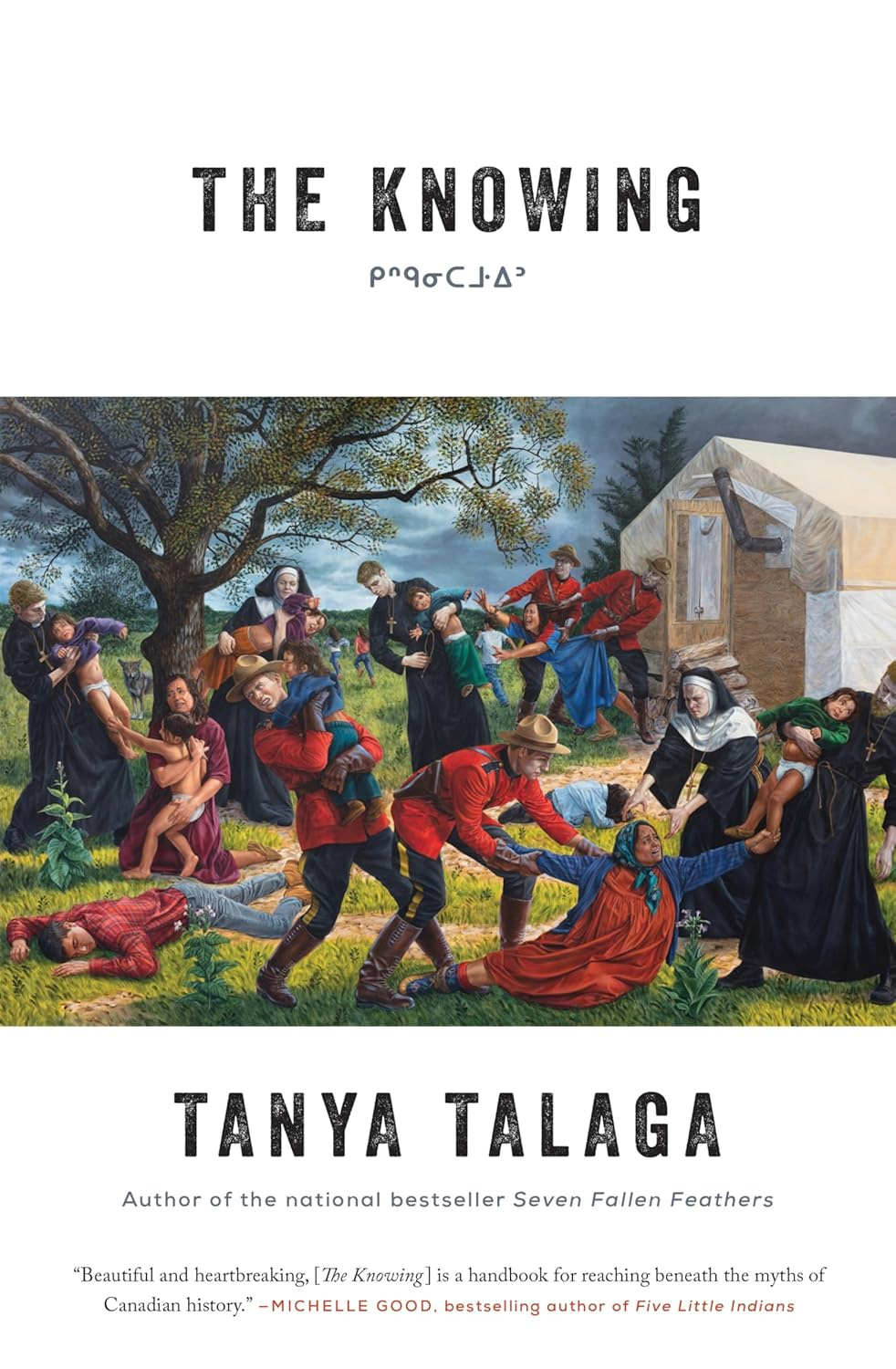

“The Knowing” refers to the collected knowledge that Indigenous people have carried through the generations: the awareness of a genocide systematically perpetrated and denied by church and state. Tanya Talaga’s book on the subject begins with the discovery of the undocumented graves at the site of the Kamloops Residential School and carries us through the history of contact—the social and political machinations that shaped and shaded history, and the struggles of Truth and Reconciliation to go past perfunctory apologies towards a true way of being. Woven into it are the personal stories of those who have carried this unrecognized truth. Although she shares “the Knowing” with journalistic thoroughness and documentation, she especially presents it with humanity. She brings the story to life in heartbreaking, deeply personal prose.

