The Posthumous Landscape: Remnants of Jewish Life in Eastern Europe by David Kaufman, with Essays by Bernard Avishai and Joanna Podolska

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Touchstones in Synagogues and Cemeteries

In World of Our Fathers Irving Howe examines Yiddish influences on American Jewish writers, and notes an underlying intonation and rhythm in their novels. In the world of our mothers Goldie Morgantaler translates Chava Rosenfarb’s Montreal Yiddish stories in In the Land of the Postscript. On the cover of that book Jack Beder’s painting Grey Day, Prince Arthur Street (Montreal, 1937) depicts a barren streetscape, an abject side of Jewish immigrant life with a different rhythm and intonation. Some of that spirit informs David Kaufman’s poignant and haunting photographs in The Posthumous Landscape. With traces, shadows, and aura, his camera captures posthumous postscripts of Jewish life in Eastern Europe where picturesque restored synagogues resonate with their counterparts in Montreal and Toronto. Unrestored synagogues and cemeteries, however, tell a different story.

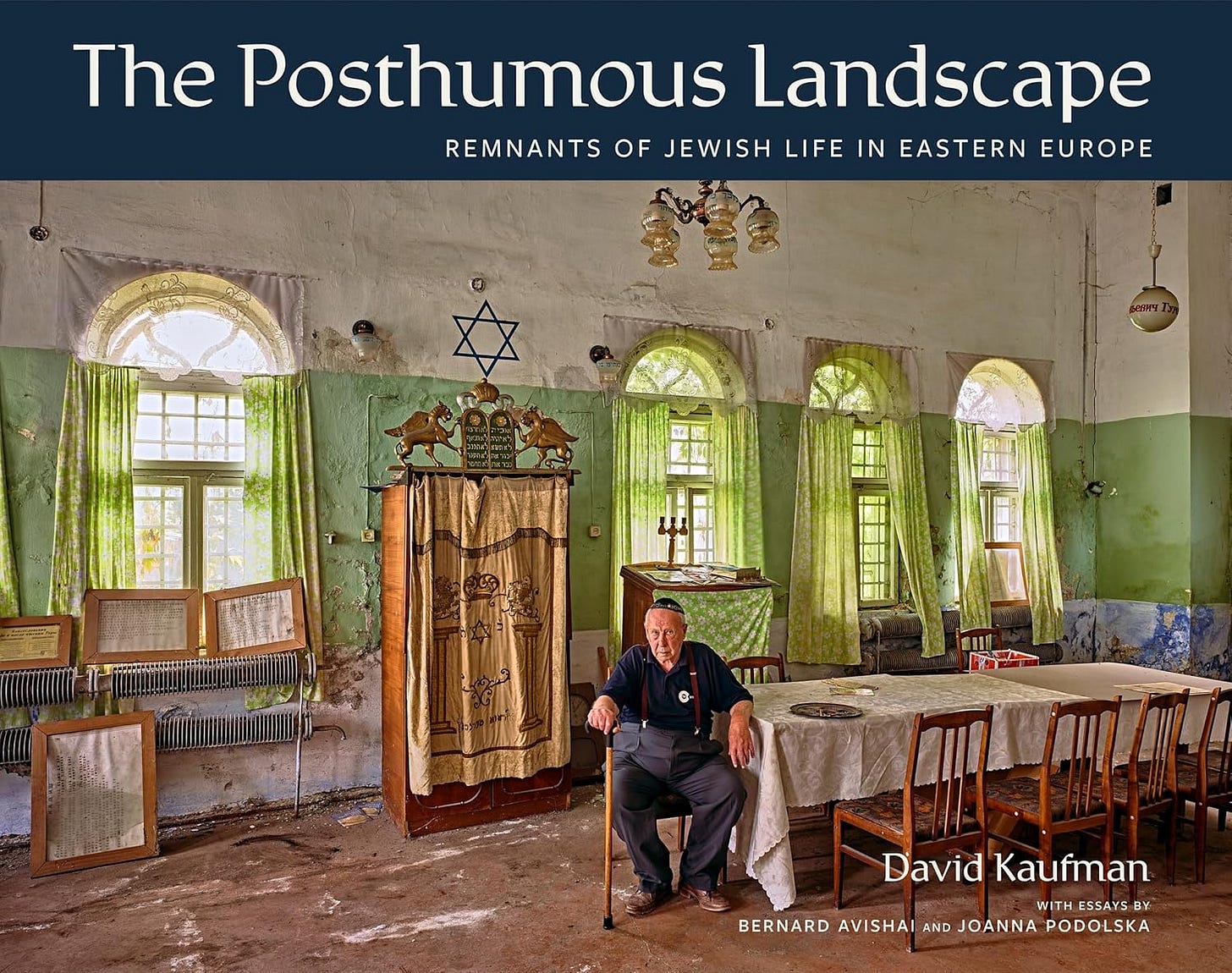

The arresting front cover of the book portrays an elderly man in the postwar synagogue of Khotyn, Ukraine, 2016. The man at the centre, Yurij Davidovich, is seated at the head of a table and further supported by his cane, which may be in dialogue with the photographer’s steadying tripod. Together with his synagogue this quorum of one has aged, both survivors of Europe’s killing wars. A remnant of life in this synagogue, not only is he alone in this photograph, but he is also unique in so far as the vast majority of photos in this book contain no human beings, only empty synagogues, cemeteries, and Holocaust memorials. In a sense, then, Davidovich is the protagonist of this book, sitting front and centre on its cover, an Aron Kodesh or Holy Ark to his right, while his left arm rests on an empty table that had once seen better days. His left hand hangs down, his right clutches the cane, but it is his facial expression that is crucial in limning the mood in his rundown synagogue. His eyes tell the story of torment in every detail of the room. His suspenders are reminders of the absence of a tallit or prayer shawl, which is in turn reflected in the hanging green curtains draped over windows that bring bright light into an otherwise darkened interior of mould and scar.

Those secular curtains contrast with the cloth covering of the Ark, which may or may not contain the Torah Scrolls. In concert with Davidovich’s humble kippa on his head, an embroidered crown on the beige or golden cloth is supported and guarded on either side by winged lions or griffins that are meant to suggest strength. Any aspirational elevation in angels’ wings or phoenix rising is met with the grim reality of a need to flee during pogroms and other forms of persecution. On top of the Ark two carved griffins frame and support tablets with their Ten Commandments. Again, the crown on top meant for majesty, must bow to history’s humiliating forces. The blue Star of David painted immediately above the crown is another emblem of faith and fortitude in the midst of crumbling walls and hierarchies.

