We’re Somewhere Else Now: Poems 2016-2024 by Robyn Sarah

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Back-to-Back

Robyn Sarah’s title, We’re Somewhere Else Now, tells us that place, time, and meaning shift in her latest collection of poetry from 2016-2024, a decade’s distillation before and after Covid. Like her unassuming title, the first poem, “Chandelier,” begins with an understated couplet: “I woke up one day and the world was out there, roaring and / being the world, almost as though nothing had happened.” Meaning unfolds through Sarah’s repetitions: “world” appears in both lines with shades of connotation from the loud roaring until the poem’s final lines where trees fall “silently all over the world.” Not for nothing is the first part of the book labelled “Once More,” for repetition guides the reader through the poet’s world and patterns.

“Robyn Sarah’s title, We’re Somewhere Else Now, tells us that place, time, and meaning shift in her latest collection of poetry from 2016-2024, a decade’s distillation before and after Covid.”

In this fallen world a chandelier hangs over our head, but not before the second stanza adjusts and positions her focus: “The rest of the interrupted sentence was not gone; it had / somehow jumped to the bottom of the screen.” An unseen pandemic develops through the next stanza in vertical configuration: “Evidence was mounting that we had been hoodwinked, that we were smoke-and-mirrored.” A universal illusion chandeliers the world even though the room is exactly the same, and the next stanza enlarges the unseen virus and modulates its sounds: “An enormous ‘Why’ had begun to form in the sky, and hundreds of smaller why’s suddenly materialized, hanging from the tips of bare branches, disguised as raindrops.” Long i’s sound the mystery and agony of this altered world where question marks and drops merge in the next stanza’s hanging repetition: “It was a kind of chandelier that hung there above our heads – not so very far above our heads. But no one was looking up.” This halo or corona virus is also a guillotine that fells forests and the elsewhere of meaning and breathing space during lockdown. Sarah’s verse is an antidote to the soul’s virus.

Wallace Stevens and William Shakespeare epigraph this book. From Stevens’s “Dry Loaf” we find Sarah’s sense of tragedy: “It is equal to living in a tragic land / To live in a tragic time.” Tragic time informs many of the poems that portray the pandemic in this collection, and Stevens’s presence is strongest in “In the Wilderness: A Soliloquy, in broken time.” Shakespeare’s “Sonnet XVIII” words its way into Sarah’s bare branches: “Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May.” Her chandelier hangs over and illuminates other elegiac poems with her wise voice that probes the “why” of existence and the penultimate “y” of the alphabet.

“Late Journal Entry on a Leap Year’s Phantom Day” questions the calendar’s why: “And how many times can we say / and how many ways can we say / this life’s ephemeral?” She traces the ephemeral numeral in its afterglow of a fading February to conclude: “Not for another four / years will there come / again one of its number.” Her diction seems so direct, but between the words and lines she meditates in musical nuance and wit to cast doubt on simple and complex truths. Thus, the twelve miniatures in “Finders Keepers Losers Weepers” play seriously with found poems and the necessity of keeping them by fixing them in compact units of rhythm and intonation. “The Lost and Found.” That finality at the beginning gets filled in with precise beats in the remaining lines:

Amazing grace, to be reunited with the sentimental scarf, pulled like a magician’s rabbit out of the snarl and hotchpotch of a mildewed wooden crate fished from beneath the counter.

Jaunty enjambment snarls the sounds of sentimental scarf and counter crate – counted in tetrameter and trimeter of wonder, joy, and nostalgia.

Wit and woe mingle in many of these poems. When the poet loses a diamond from her grandmother’s ring while buying a potted narcissus for a present, she concludes: “What an expensive flower!” This final exclamation undercuts any narcissistic impulse. These delightful keepsakes accumulate and resonate:

The rag-bag’s full. All these bright bits kept for a rainy day – but now the sewing machine is frozen stiff with rust, the eye that threads the needle can’t find the needle’s eye.

Wordsworth’s inward eye turns outward in wit’s final reversal.

Sarah’s keepers continue: “We keep a loved animal, / one day to weep its passing.” The penultimate poem of the series spells out its own safekeep:

There are words we keep. Words on paper: clippings, quotations, letters. Words in our heads, words that we ‘have by heart’: poems, proverbs, prayers. There are words that keep us. Do we keep our word?

