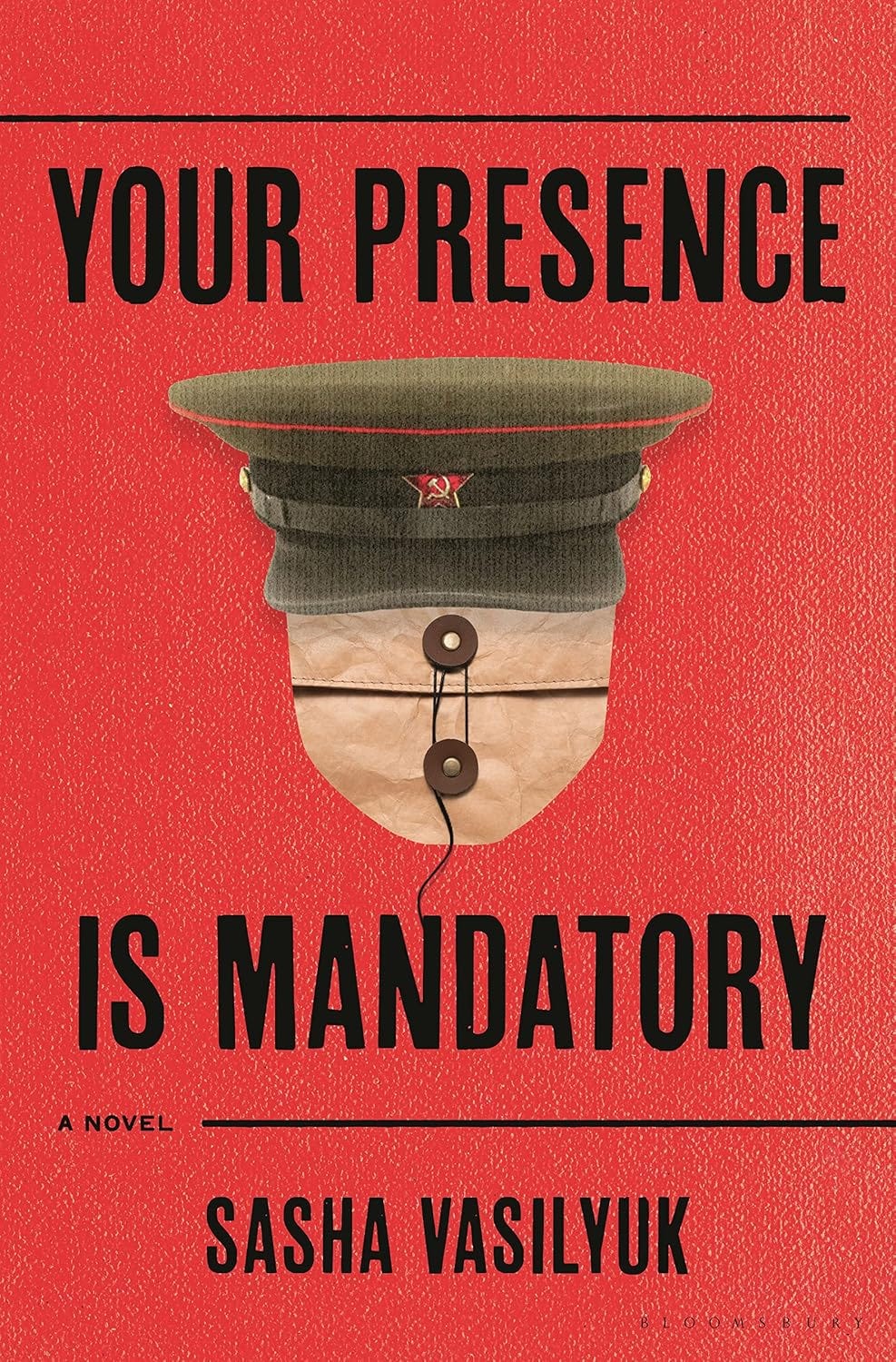

Your Presence is Mandatory by Sasha Vasilyuk

Reviewed by Olga Stein

Had a novel like Your Presence is Mandatory surfaced in the Former Soviet Union 20+ years ago, its author would’ve been harassed and intimidated by the ‘morality’ wing of Vladimir Putin’s regime. Any author wishing to address frankly and factually soldiers’ and veterans’ dire circumstances during and after the Great Patriotic War while Stalin was alive, or in the decades that followed his passing, would have been found guilty of sedition. Political dissidents, who laboured in the aftermath of WWII to expose the staggering incompetence of Stalin’s military brass, the callous disregard for their troops’ welfare, and the government’s unwarranted policy of indicting repatriated POWs for collaborating with their German captors, risked, like the writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, internal exile and forced labour in one of Siberia’s infamous gulag camps. For that matter, any Soviet nonconformist author could, like the Jewish modernist Isaac Babel, wind up being arrested and sentenced to death by firing squad on trumped-up charges of espionage and terrorism.

“Your Presence is Mandatory centres around several false narratives—most notably, the ideologically-driven and mollifying distortions of national history produced by the Soviet leadership during much of the 20th century.”

Sasha Vasilyuk, whose mother is Jewish, came into the world more than three decades after Stalin’s passing, and was able to leave the Former Soviet Union (FSU) for America as a teen. Vasilyuk grew up in California, studied journalism, and built her literary career in the US. This is most fortunate because Your Presence is Mandatory centres around several false narratives—most notably, the ideologically-driven and mollifying distortions of national history produced by the Soviet leadership during much of the 20th century. In her fine, meticulously researched literary debut, Vasilyuk uncovers other damning accounts, the kind that would have irked government-appointed culture minders of former times. Let me restate that she is fortunate to have penned this novel (an irony in itself) outside current-day Russia.

“In the Soviet Union,” Vasilyuk writes in her Author’s Note, “where history was constantly gilded and where people never reckoned with the past the way Germans had, restoring the truth is both tricky and vital.” Historians, culturalists, and students of Soviet literature, of its samizdat authors especially (i.e., those forced to publish their work underground for fear of government reprisals), might think this obvious or an understatement. Yet it’s a necessary reminder for all who watched Putin and his commissariat continue to spin their rationale for invading Ukraine and persist with a war that has already devastated and displaced an untold number of people. Crucially, not unrelated to these ex-apparatchiks’ claims, is the larger historical context, which brims with treachery and falsehoods, and which readers everywhere should understand.

