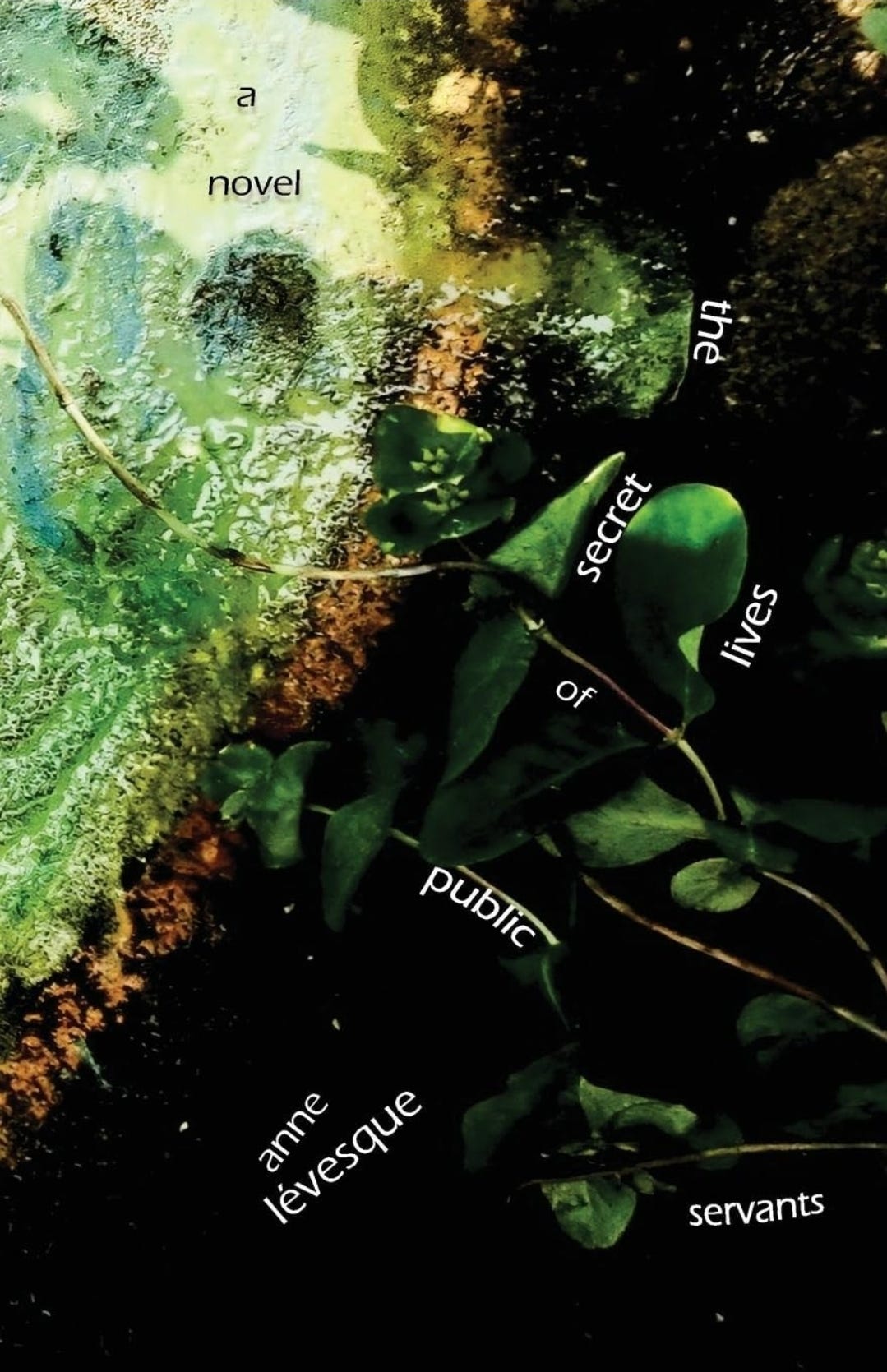

The Secret Lives of Public Servants by Anne Lévesque

Reviewed by Steven Mayoff

To us they’re just the faceless paper pushers, desk jockeys, and number crunchers lurking behind curtains of red tape in grey government offices while living lives of quiet desperation. But to Cape Breton novelist Anne Lévesque, they are multi-faceted humans just like us and worthy of closer examination. In her complex and witty second novel, The Secret Lives of Public Servants (Galleon Books, 2025), Lévesque does just that, training her writer’s microscope on four such denizens.

The novel is centred around Del Charbonneau, a pension clerk and art school graduate, whose own not-so-secret life is spent gathering material for an ambitious art installation that uses office paraphernalia to document the culture of bureaucracy. But her day job has given her a different, if equally absorbing, obsession: tracking down the whereabouts of three Lost Annuitants – Lee Gaik Wah, Stephen Higdon and Caroline Melançon – all of whom have been away from the public sector for decades and have pensions coming to them.

