TSR Hot Takes: Brief Notes on Books Present & Past

An ongoing collection of our contributor's Hot Takes from our weekly issues

(Note: clicking on the underlined link takes you to the book’s publisher page for more information or for purchasing purposes)

The Plains by Federico Falco (Charco Press, 2024) The Plains by Argentinian writer Federico Falco chronicles the aftermath of a life-changing decision the narrator has made to leave Buenos Aires following the breakdown of his relationship with his lover and partner, Ciro. The narrator is a writer and teacher of creative writing, a city dweller his entire adult life, so the decision to leave the city for rural Zapiola, in the Argentinian Pampas—farming country—is something of a paradox. The story the narrator tells is of the land, the seasons, the weather, interspersed with personal anecdotes about family, encounters with neighbours, the relationship just ended. The Plains is a contemplative novel, one that sets a rhythm that the reader either settles into or resists. Falco’s prose is filled with lush sensual descriptions, some pleasing, others not so much. The story builds slowly, its emotional impact for the most part muted. In the end, we may not share the narrator’s enthusiasm for the country life he's chosen, but we can see and perhaps understand the allure of new and unfamiliar possibilities in the wake of a devastating emotional crisis. (Contributed by Ian Colford)

Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval (2024, Verso) In Paradise Rot, Jo, a young Norwegian woman, has arrived in the English town of Aybourne to attend college and study biology. She has no place to live and initially stays in a hostel before securing a room in an apartment located in a converted brewery. Her roommate in the brewery apartment is Carral, who works as an office temp and has a degree in English Literature, but reads trashy romance novels. From the outset, Jo’s narration emphasizes her physical surroundings, the fleshly textures of the food she eats and the people around her: “The food in the breakfast hall was slippery and fluid.” And, “The foreign students too were smooth and gleaming.” This is a novel that spins an elusive flesh and blood tale of bodies stewing in their own juices. It’s as if we’re observing specimens under a microscope, cells clinging to one another, consuming each other. The world of Jenny Hval’s first novel is familiar but alien and hints at something unsavory just below the surface, but well out of sight. Paradise Rot does not divulge its secrets. But it does leave an imprint on the reader that is not quick to fade. (Contributed by Ian Colford)

Vigil: Stories by Susie Taylor (2024, Breakwater Books) Each story in Vigil places you in the fictional town of Bay Mal Verde, a town struggling with addiction, violence, and poverty. The characters in this town are doing what they feel they have to do to get by, whether that's dealing drugs to make some money or taking pills to fill the emptiness. Some of the characters stand out as leaders in the community, while others blindly follow wherever they are led. Some have already given up, while others are still holding on to hope. They want what everyone wants: to love and to belong. I loved every story, right down to the unexpected “Resurrection” of Stevie Loder, five years after his death. (Contributed by Naomi MacKinnon)

Our Wives Under the Sea by Julia Armfield (2022, Flatiron Books) Marine biologist, Leah, becomes stuck for months in a research submarine, and returns home changed. Her wife, Mari struggles to cope with Leah's transformation after her return, and cannot get any answers from Leah's employer about what happened on the submarine. This dual-timeline novel is beautifully written and will leave you wondering about the line between perception and reality. Thoroughly enjoyed the read! (Contributed by Pamela Sinclair

Betsy Warland's Bloodroot: Tracing the Untelling of Motherloss (2021, Inanna) is a meditation on grief that refuses the tidy resolution so often expected of memoir. This second edition, published by Inanna Publications, reaffirms Warland's reputation as a writer unafraid to push the boundaries of form, layering personal history with poetic fragmentation to mirror the uneven terrain of loss. Warland's mother, an enigmatic and often distant figure, becomes both presence and absence, haunting the text through memory and the gaps between what can and cannot be said. With the precision of a poet and the insight of a seasoned essayist, Warland transforms personal mourning into a deeply intellectual exploration of language, silence, and the ways in which we attempt to narrate the unutterable. Bloodroot is not merely a recounting of loss, but an excavation of its residual weight, reminding us that some absences shape us as profoundly as presences ever could.” (Contributed by Selena Mercuri)

