Northern Lights, Ma Peinture c’est l’hiver

Michael Greenstein reviews “Winter Count: Embracing the Cold”

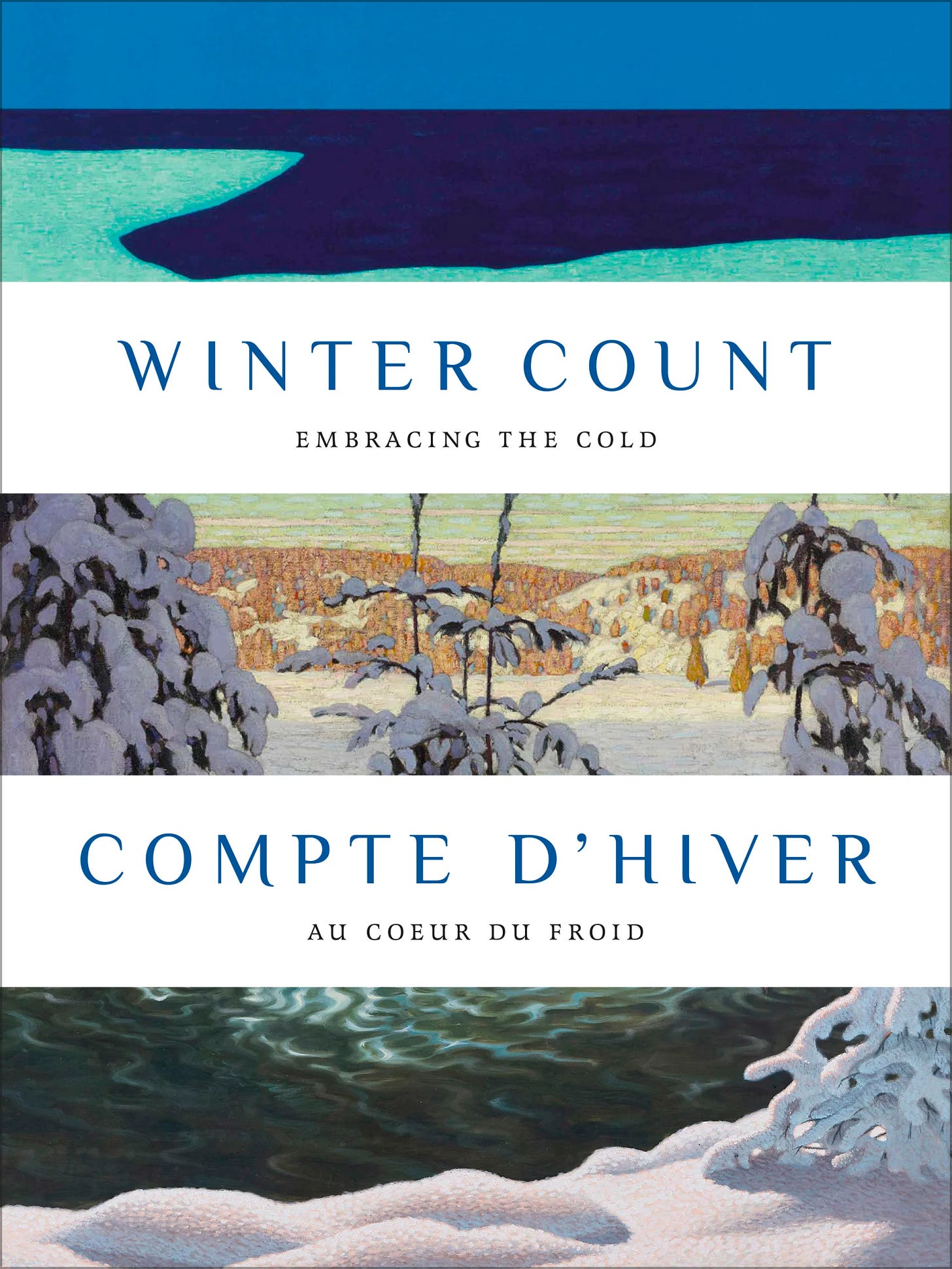

Winter Count: Embracing the Cold, the title of this lavishly illustrated book from Goose Lane, refers to a Lakota (Saskatchewan) tradition of visually recording each year’s most significant events onto animal hide or cloth. These winter counts serve as a means of survival through storytelling and community bonding. Winter Count balances painting from Indigenous, settler, and European artists to offer an overview of the North and to embrace the aesthetics of snow and ice.

