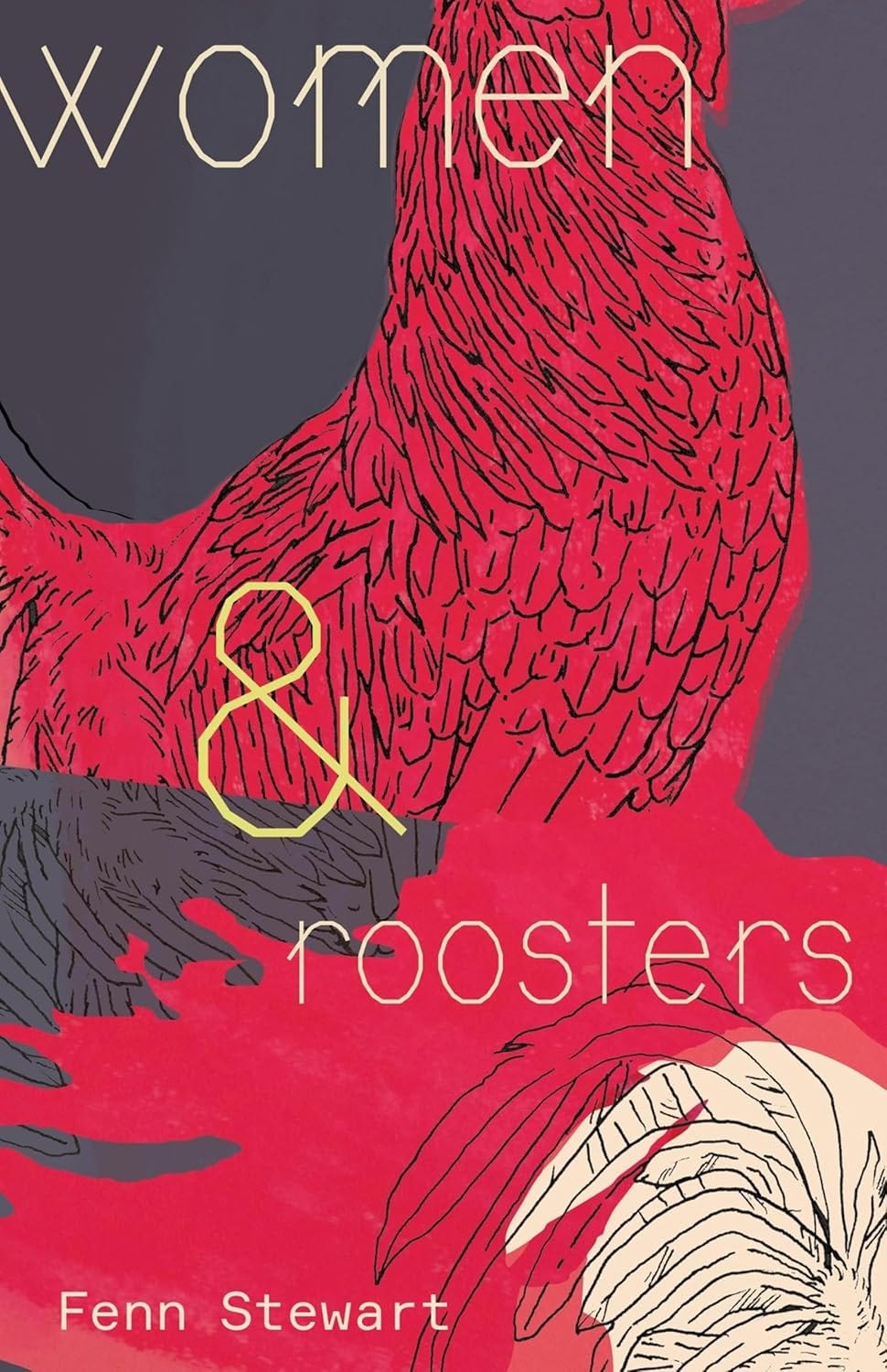

Women and Roosters by Fenn Stewart

Reviewed by Dawn Macdonald

“And if I only could,” sang Kate Bush on her 1985 hit from The Hounds of Love, “I’d make a deal with God, and I’d get him to swap our places. I’d be running up that road, be running up that hill, with no problems.” I know this song plays in Fenn Stewart’s head sometimes, because she’s included it in the playlist she’s assembled on the publisher’s website. Furthermore, I checked the playlist specifically to see if this song was there, because it started playing in my head when I read these lines on page 35 of her book length prose poem, women & roosters—“About a month later (still a whole year before I got sick), I was running up this same exact hill—(I used to run up this hill all the time, but I can’t do it anymore), and I said to you, “Isn’t there a risk, if we carry on like this?” And you shrugged and said, “Probably, yeah. But it’s a risk worth taking,” and I was pleased all over like a happy dog, but I also knew that you had no idea what that meant, what it would mean. And you still don’t, really.”