Honest twists of chiasmus, deft alliterations, and wise wit are memorable and melodic.

After that climactic stanza, the final miniature is anti-climactic in this domestic fugue of miniatures:

For a few moments the cushion still keeps the warmth of the cat that slept there all morning.

Cat and cushion conclude the earlier “Lost Cat” and the rag-bag’s collage of witty familiarity. Sarah keeps her word on the line in playful counterpoint to the lost and found.

She keeps to tradition in her prose poem, “Lit Room,” which draws on a Talmudic distinction between children and building that sound similar in Hebrew. With her combination of whimsey and gravitas, she begins: “In a morning kitchen, a child begins his day.” The poet builds her paragraph gradually with photographic details, illuminating rooms with delight: “Tilting his head from side to side and bouncing a little on his heels – he’s singing.” Sarah’s sentences sing alphabet sounds of lit, tilting, little, and lifted from frame to frame of an opposite window. In their domestic dance across a narrow courtyard the parents kiss and scoop up the child to the window. In the second paragraph or stanza the camera shifts outdoors to expand the room’s horizon. Above the third-floor window, along the roof’s edge, starlings huddle in a row – an avian family to match the human drama just below. “Winter bird-breath comes in little puffs of lit-up steam.” A chorus of short i’s constrict the courtyard with “little” counterpointing the earlier “bouncing a little,” and “lit-up” fuguing literature’s lit room. Small icicles return to the small boy, while from the chimney, “smoke flies in ribbons” against the birds’ steam.

The third paragraph returns to the little boy with his erratic movements: “Zig-zag. Zig and zag. (What governs the zigs and zags? Who can ever know?)” The weave of verse governs childhood lilt, a contrapuntal tilt of words busy being words. Stirring a pot, the mother prepares breakfast: “You know it’s nothing special, it is just breakfast. An everyday feast.” Sarah’s stirring words tilt the Talmud and mundane meal at an angle of striving for the domestic sublime: “What architecture! Their building soars heavenwards” – beyond the stationary starlings and kitchen’s potpourri. Since the book is dedicated to Sarah’s generation, children are a reminder of being somewhere else now.

Her birding continues in “Le Rappel des Oiseaux”: “Call the birds back” forms an insistent refrain in the poem, but also points to Sarah’s “back” directions in other poems. The bird call is a summons and a sound: “The one of the bent wings, call him back, / and the dark one that fell without a sound, / and the white one that rose from the water.” In a flock of sounds she traces flight patterns with lines spiralling downwards: “Call back the coloured ones that sang in the wine, / Call back the coloured ones that glittered in the dream. / Call the birds back, one by one. / Call them by their secret names.” Instead of naming individual species, she groups them by their secret names. (In this French poem we are reminded that “sang” may refer to blood.) These apocalyptic birds are wounded as they descend into a chasm, victims of environmental destruction. Her elegiac call is a rueful appeal to glories of the past – a re-call and remembering.

Similarly, “Tapestry” tracks “ghost birds”: “It’s my mind trying to bring the birds back.” She embraces their sounds, “a counterpoint so familiar,” a fugue of flight through a pandemic where “back” tries to return to somewhere else: “Did I ever really hear them, before memory gave them back?” The final word of the poem is a kind of recitative pointing us backwards to another time, repeated in the once more of a spectral, hypnotic dream sequence.

A bird dance appears in “Do-Si-Do,” patterned from bird to word, back-to- back:

Four sparrows jockey for a perch on a four-perch hanging feeder, then flutter and jostle, each to unseat another for a better.

This poem playfully exchanges sounds and lines of a “four-flit criss-cross / on a two-step ladder” – a chiasmus of choreography, a hopscotch and skip of wit across the page:

switching rungs again and then again

“Part One” ends with a trace of three birds flitting across the bottom of the page, bird-tracks in fresh-fallen snow, black marks reversed on white background, footnotes and flight notes of an artist’s statement.