Anne Savage’s “April in the Laurentians,” 1922-1924, hovers between winter and spring as if the snow grounding gives rise to green growth, hibernal reluctantly yielding to vernal in the cruellest month of the year. Each painting in this bracing collection of cold becomes a kind of hibernaculum, a resting place for contemplating frozen stasis and melting motion from Scandinavia to Canada.

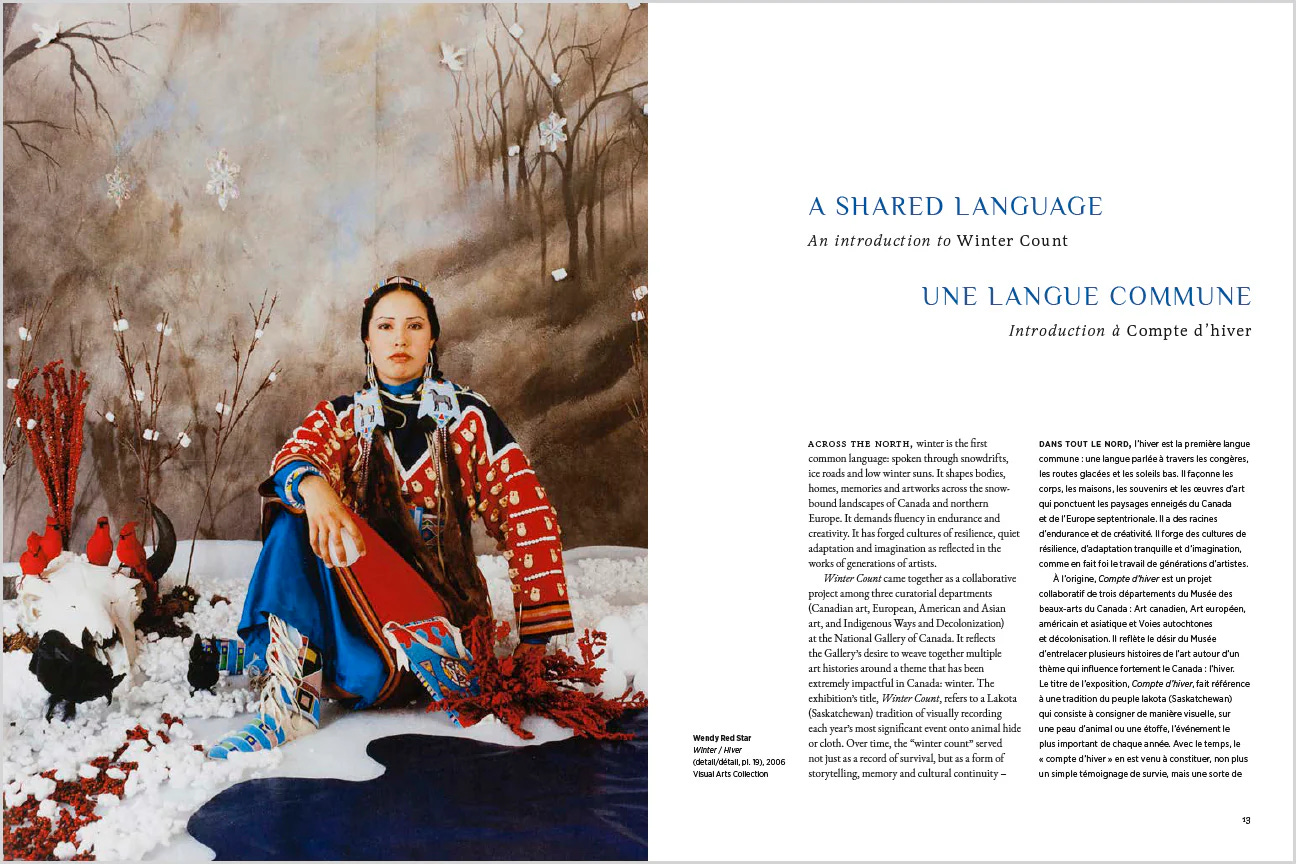

Jean-François Bélisle offers a useful Introduction to the shared language of northern artists. His essay is framed by Wendy Red Star’s “Winter,” 2006, which foregrounds the artist in Indigenous clothing holding a snowball in one hand to subvert stereotypes. She stares defiantly at the viewer, clutching the artificial snowball that participates in the contrasting red and white colour scheme from artificial cardinals to scattered snow. A faded, colourless forest in the background hints at hidden history in contrast to the bright moment of Red Star’s presence. The four cardinals sitting on top of a buffalo’s skull suggest historic hierarchies levelled by the snowball waiting to be thrown playfully and seriously. She and her cardinals sit on snow, blur the forested background, and lay claim to the landscape: The feminist eye of the sitter meets the eye of the beholder, and as in trompe-l’oeil, there is more in the encounter than meets the eye. Her bold red and white colours deconstruct racial profiles as well as American and Canadian flags.

If Red Star’s “Winter” offers one side of the season’s shared language, then Harald Viggo Moltke’s “Iceland 8,” 1899 offers another. A cosmic sweep of green streaks across a dark sky. This comet-like force from above contrasts with the land mass of snow, frozen land and water. This oil on canvas highlights the turn of a century and the tension between stillness and motion.