The Queen (2025, Simon & Schuster) by Canadian creep-meister Nick Cutter is a deeply visceral read for fans of detailed gore and unfurling mystery both. With shades of the Alien, and the yuck of various bugs and the psycho-fuel of teenage pheromones amped up by something diabolical brewing out of sight, The Queen draws readers into an anarchy of arthropod fury. Cutter uses the cat nip device of treasure-hunt clues left via iPhone by someone who's got it out for plucky teen heroine Margaret Carpenter, who combines the wiles of Riley from Aliens and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. (Contributed by Emily Weedon

Death in a White Tie by Ngaio Marsh (1999, HarperCollins Canada)“While the 'hot take' is that the world is regressing into the 1930s, I picked up some 1930s reading. Ngaio Marsh has been called one of the Queens of Crime - alongside Agatha Christie - writing what now would be called cozy mysteries. Marsh's settings are delightfully retro, while her main characters are surprisingly modern; Detective Roderick Alleyn calls his wife, by her last name, and independent “Troy” has kept her career as a celebrated painter, while helping her husband solve murders. Steeped in an era, infused with glamour, and wittily written, Marsh is a delightful find for an escape from the current tensions in the world.” (Contributed by Heather McBriarty

Berth by Carol Bruneau (2005, Nimbus Publishing) Willa Jackson, the lonely wife of a helicopter technician for the Canadian Air Force, falls for the attention of Hugh, an attractive saxophone player (and lighthouse keeper). When her husband Charlie is on a tour of duty, Willa leaves her present life and moves, along with her nine-year-old son Alex, to Thrumcap Island in Halifax Harbour. The Island, however, harbours secrets, some from the former keepers, some from when the military used the island for military practice, and some from Hugh’s past. Carol Bruneau’s writing has always fascinated me, and this novel from her back catalogue is no exception. She builds tension and suspense in her unique way. Well worth finding a copy, you won’t be disappointed. (Contributed by James M. Fisher)

Catherine Bush’s novel, Blaze Island (2020, Goose Lane Editions) bases itself on Shakespeare’s The Tempest to comment on climate change in Newfoundland. Bush’s lyrical prose captures the island’s language and landscape beautifully, and the reader is drawn into the lives of her main characters as well. The main drawback, however, occurs in the didactic melodrama of a rushed ending with its cops-and-robbers chase gathering alongside its moral lesson of climate disaster. Her major characters are finely developed, but her minor characters are less appealing. She briefly introduces the protagonist’s grandparents, who mysteriously never appear to look for their lost granddaughter stranded in Newfoundland. (Contributed by Michael Greenstein

The Forgotten by Robert W. Mackay (2025, NON Publishing) is, as its subheading says, “A Novel of the Korean War”. I have read novels based on other wars, but this was the first set in the years of the Korean War (1950-1953). It follows Charlie Black and the 13th Platoon as they find themselves no longer peacekeepers, but a fighting unit in an all-out war. Author Robert W. Mackay, himself a Canadian Navy vet, has penned a page-turner of a war novel that has embodies all the fears of the young men sent to fight there.

“The ear-splitting crash of twenty-five-pounder shells reached a crescendo and stayed there, explosion on explosion fractions of a second apart. The ground shook. a The sheer terror of lying in a hole in the ground while ran- JI dom forces beyond his control decided whether he would live Or die constituted an unspeakable horror of its own.”