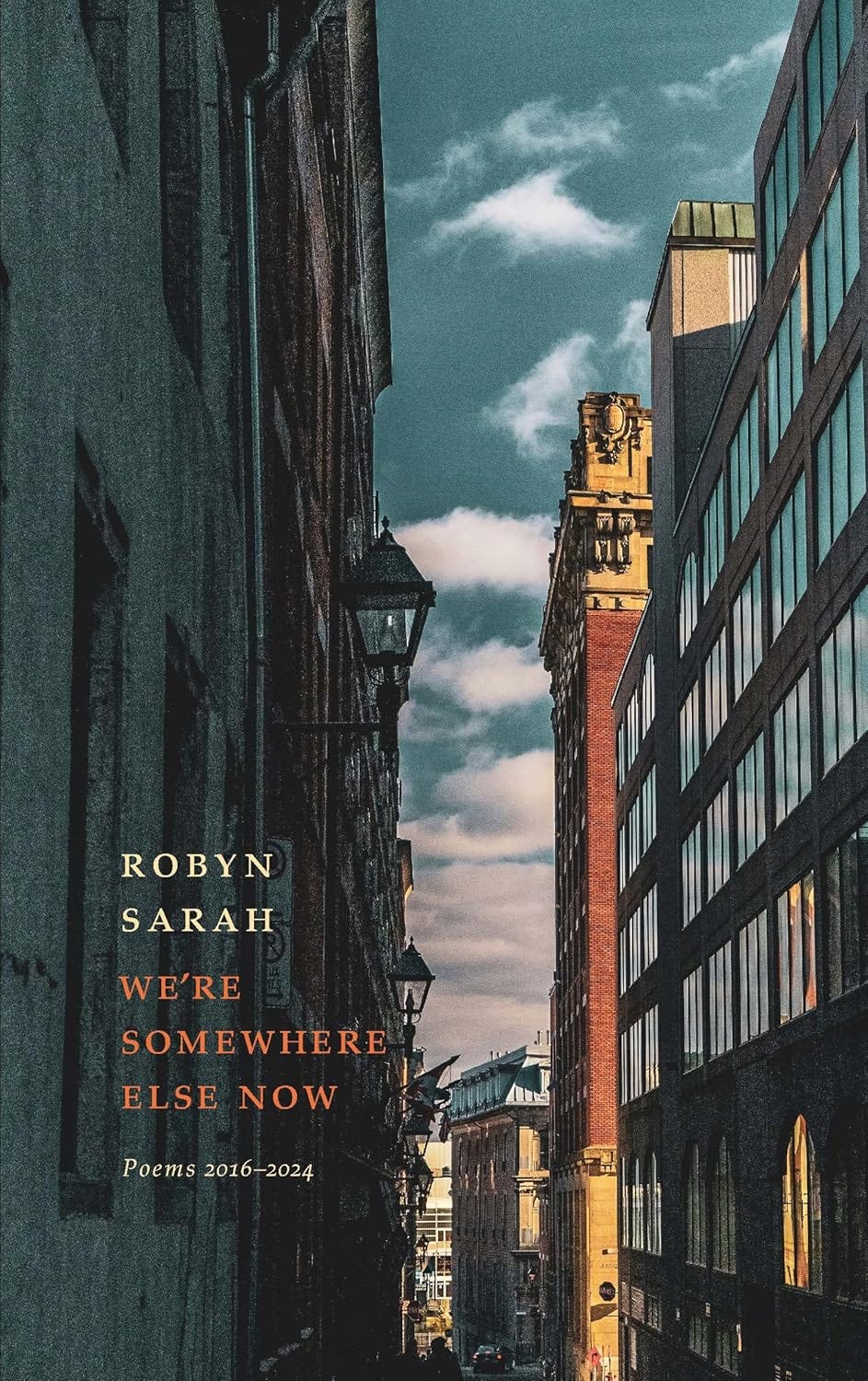

“Flashback (March 21, 2020)” recalls “Virus Time” when the poet visits her pharmacy where a “woman employee in the pharmacy took us to the back of the store” to find one last bottle. She then returns “back home” to her balcony, a perch of observation between buildings. “Nothing’s Happening Here” places her balcony again as observation post that reflects the cover of the book:

Layers of cloud are sailing past the high-rise seen from the lane-side window – balconies stacked skyward like open bureau drawers spilling out glimpses of messy lives.

“Once More” taps an elegiac note: “As spring arrives once more, with airs that haunt, / We turn, gaze backward where our hopes lie beached.” Dolefully she remembers friends who have died: “We turn, gaze back,” as spring’s meaning seasons to “Another Winter”: “Winter is here once more” – repeating and remembering all of her back word glances.