Yet there may be other ways of embracing the cold and counting winter. Curator Sarah Milroy comments on Margaux Williamson’s winter interiors: her “paintings seem to live and breathe their Toronto milieu: those walls of brick, those dark nights of winter in which one sketches indefinitely inside.” Her “great indoors seems to reflect, too, the experience of northern people, sequestered from the elements for half the year.” Just as the season may be internalized, so too the boundaries of trompe l’oeil may be blurred between realism and the planes and varieties of representation. Fellow curator Jessica Bradley’s remark tilts canvas and eyes to match the trompe-l’oeil characteristic: “Margaux Williamson’s work resides in the real world without allegiance to realism, and this, after all, is what painting can achieve: a way of seeing reality anew, a way of considering its simultaneous familiarity and strangeness.” Fixed and fluid dimensions deceive the eye in more than one way of captivating winter.

Wahsontiio Cross’s and Jocelyn Piirainen’s essay on Indigenous Reflections in winter is bookended by Pudlo Pudlat’s “Winter Bird,” 1984 and Kent Monkman’s “Charged Particles in Motion,” 2007. Flowing lines and curves of “Winter Bird” contrast with its frozen surroundings; it does not migrate south, but stays etched, carved, and engrained in winter. Kent Monkman’s painting centres Miss Chief Eagle Testickle in pink and white, wielding a white whip for her dog sled and traditional background landscape. His colour scheme and subject matter echo Red Star’s “Winter” in their portraits of Superwoman’s sleighing power. Six white dogs dressed in pink harness her sleigh, while a settler’s toboggan is upturned. Her mischief tickles his dogs which are misfits in the landscape, as Monkman trick stirs the paint and history’s sled of memory. He charges all his particles in the motion of history, which becomes rewritten and redrawn, lashed and lassoed against hand-me-down narratives. Miss Chief carries off the spoils of trade and plunder, while an Indigenous painted mask under the toboggan winks at the settler’s snowshoes and grounded musket. The puns in Monkman’s heroine’s name extend to his double entendres of colour, shapes, and overturned historical figures, painted with whip and wit.