From their training to their overseas voyage by ship to their on-the-ground fighting, tasked with taking hill after hill back from the Chinese and North Korean troops, we are with Charlie and 13 Platoon as they experience the horrors of war. Recommended for those who enjoy a well-written war novel. (Contributed by James M. Fisher)

“I co-read the work with my resident young adult and we agreed: the author is very, very excited about science, knows a lot of stuff, and could really use some editing, shaping, and focus: the metaphors come fast, loose and mixed and the sentences can be run on — suggesting a brainy writer who has more excitement for ideas than discipline to craft prose… yet. An attempt to connect the dots is more of a scattering of dots, as strewn as the stars themselves

The Language of the Stars ((2025, Linda Leith Publishing) by Nathan Hellner-Mestelman attempts to mash overwrought teen-angsty verbiage with a mind bending slurry of factoids about the universe in a slim, almost harried volume. I was, in these earthbound, politically fractious times looking for hope in the unifying elements of the cosmos, peace in the silent reaches of space and time, which is why I picked up The Language of the Stars. There's something soothing about the idea of. exploding stars when compared to the times we live in!

I co-read the work with my resident young adult and we agreed: the author is very, very excited about science, knows a lot of stuff, and could really use some editing, shaping and focus: the metaphors come fast, loose and mixed and the sentences can be run on - suggesting a brainy writer who has more excitement for ideas than discipline to craft prose... yet. An attempt to connect the dots is more of a scattering of dots, as strewn as the stars themselves. The Language of the Stars tries to be all that for a young adult audience and update the vibe of a Brief History of Time. The author is very young, at only 17 themselves, so their molten magma proud nerd-core fuelled prose has plenty of time to cool and coalesce, doubtless into mature star-worthy works in the future. (Contributed by Emily Weedon)

River Faces North (Taggak Journey Book 1, FriesenPress 2024)) A most powerful read. Anti-utopia may appear grim, but the skill of Anne Smith Nochasak turns the reader's journey into a quest for timeless values: standing one's ground, protecting one's own, never betraying one's beliefs, following one's moral compass. The understated humour that suffused the author's writing in her previous novels, is the canoe in which she navigates the troubled waters of the narrative. Her subtle writing pulls one inside the story, so much so that you are experiencing every moment, every thought the protagonist Flo experiences. And you become invested in the future of all the other characters, none of which is minor. A rare achievement. So looking forward to the sequel!

(Contributed by Maria Haka Flokos. M.K. Haka was born in Greece and read Architecture at Cambridge (Girton 1980). An avowed Anglophile, she returned to Greece to practice architecture and currently resides in Athens with her family. The Hesitant Architect was her first novel. The Eyes of the Rock Partridge is her second one, currently in working progress, as is the direct sequel to the Hesitant Architect, Their Brilliant Innocence. https://www.alumni.cam.ac.uk/benefits/book-shelf/the-hesitant-architect

Absurdities abound in Survivors of the Hive, (2023, Radiant Press) a collection of four unbridled fictions by Kingston author Jason Heroux (The Amusement Park of Constant Sorrow, etc.). These are surreal tales of people adrift in a world without boundaries, where meaning is fluid, where the past bleeds into the present, where veracity has skipped a beat and no longer seems tethered to a reality we can recognize. Heroux’s fictions constantly surprise and occasionally confound. Again and again, he propels his narratives down a rabbit hole of non-sequiturs where we encounter hellish environments and unsolvable conundrums. Logic plays little role in the actions of Heroux’s characters. On page after page, we witness people behaving against their own best interests, glibly making life-altering decisions on the flimsiest of pretexts. Survivors of the Hive gleefully thumbs its nose at narrative convention and will likely not appeal to readers who like their fiction to follow a straight and narrow line. Unapologetically over the top, its excesses are deliberate and its storylines thoroughly loony. But it’s also fearless, endlessly inventive, and a helluva lot of fun. (Contributed by Ian Colford)

“I recently read two chapbooks published by Agatha Press that I picked up on a trip to Edmonton in December of last year—Ground Cherries by Danielle Paradis and Bloody Women by Bree Taylor. Poetry Month is a perfect time to check out some short poetry reads. In Ground Cherries, Danielle Paradis cultivates beacons of kindness for a childhood past and life in the present. Challenging memories are delicately intertwined with the possibilities of seeds planted. Each poem in Bree Taylor’s Bloody Women is after a character that embodies the chaotic, skilful, horrific, powerful, intellectual, messy, and mean. Amidst all the ways women are despised, these poems throw it right back on the systems and sentiments set on making villains of us all.” Link to Agatha Press:

https://www.agathapress.com/

(Contributed by Samantha Jones)