The residential schools are scrupulously documented in terms of location, funding, leadership, and social implications for Indigenous communities. The facts, though, are presented with grace and compassion, honouring the little stories within, linking them to her story, linking all stories. We feel for the parent who is denied a voice in their child’s life, the parent who never sees or hears of their child again. We weep for the child bewildered and alone. For the grief carried through the generations, each generation with old and new grief to carry.

Woven into the documentation and the stories she received along the way is the story of her own family, of her quest to find her great-great grandmother. Along the way, she uncovered many losses and discovered many stories not known to her family. Sometimes, people carried truths that they simply could not share. Many times, the documentation provided by church and state was, to say the least, completely inadequate. It would take infinite patience and determination to sort letters, unlabelled photos, “patchwork” recordkeeping, and obscure references, to piece together a history. The heartbreak of discovering a family member previously unknown and then finding no records to lead one further! The grief of finally piecing together the bare bones of her great-great grandmother’s courageous story and finding its sad ending—abandoned, bewildered, and alone. We realize the history on a deeply personal level.

As I read, I took days away from the reading to process and to grieve for the lives lost and uncelebrated by history. Then I returned, for in this book, each life is now honoured and cherished, as it has been in the hearts of those who knew but went unheard.

There are many names to remember in this study, and each name represents a life—a life that passed into anonymity but was a life valued and loved by a parent and is a life valued and loved by a people. Each name has a place in the world.

“She (the author) searches through a fragmented historical record, bringing an order that is disturbing in its revelations, but healing to reveal. She brings order out of a chaos that should not have been. Rage is a most compassionate response.”

A sense of pathos and also of anger permeates the pages. The pathos comes through in the tiny details—such as a letter briefly informing parents that their child had passed away on Sunday. The letter was dated the following Tuesday. The anger is there in her analysis of the mental asylums, in the horrifying details of treatment, in the rejection of any Indigenous perspective on mental wellness, in the poking and prodding and being told, in essence, that they were worthless. It is in descriptions of voiceless little children, tortured and violated and alone. She searches through a fragmented historical record, bringing an order that is disturbing in its revelations, but healing to reveal. She brings order out of a chaos that should not have been. Rage is a most compassionate response.

Yes, this is a very detailed book, and some have argued that it is repetitive. I find the repetition functions more as a refrain, reinforcing and accenting the information as it accumulates.

This history is important to all of us if we are to go forward. Many today will have heard the highlights of the facts, but the way this history is told makes this book outstanding: intense and captivating, this is a book that can shape our way of thinking and transform it, finally, into a way of living.

About the Author

TANYA TALAGA is of Anishinaabe and Polish descent and was born and raised in Toronto. She is a member of Fort William First Nation. Tanya Talaga is the founder of Makwa Creative, a production company formed to elevate Indigenous voices and stories.

About the Reviewer

Anne M. Smith-Nochasak grew up in rural western Nova Scotia, where she currently resides and teaches part-time after many years working in northern communities. She has self-published three novels using the services of Friesen Press: A Canoer of Shorelines (2021), The Ice Widow (2022), and River Faces North (Taggak Journey, Book 1, being released in early September 2024). She is currently a member of the Writers Federation of Nova Scotia. https://www.acanoerofshorelines.com/

Book Details

Publisher : HarperCollins Publishers (Aug. 27 2024)

Language : English

Hardcover : 480 pages

ISBN-10 : 1443467502

ISBN-13 : 978-1443467506