From a more tragic perspective Duane Linklater’s “wintercount,” 2022 responds to his isolation during Covid and to the discovery of the remains of 215 children found buried at the site of their residential school. He portrays the trauma on hand-painted, dyed, and printed teepee canvas.

Clarence Gagnon’s “The Train, Baie-Saint-Paul,” 1922 frames the settlers’ experience. The sheer force of his brown train billowing brown smoke contrasts with the cleaner force of white snow and a green hitching post in the foreground where a brown animal is tethered, a mere footnote to the approaching behemoth of a locomotive. Katarina Atanassova’s fine discussion of settlers’ art includes Cornelius Krieghoff, William Kurelek, Charlotte Schreiber, and the shift from realism to Impressionism by the end of the nineteenth century. James Wilson Morrice’s “Winter, Paris,” 1895 displays the influence of the Impressionists on the Canadian sensibility. Atanassova covers the Group of Seven and the Beaver Hall Group in Quebec. Kathleen Moir Morris’s “Byward Market, Ottawa,” 1927 reveals the challenges faced by artists painting en plein-air. Her colourful canvas aligns horses, people, and buildings, as if frozen in time.

Lawren Harris’s “Winter Comes from the Arctic to the Temperate Zone,” 1935 completes this section. Ghostly off-white snowdrifts or temples of ice climb to a peak; behind them blue echoes continue the climb between arctic and temperate regions of the drifting, frozen mind. Fire and ice: like William Blake’s ascending flames of fire, Harris’s vertical pillars of ice gesture toward the sublime, informing cosmic powers – white fingers triangulating against sky-like ice caps. If Escher’s drawing hands reach for dimensions of trompe-l’oeil, Harris’s abstract fingers deceive the eye. His ghostly post-Impressionist columns replace the blue swirls of van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” as he navigates between arctic and temperate zones of colour. Commenting on Harris’s work, Northrop Frye goes beyond the second and third dimensions of trompe l’oeil: “A picture has to suggest three dimensions before it can suggest four, before the object can become a higher reality by becoming also an event, a moment suspended in time.” In short, the eye deceived by dimensions of abstraction, surrealism, or Impressionism.