The Kate Bush song is enigmatic. Bush has said it’s about the idea of a man and a woman changing places, getting to “feel how it feels” from each other’s perspective. The Fenn Stewart character, if I can call her that, in women & roosters has been burned, hard, though we don’t know exactly what happened. We just know there’s someone, a man, whom she can’t stop talking to in her head—replaying conversations like the one above, adding commentary, telling him how it’s been for her—trying to get him to experience the relationship from her perspective. In an aside to the reader, Stewart explains, “this is the closest I’ve ever been to unrequited love // it isn’t great // it’s actually pretty bad” and turns to address the absent beloved with a vivid image, “without you I’m like a three-legged stool without one leg and / then without the other one too so just the one leg, not two- / dimensional enough to rest like a penny does when you drop / it, and it spins for a while, but then it settles down—I can’t settle down”.

This restlessness is reflected in the shifting setting, as Stewart moves between rural and urban spaces. She hunts crabs on the beach, walks along the road, sits on the porch watching the birds that eat thistles, but her brain continues to generate imaginary conversations. “I want to say I marvel at how sad I am without you: // I marvel at how sad I am without you // sad like a thistle-head entirely eaten by a bird; // no, sadder, like a thistle-head completely left uneaten // sad like a black-and-yellow thistle-eating bird eating thistles”.

The voice is raw but, as is evident in the quotations above, not without a sense of humour about the ways in which longing can turn a person into a parody of themselves. Stewart is sharply observant of inner states that tint perception of her surroundings, how birds and thistles seem to compete for the prize of most-saddest under her troubled gaze. Later in the book, replaying scenes in her mind, she writes, “I stand up quickly and I walk to you // you’ve turned, and I can’t see your face // (no, that’s not right // I’ve never even seen you turned // I’ve never even seen you from the back: I wouldn’t even know / you from the back)”. Now it’s unlikely that she’s never seen her lover from the back, but there’s an emotional truth to this—in memory, a significant love seems all face, always facing us, always eye to eye. Also, perhaps, the intense nature of an incomplete relationship, one where the participants weren’t so much in each other’s daily lives of grocery shopping and washing dishes, but rendezvoused in compressed intervals. Stewart is an unreliable narrator in this sense, telling the emotional experience of perception rather than, necessarily, the truth.

The consonance between actual and inner worlds can become a source of added pain to the sufferer. “I wish all these things didn’t keep happening,” she writes, “all these not-metaphors that look like metaphors, so unseemly.” An unrequited love happens so much inside the mind; is it possible to have such a love free from the literature of love? From the literature of the body, of its animal nature? From the literature of nature? Women and roosters are said to have one quality in common; according to the Greco-Roman physician Galen these two are the only kinds of creatures who don’t feel sad after sex. Well, maybe not right after. But until we can swap places, like in the Kate Bush song, there’s no way of knowing all that’s in the lover’s heart.

About the Author

FENN STEWART is the author of three chapbooks and the poetry collection, Better Nature, which was longlisted for the 2018 Gerald Lampert Memorial Prize. A former editor of The Capilano Review, she continues to serve on the magazine’s editorial board. Stewart holds a PhD in social and political thought, and teaches literature and writing at Capilano University. She lives with her kids in Vancouver, B.C., on unceded Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), xʷməθkʷəỷəm (Musqueam), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) territories.

About the Reviewer

Dawn Macdonald lives in Whitehorse, Yukon, where she grew up without electricity or running water. She won the 2025 Canadian First Book Prize for her poetry collection Northerny. She posts weekly at Reviews of Books I Got for Free or Cheap (on Substack), as well as reviewing for journals and for The Seaboard Review of Books.

Book Details

Publisher : Book*hug Press

Publication date : Oct. 28 2025

Language : English

Print length : 79 pages

ISBN-10 : 1771669470

ISBN-13 : 978-1771669474