These mythical and biblical animals scattered throughout the shuls in the book call to mind Franz Kafka’s eloquent, fanciful parable, “The Animal in the Synagogue.” Kafka’s creature is a marten, at once stationary and in motion, belonging and not belonging, in one particular Czech synagogue yet capable of roaming among many structures across Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, and Latvia that Kaufman has photographed so thoughtfully. Kafka’s mildly iconoclastic allegory animates photographic memories: “In our synagogue there lives an animal about the size of a marten.” In other words, its spirit haunts Kaufman’s empty spaces: “One can often get a very good view of it, for it allows people to approach to a distance of about six feet from it.” From this distance, the photographer notes its pale blue-green colour. “Nobody has ever yet touched its fur, and so nothing can be said about that, and one might also go so far as to assert that the real colour of its coat is unknown, perhaps the colour one sees is only caused by the dust and mortar with which its fur is matted, and indeed the colour does resemble that of the paint inside the synagogue.” Seen through Kafka’s lens, Kaufman’s photographs colour the dust and mortar of spavined martens and crumbling structures, floors scuffed by history, human footsteps, and allegorical animals.

Kafka is prophetic in his vision of the animal’s surroundings, which in turn applies to Kaufman’s own commentary on his photographs. The narrator would try to comfort the marten by telling it that the “congregation in this little town of ours in the mountains is becoming smaller every year and that it is already having trouble in raising money for the upkeep of the synagogue. It is not impossible that before long the synagogue will become a granary.” History follows Kafka’s fable: in town after town across Eastern Europe synagogues were turned into warehouses under the Russians, Soviets, or Nazis. Some of these Jewish communities, such as Lublin, began in the fourteenth century, and subsequently Jews formed either a majority of the shtetl, or a large minority of the population of larger centres.

Traces, shadows, and aura recur in each of the photographs to reveal the history of a building or a cemetery. Kafka’s marten finds company in Kaufman’s griffin: “the curtain of the Ark of the Covenant hangs from a shining brass rod, and this seems to attract the animal.” The animal is sensitive to noise, not only from the praying congregation, but also from external forces such as a pogrom. “And yet there is this terror. Is it the memories of times long past or the premonition of times to come? Does this animal perhaps know more than the three generations of those who are gathered together in the synagogue?” Generations in the lines of a story or gravestones in a cemetery marked without an ending in The Posthumous Landscape. Leaning on and intoning Davidovich, “The beadle of the synagogue says he remembers how his grandfather, who was also a beadle, liked to tell the story. As a small boy his grandfather had frequently heard talk about the impossibility of getting rid of the animal, and so, fired by ambition and being an excellent climber, one bright morning when the whole synagogue, with all its nooks and crannies, lay open in the sunlight, he had sneaked in, armed with a rope, a catapult, and a crookhandled stick. . . .”