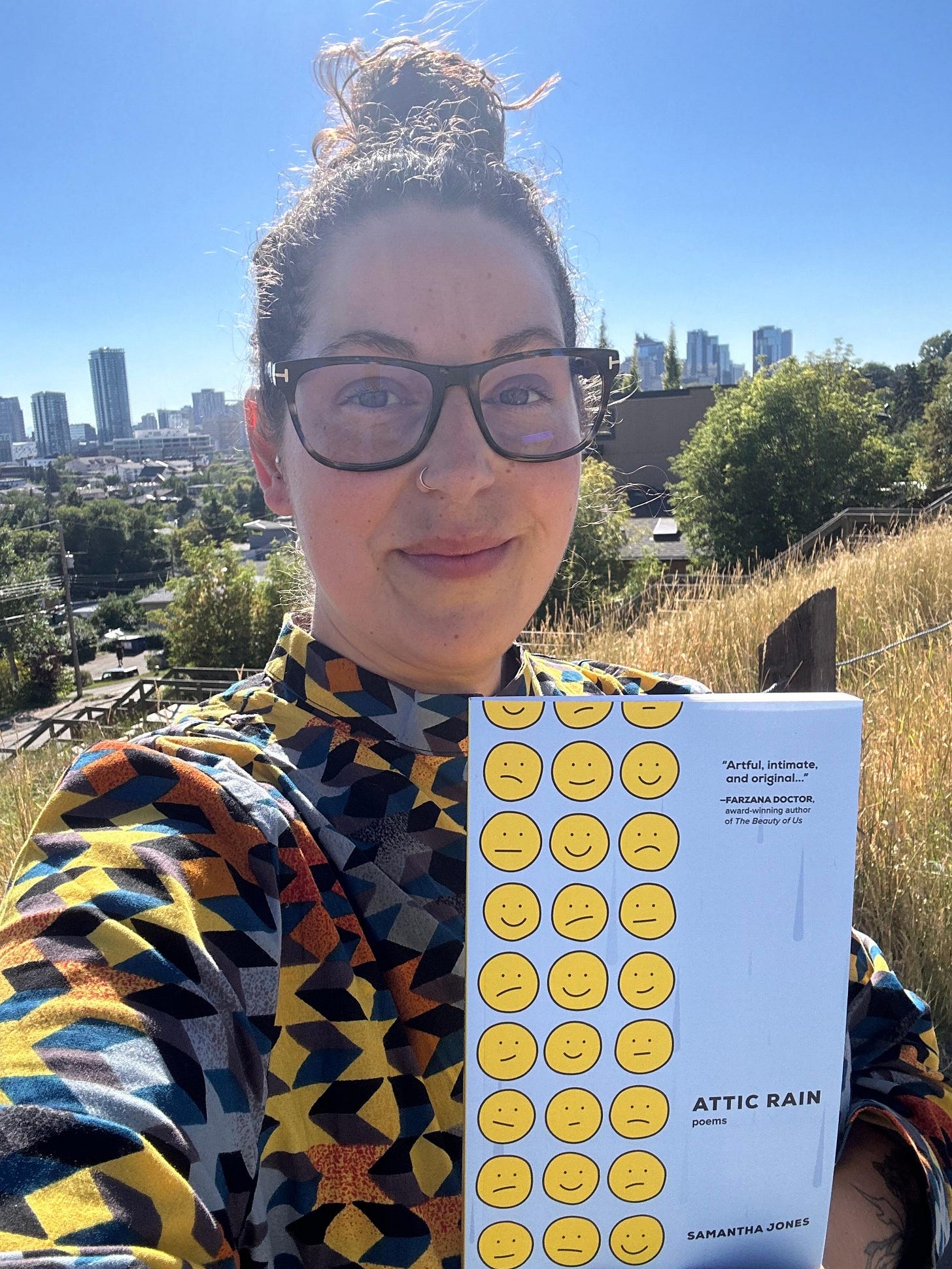

TSR welcomes Samantha Jones as a contributor! Samantha is a poet, editor, and earth scientist based in Moh’kins’tsis (Calgary, Alberta). She is Black Canadian and white settler with roots in Nova Scotia, Québec, and Ontario. Her poetry collection, Attic Rain, is available from NeWest Press.