To fully appreciate Vasilyuk’s novel, a reader must grasp a number of unadorned truths about Russia’s past: The Soviet Union didn’t stop being an expansionist empire, even after the communist revolution of 1917. The forced collectivization and dekulakization of Ukrainian farmers, which resulted in a famine that killed millions in Ukraine, was merely the first chapter in Soviet imperialist aggression. Putin’s assumption that Russia is entitled to dominate Ukraine is rooted in this lamentable history. Second, the ‘communism’ the Soviet government imposed on its own people, and on the nations it subjugated, was a sham master narrative it persistently wrapped in the language and symbols of universalism, and social and economic equality, while deflecting scrutiny from its ruthless authoritarianism.

These points are especially pertinent if one is trying to situate Vasilyuk’s novel amid certain kinds of Soviet and post-Soviet writing—the former usually produced through Samizdat (more voluminously in the second half of the 20th century), the latter, overwhelmingly by those who managed to immigrate to the West in the past 50 years, including the US and Canada. Poetry and prose written by these very same immigrants often reflects on their past lives, and is invariably critical of the myriad forms of oppression to which they, as Russian Jews, were subjected. In some ways, then, it seems as if a novel like Your Presence is Mandatory was destined to be written by one of the scores of gifted immigrant writers from the FSU. In other ways, as I explain by means of the brief retrospective below, its diegesis is both unanticipated and intriguing.

Let me begin by stating a pertinent fact: in the USSR, what might or might not be made available to the general public was always determined by the government. This is germane because the art and literature it sanctioned, its rigid insistence on socialist realism in particular, spawned numerous ‘underground’ or dissident movements, which gained recognition and currency during the Soviet era and formed canons or, more precisely, anti-canons of their own. Your Presence is Mandatory exposes or affirm truths that were suppressed or deliberately omitted by Soviet officialdom, or that were never voiced due to fear of state retribution. These and other aspects draw the novel into that same history of Soviet counter-culture.