The beadle’s crook-handle meets Davidovich’s cane in a moment of ellipsis. Kafka’s open-ended ellipsis in turn meets Joanna Podolska who, along with Bernard Avishai, provides commentary and context for The Posthumous Landscape: “Surely, David Kaufman also heard this loud silence that tells stories, or maybe he heard the echo of the streams still murmuring in Yiddish …” That Yiddish rhythm flows through all of the photographs of synagogues and cemeteries with their angled gravestones tilting alongside tall grasses and trees.

These monuments surround Davidovich’s absent minyan. When asked if there is any tension between Khotyn’s few Jews and their neighbours, he replies: “We have nothing, and they have nothing. What is there to fight about?” Kaufman’s photographs create a life out of that nothingness.

Another photograph features the caretaker’s room in the same synagogue with Hebrew letters around a circular ceiling lamp, and a tallit-like towel draped over a clothes-stand that is in secular dialogue with a hanging religious cloth in a corner of the room.

On a brighter side, several photographs display the splendour of restored synagogues. For instance, on the book’s back cover the synagogue in Lancut, Poland is held up by four ornate columns with biblical animals parading on the walls alongside Hebrew prayers. A solitary prayer shawl draped over a railing, another reminder and witness to history and silence, serves as a fitting bookend to the front cover’s absent tallit. This Baroque brick building was built in 1761. In 1939 the German occupiers tried unsuccessfully to burn it down, though the structure was subsequently used to store grain, as if to fulfill Kafka’s prophecy. On the page opposite the description of Lancut’s history, we find three gravestones in the Jewish cemetery of Bochnia, a small town near Krakow. In April 1941, the Germans established a ghetto in town, then they deported the Jews to death camps at Belzec and Auschwitz. With their marble inserts, extensive calligraphy, lions and crowns, the three gravestones stand as memorials to a long and complex history of Polish Jewry. Many of the stones and bricks were used by the Nazis to pave roadworks. One may turn the page and suddenly be confronted with the crematoria of Majdanek’s concentration camp, or train tracks in Auschwitz-Birkenau where millions were murdered.

Another bittersweet memorial appears in the beautifully restored and refurbished synagogue of Sataniv, Ukraine – a town without Jews, even though Jews had thrived there over centuries under the Kingdom of Poland. A portrait of Uriel Dorfman (1923-2022) shows his grim face knowing that the future for Jews in his Lviv, Ukraine is equally dismal. Equally sad is the portrait of Meylakh Sheykhet, a radical activist and Orthodox Jew in Ukraine. Traces, shadows, and aura in these remnants intone the rhythms of an ancestral world.

An imposing mausoleum of industrialist Israel Poznanski in Lodz, the largest Jewish mausoleum in the world, is a reminder of the success of Polish Jewry during some periods of history. This solitary structure stands in contrast to the majority of cramped gravestones that seem to bow down to gravity amidst swaying undergrowth. Each photograph speaks a thousand words of silent witness; each photograph preserves centuries by composing decomposition. Posthumous reminds us of the “humous” of human and humus of ground and earth in a range from humans to humility, and Adam to Adamah in Hebrew. Look upon these synagogues and cemeteries, bounded and bare, their lone and level bricks and plaster stretching far away. These photographs share thoughts of deeper seclusion, connecting landscape with the quiet of the sky, lonely rooms restored in a tranquility that sees into the life of things. Kaufman’s monumental kaddish belongs on the coffee table alongside Roman Vishniac’s A Vanished World and Frédéric Brenner’s Diaspora.

About the Author

David Kaufman is a Canadian documentary filmmaker and photographer based in Toronto. His photographic work focuses primarily on the architectural image and the urban landscape. His work in Eastern Europe is represented in a traveling exhibition entitled The Posthumous Landscape: Jewish Historical Sites in Poland and Western Ukraine.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature. He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : Figure 1 Publishing

Publication date : Oct. 21 2025

Language : English

Print length : 232 pages

ISBN-10 : 1773272578

ISBN-13 : 978-1773272573