In Great Silent Ballad, A.F. Moritz continues his longstanding exploration of lyric poetry as a vessel for moral clarity and historical memory, offering readers a collection that is both hauntingly intimate and profoundly civic. Across its meditative structure, the book foregrounds poetry’s potential not as escapism, but as a means of bearing witness to the slow violences of the modern world—capitalism’s degradations, ecological collapse, and the enduring wounds of historical injustice. What emerges is a version of lyric attention as an act of resistance: a way of preserving the dignity of human experience in a time increasingly hostile to reflection. The collection’s primary strength lies in its subtle juxtapositions—private grief set beside public horrors, mythical elements tangled with contemporary allusions—all rendered in language that is precise and musical. Engaging in tacit dialogue with poetic forebears like Jiménez and Blake, Moritz situates the Canadian lyric tradition within a broader, transhistorical conversation about beauty, innocence, and aging. Great Silent Ballad is a masterful continuation of Moritz’s oeuvre, as well as a reminder that the lyric, at its best, still holds the power to transform attention into ethical insight. (Contributed by Selena Mercuri)

Universal Health Care

Danielle Martin, Better Now: Six Big Ideas to Improve Health Care for All Canadians (Penguin Random House Canada, 2018)

Jane Philpott, Health for All: A Doctor’s Prescription for a Healthier Canada (Penguin Random House Canada, 2024)

Few would disagree with the assertion that Canada’s health care system is in trouble. Seventeen percent of adults have no regular access to a health care provider.1 Patients languish on waitlists for specialist access2 and surgeries.3 People are forced to choose between food and filling their prescriptions.4

Some narratives maintain that privatized medicine is the answer. Not only would this option worsen health care access for the large swathe of the population who can’t afford private care, but it distracts us from better solutions.

In their respective books, doctors Danielle Martin and Jane Philpott (former federal Minister of Health) present concrete alternatives for restructuring Canadian health care so that it is affordable and serves everyone. In addition to emphasizing access to primary care, they both advocate for addressing health care “upstream,” by considering social determinants of health such as adequate income and housing. Investments in these areas would not only realize human rights to these basics but, by maintaining health, would lead to savings by lowering demand for medical services “downstream.”

Both books provide not only hope but a plan. With the political will, health care for all is possible. (Contributed by Janet Pollock, a writer and educator living on lək̓ʷəŋən territory in Victoria, British Columbia. Under the pen name Janet Pollock Millar, she writes fiction, poetry, essays, creative non-fiction, and book reviews. Her work has appeared in publications including Herizons, Prairie Fire, The Fiddlehead, Pangyrus, and The Malahat Review. Janet works in the Writing Centre at Camosun College.

Sources:

“Better Access to Primary Care Key to Improving Health of Canadians,” Canadian Institute for Health Information, accessed March 13, 2025, https://www.cihi.ca/en/taking-the-pulse-measuring-shared-priorities-for-canadian-health-care-2024/better-access-to-primary-care-key-to-improving-health-of-canadians

“Why Do Canadians Wait So Long for Specialist Doctors?” Canadian Medical Association, accessed March 13, 2025, https://www.cma.ca/healthcare-for-real/why-do-canadians-wait-so-long-specialist-doctors

“Wait Times for Priority Procedures in Canada, 2024,” Canadian Institute for Health Information (4 April 2024). https://www.cihi.ca/en/wait-times-for-priority-procedures-in-canada-2024