Perhaps being true to the convoluted nature of bureaucracy itself, Lévesque rejects a straight linear narrative for a seemingly-haphazard structure that comes in the form of vignettes that eventually do add up to a larger jigsaw puzzle of a picture. In these vignettes, we learn of Higdon’s time as a forest ranger in a lookout tower, his yoga practice and hippie lifestyle. We get glimpses of Gaik Wah’s life in Taiwan, her relationship with her mother, and her struggles to assimilate into Canadian life which lead to an unsuccessful marriage. Melançon strives to balance her privileged life of being married to a politician with volunteer work feeding the homeless, which result in guilt and self-questioning.

But perhaps the most secret life of all is the actual world of endless protocols, documents, drudgery, camaraderie, rivalries and banal pleasures that make up the public servant’s existence. Lévesque lays all of these out as someone who has most likely been there first-hand, rather than someone who has done exhaustive research (although both may very well have informed her writing). This reader often felt like a wet-behind-the-ears newbie who is being shown the ropes by some put-upon grizzled veteran who has long-survived the wars of office politics and has the bad posture, jaded outlook, and paper cuts to prove it. Lévesque’s sharp observations and intimate style capture the intangible atmosphere of any office work space: that peculiar mélange of oppressive tedium, womb-like security, and Kafkaesque hypervigilance concentrated between the baffles of a fluorescent-lit cubicle.

“Lévesque introduces a refreshingly random sense of mortality to offset the stale bureaucratic air.”

When delving into the lives of our three Lost Annuitants, Lévesque introduces a refreshingly random sense of mortality to offset the stale bureaucratic air. After many years away from Taiwan, Lee Gaik Wah returns for a visit with her poet friend Janet (who had lived there herself once and has a nostalgia for the place that seems imperialistic and foreign to Gaik Wah). While visiting the temples, they experience a minor earthquake that creates a momentary panic.

“Gaik Wah felt woozy after the tremble and, for the rest of the day, slightly nauseated. As if her bearings had been shaken loose, her balance centre disrupted during the few seconds that the earth shook beneath her. She had put a pinch of oolong in a mug and gone down the hallway to get hot water from the dispenser. There was one on every floor in most hotels. This one was located in a utility room. She stood at the window while the tea steeped and cooled some. She was on the nominal fifth floor but in reality it was the fourth; in Mandarin ‘four’ and ‘death’ are homonyms, making the numeral unlucky.”

Caroline Melançon constantly assesses and reassesses her identity as a mother and wife, until one morning it is all unexpectedly and starkly put in perspective.

“She dropped two slices of bread in the toaster and crossed the kitchen to open the vertical blinds at the patio door. A bear was her first thought. Even though she hadn’t seen one since leaving Goldfield forty years ago. But it was a man. He was hanging by the neck from the oak tree.”

Stephen Higdon, like many a young person, goes travelling to India, hoping to find himself, only to encounter further confusion. Ironically, far from the conventions of public service, his experience correlates with how many of us feel about bureaucracy.

“Higdon still hadn’t figured out the significance of wearing white. Early on someone had told him that it was for mourning, but he doubted it. He didn’t understand a thing about this country. Half the time he didn’t know what was going on around him, what people were doing or why. What he took to be a religious gathering – an exuberant procession in the night, complete with painted elephants – would turn out to be a political rally. What he assumed to be a protest was a funeral. It was one fucked-up place.”

Sprinkled throughout the book are many references to the Coen Brothers’ film The Big Lebowski. Although I’ve seen some YouTube clips, I’ve never watched the movie in its entirety, so I can’t fully say what relevance it has to the novel or its characters, except that they seem to love it. But I can add my own pop culture reference that, I believe, shines some light on the power of Lévesque’s narrative.

Anyone familiar with the TV series Severance, where employees at an ominous corporation have undergone a medical procedure that splits their work identity from their civilian identity into two entities: innie and outie (the belly-button imagery being a witty side comment on their predicament), will find The Secret Life of Public Servants to be a barbaric yawp that would make Walt Whitman proud. It gleefully erases all the boundaries we normally associate with work life and private life. It rails against everything that would divide our many selves from each other in the human struggle for identity and meaning.

Lévesque has crafted an original and imaginative meditation on all that is extraordinary in our ordinary lives. I highly recommend it to any serious reader of contemporary fiction.

About the Author

Born in Rimouski Québec, Anne Lévesque grew up in a working-class home in a small town north of Lake Superior. She holds degrees from Laurentian University and Acadia. Her poetry, short fiction and essays have appeared in literary journals and anthologies. Lévesque is the author of two novels; 'Lucy Cloud’ and ‘The Secret Lives of Public Servants’. She lives on the west coast of Unama’ki Cape Breton Island.

About the Reviewer

Steven Mayoff is a novelist, poet, and lyricist living on PEI. His website is www.stevenmayoff.ca

Book Details

Publisher : Galleon Books

Publication date : June 20 2025

Language : English

Print length : 256 pages

ISBN-10 : 1998122166

ISBN-13 : 978-1998122165