“Double culture,” the term ascribed by literary scholar Yury Lotman, and cultural historian Boris Uspensky, to the phenomenon of dissent by way of art, captures the Soviet-era reality of official and unofficial publishing (and discourse more generally). Unofficial (usually banned) literature sought, among other things, to disrupt the linearity and simplicity of authorized Soviet storytelling and provide counter-narratives to established versions of events, together with distorted depictions of national sacrifice and resilience. It was this, the government insisted, as well as the heroic “new Soviet man” — his patriotic devotion to a morally-superior mother Russia — that brought about victory over Nazi Germany.

I recommend the recently published Reinventing Tradition: Russian-Jewish Literature Between Soviet Underground and Post-Soviet Deconstruction by Klavdia Smola to anyone interested in learning more about the ways “double culture” manifested in the FSU. A sociologist and literary scholar, Smola has made a detailed study of late- and post-Soviet fiction, surveying and analyzing the poetics of “literature [that] evades the language of dictatorship and overcomes it.” Smola helpfully outlines the stakes that obtained for Soviet-era non-conformist culture producers: historical accuracy and political transparency; and, for Jewish authors, as with other ethnic minorities in the FSU, the recovery of collective and personal identities.

Referencing political theorist and authority on Soviet national literatures, Evgeny Dobrenko, and his book, The Metaphor of Power: Literature of Stalin’s Epoch in Historical Light (published in 1993), Smola writers: “Dobrenko explores Soviet cultural discourse as a ‘metaphor of power’…and interprets the concepts of myth, following Roland Barthes, Ernst Cassirer, Iurii Lotman, in relation to the communist art canon…as a metaphorical transformation or distortion of language.” Significantly, according to Dobrenko, “[t]he politically charged substitution of reality with symbols has an inherent historical teleology that gives the created figures of the canon a symbolic, abstract, and hyperbolic character.” In socialist realist art, which was privileged and promoted by the Soviet government, the everyman hero “becomes the iconography of ideological forms, the pure naturalization of the symbols of the language of power” (Dobrenko, pp 32-9, 42). Vasilyuk turns this prescribed socialist realism aesthetic on its head.

With Your Presence is Mandatory readers can see what happens when the “common man” protagonist’s realistically rendered war-time experience refutes state-approved narratives of the war and disrupts their ideological grammar? For the hero (and reader), the rhetorical spell of communist allegory and symbols is broken. What remains is the stark reality of Stalin’s purges, the KGB’s sordid machinations, and veterans’ struggles either to survive post-war imprisonment in labour camps, or shield their families from truths they fear will tarnish their lives.

At the outset of Vasilyuk’s novel, Yefim Shulman is an eighteen-year-old private serving as an artilleryman at the Red Army’s base in Lithuania. Thoroughly indoctrinated, he has faith in the Communist Party’s declared mission of lifting up every citizen irrespective of ethnicity or economic status, and in the competence of the military leadership under Stalin. Soon after, the German army stages a surprise attack, and Yefim witnesses death and destruction during one of its aerial bombardments. Failing to outrun the invading Germans, he becomes a POW and is himself made to endure indescribable hardship due to the Soviet Union’s failure to sign the Hague and Geneva Conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners of war, and because the NKVD and Red Army adjudged captured Russian and Ukrainian soldiers as defectors or traitors. After the war—because disillusioned and clear-eyed—Yefim falsifies his service history to avoid the NKVD’s infamous filtration camps. He keeps the fact of his captivity in Germany hidden for decades more—from the authorities and from his wife and children.

Young Shulman, along with his close Ukrainian friend Ivan Didenko, fellow artilleryman and survivor of the Holodomor, are the valiant every-men of Soviet-era literature. However, their values diverge from those of the Soviet state and the humanist teleology it purports to represent. Significantly, by bearing witness to the negligence and unabating brutality of the regime, Yefim, Ivan, and Sergey Nikonov, an officer whom Shulman befriends while imprisoned in Germany, are pitted against the state, its deranged apparatus, and the political nostrums it hides behind.