“Almost 1 Million Canadians Give Up Food, Heat to Afford Prescriptions: Study,”Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, February 13, 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/canadians-give-up-food-heat-to-afford-prescriptions-study-says-1.4533476

K.R. Wilson’s Guernica Prize-winning novel, An Idea About My Dead Uncle, tells the absorbing, unsentimental story of Jason Lavoie, a young man of Chinese origin, raised in Canada as a North American, searching for answers about his ethnic heritage. A mystery of long-standing that has consumed the family concerns his uncle LiHuang—known as Uncle Larry—who left Canada in the mid-1970s for China, sent a few letters home, but for 25 years has been incommunicado. After Jason's relationship with girlfriend Louisa falls apart when she discovers his affair, he travels to China to learn what he can about his uncle’s fate. K.R. Wilson writes sharp, uncluttered prose that carries the reader along on waves of dramatic urgency. The scenes set in China are especially effective because of the earnest yet haphazard nature of Jason’s quest and the obstacles fate seems to place in his way. The novel ends in a surreal, shape-shifting dreamscape as Jason’s resolve abandons him and his psyche shatters under the pressures he has placed on himself. An Idea About My Dead Uncle is a poignant debut novel that explores issues of ethnic identity with a clear, unforgiving eye. Even though his actions are not always admirable and sometimes self-destructive, his vulnerability makes Jason Lavoie an appealing narrator, and we set aside our misgivings and stick with him until the end. (Contributed by Ian Colford)

Amal El-Mohtar’s novella The River Has Roots is a retelling of the folktale "Binnorie," which more people may know from Loreena McKennitt's song, "The Bonny Swans." In the folktale, one sister drowns the other at Binnorie mill because she wants her sister's boyfriend. In a classic bit of body horror, the corpse's breastbone is used to make a harp that is strung with the dead girl's hair. When the harp begins to sing on its own, it's taken to the local lord, the dead girl's father, where it outs her sister as her murderer. The River Has Roots departs from "Binnorie" in fascinating ways. This novella has it all. Grammar as music as magic. A sentient river. Two ancient and enchanted willows at the edge of the fairy realm. An asexual and possibly neurodivergent fairy lover. Two sisters whose love for one another defies death. Lush, lyric prose that sings off the page. But to explain more than I already have will spoil this truly lovely story. It is gentle and kind and everything our world-weary souls need right now. (Contributed by Melanie Marttila, Substack: Alchemy Ink)

“and then he was GONE”

This is a 2016 novel by NB author Joan Hall Hovey, about a missing husband who the police are beginning to suspect was murdered, a wife determined to find him despite being the prime suspect, a young man who wakes from his 19 year coma and a psychic aunt who sees the truth. A thriller with a sprinkling of the supernatural, Hovey has penned a deliciously written, nail-biting, and thoroughly satisfying mystery. I rated it 5 stars and immediately picked up a few more from this talented and engaging writer. (Contributed by Heather McBriarty)

When the Moon Hits Your Eye by John Scalzi

It will be no surprise to those familiar with John Scalzi’s writing that premise of his most recent book is a bit out there. When the Moon Hits Your Eye follows on the heels of The Kaiju Preservation Society, which released in 2022 and Starter Villain, which came out in 2023, and is similar to both in the believable unbelievability of the story that unfolds. When the Moon Hits Your Eye depicts what happens after the moon turns to cheese. The book is presented in a day-by-day format, and each chapter explores the impact of the moon’s sudden change on a different person or group of people. Among the characters are astronauts whose planned moon mission is suddenly cancelled, cheese store owners, space museum workers who discover that moon rocks on Earth have also turned to cheese, and ordinary people trying to make sense of it all. Scalzi’s typical wit, and his ability to make the unreal seem real enough within the confines of the story, make this a fun read. Those who enjoyed Scalzi’s last two novels should get a kick out of this one, too. (Contributed by Lisa Timpf)

Blood Slaves by Markus Redmond

Markus Redmond’s concept - well deserved retribution rains down on racists/white slave owners when the enslaved protagonist Willy crosses paths with a new kind of vampire - is audacious and grabby. The debut novelist’s plot concept perhaps owes more to Quentin Tarrantino’s Django Unchained, Kill Bill and Inglourious Basterds than it does Bram Stoker and his spawn in that it sets up scum of the earth bad guys who deserved to be fully reaped for their evil by a dire reckoning force.

