The Song of the World: Short Fiction by M. G. Turner

Exclusive to The Seaboard Review of Books

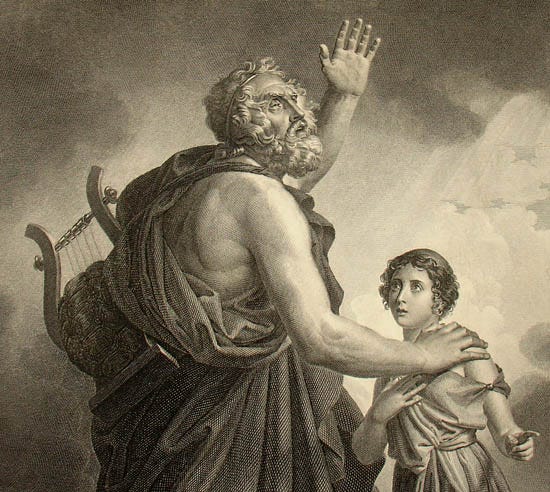

No one knew from whence the blind bard hailed. It was like he simply appeared, gnarled staff in hand, confidently climbing those rocky Anatolian hills despite his age-old blindness. Some said he had been brought to their shores a slave, by pirates, having entertained them on their long sea voyages; others that he was a true son of Asia Minor and came from a kingly lineage of bards almost as old as the known world; and a few who accused him of witchcraft. Thanks to his skill at storytelling, for the superstitious minded, he had to have witnessed the destruction of Ilium itself, perhaps before darkness had stolen his vision.

But whatever his origin, at night, when the whole village was craving something other than cooked food or the warmth that came from their makeshift braziers, they would beseech the wandering fellow for a song, seeing as he was the most well-traveled bard they’d ever known. And so, while the entrails spat on the grill and the populace took their weary rest the bard would sing to them without a quaver in his voice or a false note in his song. So well-practiced was he, he could give voice to every voiceless ghost and to all the venerated dead, those whom his lofty line were said to have sung about since before the Fall of Troy. Indeed, the men of Ilium were immortalized in his lays, Hector and Priam, Paris and Aeneas; so to were their Greek aggressors, the wrathful Achilles, the envious Agamemnon, and every other name that floated in the air, apt to be snatched up by the mysterious troubadour and painted upon his metaphorical mental canvas. Then sometimes, as the village sat around the fire, the men and women together, and their children beside them, the bard’s song would shift and he’d sing of Odysseus, the most cunning of the Greeks, and his decades long odyssey to reach the shores of his native Ithaca. Indeed, as the waves lapped the Anatolian shore and the staggering smoke of their bonfire kissed the sky, it was as if his images, illustrated by a tongue imbued with mystery, were taking shape in the air: the heroes and the horses, the men and the gods, forming intricate shapes within that dazzling spectacle of flame. For one young girl this stood out to her most vividly, and she could not help waiting eagerly for the burnished sunset and the feast which would always conclude with the old man’s decorous paeans that never failed to bewitch her mind with the loveliest and most heart-rending fancies.

It must be said, if it has not yet been inferred, that their coastal life was difficult. People often died before their time and the necessities of fishing and farming took an immense amount of fortitude. There was confusion about the gods, and about the stars, and fear of their neighbors, and the wars that were forever being waged. They feared the black ships that sometimes anchored by their village and they feared the men who spoke in strange tongues and who bore flashing swords. The men feared for their women were they to lose their lives by sickness or by circumstance, while the women feared for their men were they to die in childbirth and leave their families alone. The Underworld was a perennial concern and coins adorned the eyes of the dead, as they interred them in the earth or burned them on the pyres. The sea and the sky were regions existing on top of each other, and their concurrent gods sometimes made war and sometimes made love. When something went wrong these gods were blamed, and when something went right they were celebrated. But despite all these vicissitudes it was the bard who’d graced their village with his presence who provided the populace with a few moments of respite from the acquired agonies of agrarian poverty, of which they knew no other way, but simply accepted as if were their lot.

But not the girl, who loved the bard’s nightly song and would often sing it to herself in quiet moments as she went about her daily chores. The tales of Troy were always told at sundown and thus she welcomed the night with open arms, though many around—like her brothers—feared it. But the bard did not fear it either, for it was always dark where he was, his glazed eyes having forced him to develop a second sight which peered through the heart, rather than the eye, a sight inspired by the many muses whose influence was delivered by the winds.

And oh, the crises of Ilium! And oh, the Fall of Troy! And oh, the death of Patroclus and the grief of Thetis’ son! And oh, the great wooden horse with all the Greeks inside of it! And oh, the suffering of Odysseus who longed for his patient Penelope, distracted by her loom!