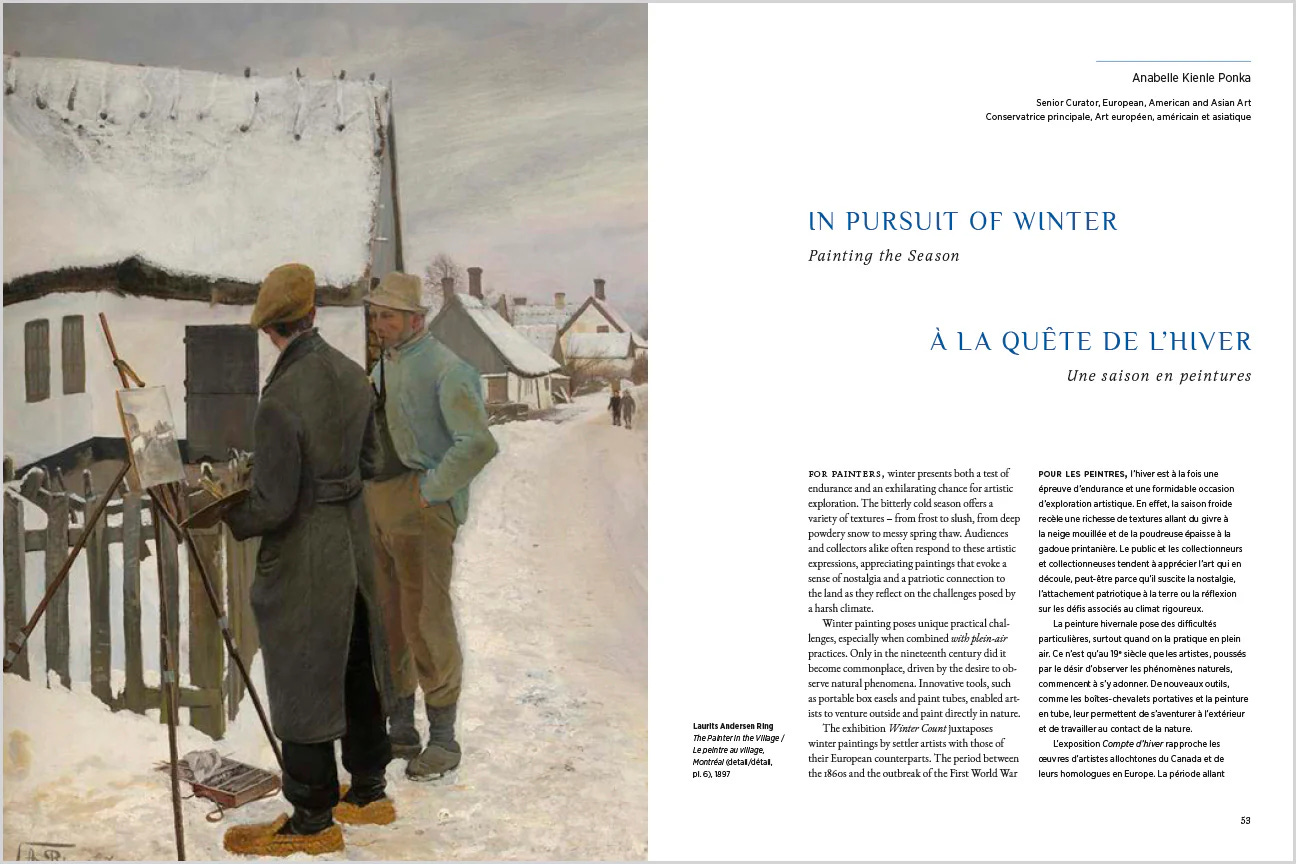

The final essay by Annabelle Kienle Ponka is framed by Laurits Andersen Ring’s “The Painter in the Village,” 1897 and Wassily Kandinsky’s “Winer Near Urfeld,” 1908. Maurice Cullen’s “Sunny Day, Ice Cutting, Montreal,” 1920 offers the heaviness of dark brown horses and human figures against weighty blocks of ice. Krieghoff’s “The Blizzard,” 1857 centres a brown horse between people in a red sled on one side and an approaching figure with a dog on the other. The earliest painting belongs to Bruegel whose “Hunters in the Snow,” 1565 foregrounds brown hunters and their dogs against a background of miniature skaters on ice. Kandinsky’s “Winter Near Urfeld,” brushstrokes thick colours in abstraction, their impasto extending trompe-l’oeil’s frame of reference. Each of these snow fugues contributes to painters’ eye-deceiving counterpoint between realism and abstraction of winter deserts with snow replacing sand.

Vive le nord, oui l’hiver, we the north mindful of winter. No Canadian coffee table would be complete without a copy of Winter Count.

About the Authors

Katerina Atanassova is Senior Curator, Canadian Art, at the National Gallery of Canada.

Wahsontiio Cross is Associate Curator, Indigenous Ways and Decolonization, at the National Gallery of Canada.

Anabelle Kienle Ponka is Senior Curator, European, American, and Asian Art, at the National Gallery of Canada.

Jocelyn Piirainen is Associate Curator, Indigenous Ways and Decolonization, at the National Gallery of Canada.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published extensively on Victorian, Canadian, and American Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe

Book Details

Publisher : Goose Lane Editions

Publication date : Jan. 20 2026

Edition : Bilingual

Language : English, French

Print length : 208 pages

ISBN-10 : 1773104926

ISBN-13 : 978-1773104928

A poetic and evocative celebration of winter, capturing the quiet beauty and luminous charm of the season through art and words.

Marvellous. A story about a Lakota Winter Count was aired on https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved a couple of days ago!