There is a passing mention of avoiding sunlight, by Rafazi, last of the Ramanga Tribe in Ghana of the year 1407, and his requisite need for blood, preferably human, to survive as the undead. There are also glowing eyes and a very perplexing bit about a forehead that engorges and extends when the ghoulish creature is supernaturally aroused by blood. I’ve worked with creature creators on a few film sets. I can well imagine the latex and mechanical cervos involved in creating a pneumatic forehead rig…

Pitted between the ancient wiles of Rafazi and the rapacity and casual torture and homicide of the slave owners are Willy and Gertie, sweet, steadfast lovers who hang on to their humanity and inherent decency.

The concept is compelling, and easy to see why it was picked up in this time of cultural reinterpretation. Though the premise is strong, the prose and story have deficits.

The opening, media res action in a battlefield could have been very exciting but is marred by clunky expository dumps. Deep past expositions explaining how we got here would have better served the novel in the deep heart of the story. Characters are thin and cliche across the board. The sneering, menacing tobacco chewing good old boys, trembling, victimized women just trying to keep their head down, booming voiced, physically imposing white landowner who feels entitled to everything. They don't feel like people with personal individual goals. Instead they seem like blank canvases upon which to etch deep suffering or pure evil. Extended scenes of torture and rape and violence which focus closely on what is happening to people does not reveal their character further and risks running into trauma porn.

During a rape scene, women are handled like mere puppets or props, objects of male gaze three times over: their victimizers, the watching protagonist and us with the net experience of feeling exploitive. The lack of plot and character development combined with highly charged emotional scenes reduces what could be powerful to melodrama. There is a lot of social commentary out there these days, so even melodrama comes as a slight relief, but I feel this book could have been more, gone deeper, been more refined with steady editorial. Those who insist on trigger warnings will want them, as there is much to be triggered by. Though I am loathe to suggest trigger warnings for a horror. I think the violence and mayhem suggested by the genre, title and the book cover together should theoretically be considered fair warning.

Redmond writes using African American Vernacular English, telling much of the story from inside the language of the main characters, in the parlance of their time and place. However, deployment of dialog runs generally into the declarative, into character tropes, lacking nuance or personality. The antagonists especially give into frequent monologuing, telescoping their every action, undercutting what could be even more brutal violence by allowing the acts to exist, blunt, harsh and horrific. When rummaging around in horror, wrestling with evil, less dialog is often more, just as seeing the monster too much breaks the delicious spell of other worlds.

All of this may be intentional. The breezy highflown description and on the nose dialog from tropey characters put together with the painted claw hand crushing a plantation in its grip on the cover adds up to a romp-y B movie vibe. Tarrantino waded in the waters of B movie while adding heft to the pantheon of American cinema. Schadenfreude may well be best served with a side of cheese. It is possible that I am not the exact market this book is aimed at, and that a horde of Jane Austen Zombie fans will devour this.

I am of the belief that the vampire myth persists with the tenacity it does because of the potent mix of sex and death - inevitabilities for life. The meat of Blood Slave is revenge and rebalancing power. I frequently wondered while reading it if a better supernatural beast to tear the overseers apart might not be zombies which always conjure the idea of swarming, unstoppable, mute disease, or werewolves which channel rage atavistically into beasts, suggesting we as humans are never far from our animalistic roots, or a shapeshifter like Carpenter’s Thing. I think we can all relate to the idea of longing for a huge, punishing force, or being able to appeal to the avenging God of the Old Testament to right wrongs by taking eyes for eyes and teeth for teeth.