Soon yet one more difficult season came to the village. War had ravaged the lands far afield and this put a desperate feeling into the hearts of the villagers. As if in punishment for mankind’s dastardly deeds the crops did not grow as they had in previous years and the fish were not as plentiful; some went hungry and a cattle blight scoured the pastures. The trees had turned brown and the groves lacked the usual blessings of olives. But still the bard sang on, through his hunger and through their plight; still he told stories of Achilles and Ajax, of Telemachus and of Nestor. And still the girl, older now, listened, and in quiet moments beseeched the bard for answers about their predicament, and he would only smile and say that it was the will of the gods, and the only thing to do was to sing what he called “The Song of the World,” a song, which had been passed to him by his forefathers and which he hoped one day to pass down to the next deserving soul, for those high bardic qualities lived not only in the blood, but in the spirit, and he saw that the girl had this spirit too, and often sang to her with this magnanimous intention in mind.

Yet one day, despite the improvements in their lot, for they had finally had a bountiful season and the drought had seemingly passed with the winds, the bard, ever so steadfast in the face of Demeter’s neglect, fell sickly and ill. Thus he laid out in the shade of a tree, and hummed to himself what the girl took to be a calming melody, but which he did not seek to share with her, for it was his death poem, and a private offering to his personal muse. Still, she asked him what was wrong, and if there was anything she could do for him; all he asked for was cheese and a little milk, which they now fortunately had ample stores of. She brought him these items, as well as some bread and olives and they sat together under the tree, looking out at the vast blue ocean, though to him it was a “wine-dark sea.” He had never sung his song in the daylight, but now he took her hand and sought to grant her some indelible part of himself which could no longer house itself within his shrunken frame, passing it to her on the breath. Thus by whisper he freely shared with her the secrets of his linage, and when he was through she found herself changed. Suddenly she knew it all, every story and every stanza, and could trace each character as though they were a separate point of light in an ever-growing constellation, being mapped by all the disparate bards who’d deigned to add a pinprick to this exquisite and deathless weaving.

Besides this moment of immaterial mysticism, the practical fact was that she had heard his song a thousand times, on a thousand days, and in a thousand ways; it existed very much inside of her and knew with a little practice and a little honing she could sing it too. The bard had known this well, and that was why he’d chosen her, and why as the evening began to fall and the stars emerged and the village encamped about the braziers, he attempted to sing once more “The Song of the World.” But he was too weak in body to make it through, and so for the first time, she joined him, raising her voice to speak when his had faltered, and reminding him of where he was when his memory lapsed. The villagers celebrated whenever she stood in for him, whenever she took his hand and with a quiet word strove to settle his breathing which was growing increasingly labored.

Sadly, he did not make it through the night. He expired with a sigh just as Odysseus reached Ithaca, but before he reclaimed his awaiting throne. But it was no matter, tomorrow she would pick up the tale where he’d left off, and each night hence she would be the bard, and as the years passed she would find her own small protege, and they would pass on this story so that humankind would never forget what happened to the Trojans, to the Greeks, and to the Gods. But it would not be her time for many years, and there were many stories to be told and questions to be asked, and pathos to find amid the scattered verses which had fled from her mentor’s mouth and found expression in the air.

And so they burned the bard, who was then called Homer, upon a pyre, as the spirit of the poet-sovereign fled up to the stars, while his song stayed down below.

About the Author

M. G. Turner is an author and literary agent in New York City. His first full-length book, “City of Dark Dreams: Tales from Another New York,” will be published by DarkWinter Press in January 2027. In 2025, he published his first book, “Dreams of the Romantics,” a chapbook story cycle about the English Romantic poets and their gothic lives which was reviewed favourably by The Seaboard Review of Books and by renowned critic of weird fiction S. T. Joshi in his periodical Spectral Realms; it is being sold in bookstores in NYC. His other books are a story cycle about Ancient Rome, “Roman Visions,” a poetry art book, “Sotapanna," "Reader Faustus: A Novella in Verse" and the just released "The Museum of Mind and Matter.” In 2025 his personal essay on movie special effects pioneer Ray Harryhausen was published in the Winter issue of Videoscope Magazine. He also has a gothic tale called “The Apparatus” in the new horror collection “The Promethean Archives,” from the indie press The Words Faire. In 2019, Turner was the editor of the KGB Bar literary journal and ran events and open mic nights at the storied literary venue. In the literary field, he has worked with numerous distinguished authors and scholars including photojournalist Ruth Gruber, Eloise illustrator Hilary Knight, and “Boys in the Band” playwright Mart Crowley. As a student he won a Scholastic Award for fiction in the category of humor. He may be reached at mgturnerwriter@gmail.com.