Sarah’s choreography fuses music, dance, and visual art in “Four Cut Sunflowers, One Upside Down” – her response to Van Gogh’s painting: “a last dance on the way / to somewhere else.” Her music plays out in “Like

Shadows on Glass” or in “Shadows in Springtime” where she dances with her grandson from a distance of six feet to the rhythm of “Virus Time.” These rhythms may be more pronounced in poems dedicated to Gerard Manley Hopkins where she transforms his sprung rhythms. Consider her sonnet, “On Reading Hopkins’ ‘My own heart let me more have pity on’…” She rhymes lit, flit, lift, and wit “In a dark vale, a lively mile lit / By a long-dead poet – the forms, forms unforeseen / God’s smile can take!” She illuminates the veil covering her precursor’s windhover or Robert Frost’s sonnet “The Oven Bird” with her own “sonnet’s sheen,” which captures “the swift flit / And swoop a goldfinch makes.” This poem’s final word “lift” refers not only to bird flight and elevated spirit, but also to Sarah’s borrowing from Hopkins.

“Invocation,” the poem that immediately follows the Hopkins poem, invokes “Hope” in a time of despair, and adds “lilt” to earlier tilt and lit – “with her soft Irish lilt (hope like that lilt.” Stanza after stanza lists hope and likens it to a sentence underscored in a borrowed book or a tug on the line. Back, lit, lift, lilt, and keep form an essential part of Sarah’s aesthetics.

The second part of the book, “In the Wilderness,” turns from hope to despair. This long poem begins with “Scroll backward to before, if you can find the spot. / Play back the last ride home with unmasked faces.” There is a biblical backdrop in the scroll and wilderness of “Numbers,” while the title of the first poem, “Last Call,” invokes T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” After scanning her lit horizon, she muses: “Doubt can kill faith. But it can also / give birth to it. A paradox.” This paradoxical poem through urban wilderness and pandemic features a protagonist – tatterdemalion man – an assorted and accumulated figure of Covid’s rag and bone shop. The poet believes in a toddler who sits on pavement “to see who’s seen,” and whose eyes echo “Back to the sea! shouted the brave puppet.” The second poem in this series, “The Fiddler,” personifies doubt and poses the question, “How far back would we have to turn back the clock / to be able to be happy in the old ways?” Through the pandemic she turns back the clock to her “generation in the woods.” God is the “backbone” of this world. Out of her peripheral vision something glides by, “glides / back and forth, insistent.” In wood and word, the fiddler insists on “back” and doubt. The Forager in the next section searches for biblical traces: “Is there a way / to plug ourselves back in to The Eternal?”

Section IV, “Once I Had,” continues to probe Doubt through Rainer Maria Rilke, William Carlos Williams, and Wallace Stevens’s blackbird: “Doubt, like a blackbird whistling on my shoulder.” Sarah looks back over her shoulder towards her precursors. She looks at January sun: “The sun like a stranger in a jaunty hat, just come back from Away.” In this broken time the fiddler returns: “She’s back.” Doubt resumes in the next section, “A Beam,” as a Juggler throwing silver balls in the air, each one a question – “Keeping them all in motion.” In this long poem Sarah juggles questions and keeps parts of the pandemic in motion. Hope in the form of a vaccine against the virus: “all sleeves rolled / back for the boost.” In this contemporary battle against a pandemic, her epic looks back, keeps faith and doubt in suspension, and lifts her characters from the soles of shoes to hopeful souls sheltered in the shadow of winged wilderness.

About the Author

Poet, writer, literary editor, and musician, Robyn Sarah has lived in Montreal since early childhood. Her writing began to appear in Canadian literary magazines in the 1970s while she completed studies at McGill University and the Conservatoire de musique du Québec. Her tenth poetry collection, My Shoes Are Killing Me, won the Governor General’s Award in 2015. As well, she has published two collections of short stories, a book of essays on poetry, and a memoir, Music, Late and Soon (2021), that interweaves her youth as a professional-track clarinetist with her return at fifty-nine (after a lapse of thirty-five years) to the piano teacher who was her life mentor. From 2010 until 2020 she served as poetry editor for Cormorant Books.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

Publisher : Biblioasis

Publication date : Sept. 2 2025

Language : English

Print length : 112 pages

ISBN-10 : 1771966866

ISBN-13 : 978-1771966863