Your Presence is Mandatory is comprised of two chronologies or narratives: one relates Yefim’s wartime ordeal, his years of being trapped in Germany’s small towns and forced to work as an ostarbeiter, until he’s able to rejoin Soviet troops advancing on Berlin; the second portrays the post-war years, and involves Yefim, his Ukrainian paleontologist wife, Nina, and their children Vita and Andrey. Vasilyuk toggles between Yefim, Nina, and their children’s points of view to evoke the couple’s offbeat, though mostly contented marriage and family life in Ukraine. Later chapters introduce the Shulmans’ grandchildren, while keeping readers informed about changing circumstances in Ukraine and Russia. The narrative ends with a description of the political unrest in Donetsk of 2015, eight years after Yefim’s passing and Nina’s discovery of the letter containing a confession Yefim had composed for his KGB interrogator.

Vasilyuk handles both narratives and the shifts between them well. The psychological realism, effected by Vasilyuk’s solid grasp of character and attention to minute details, captures both the horrors of Shulman’s war experiences, and the texture and nuances of Soviet-era husband-wife relationships. Of note is that chapters that follow Yefim after the war provide a glimpse of the toll that hiding his ostarbeiter past takes on his marriage. Yefim, a busy geologist and land surveyor, cherishes Nina, but he’s convinced he can never divulge the truth of his captivity to her or their children. They would be deeply ashamed, he believes, if they discovered that he wasn’t a war hero, contrary to what he’d led them to believe; it would destroy them to learn that he was a slave labourer who aided, however unwillingly, the enemy in their war effort.

Yefim visits Nikonov on the sly. Having served his NKVD-decreed sentence in a gulag and now settled in a nearby town, Nikonov is the only one who knows what actually happened because he too had been captured. Meanwhile, despite the love and respect she feels for Yefim, Nina is aware that the closeness she longs for in their marriage is nearly always and unaccountably missing, even after twenty-five year of living together: “She looked at this husband of hers,…whom she knew intimately yet not at all.” Years later, having discovering Yefim’s confession, Nina reflects:

[She] had understood why Yefim had hid such a thing. Having had her own documents marked with “lived in [German] occupied territory,” she knew the stigma that followed him. But even though she understood his reasoning, she wondered if it had been worth it….The letter made Nina wonder how much his past was responsible for the wall that had always seemed to stand between them.

Vasilyuk based her novel in part on her Jewish grandfather’s harrowing and never-disclosed story. He became a POW in Germany early in the war. As a Jew, he managed to survive only by taking on the identity of a Russian soldier, who was killed in a Lithuanian forest by advancing German troops. Later, Yefim had to labour as an ostarbeiter in Germany (foreign slave worker), and after the war, he was a tight-lipped veteran hiding the fact of his five years in Germany from the KGB and from his family.

Your Presence is Mandatory has already been translated into Italian, German, French, Finnish, and Brazilian Portuguese. In addition to other honours, it garnered Vasilyuk the California Book Award for Debut Fiction and the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. These prize-related endorsements are fully merited. Vasilyuk’s historical research is exemplary, and her writing is well fashioned, evocative, and perceptive. More significant still is the novel’s serious subject matter and unambiguous relevance to world-historical and present-day events.

Any reader of Ukrainian descent will grasp the meaning of passages where Nina, now in her eighties, reconsiders her reticence respecting the horrors she witnessed during the Holodomor:

Yefim used to say she told the kids too much, that she needed to be more careful, but maybe it was the opposite….Now her memories of the war and the famine seemed to acquire a new urgency. She had told her kids about the villagers who had died on the streets during the famine, but what she didn’t say was that there were guards who were trying to prevent them from sneaking in to find food. A small change with big implications.

Likewise, any reader with a connection to POWs who managed to evade Soviet efforts to forcibly repatriate their former military personnel and other nationals in the wake of WWII, as per the terms of the Yalta Conference (February, 1945), will understand the significance of the novel’s references to the punishment and oppression of soldiers held captive in Germany, like Nikonov, as well as Ukrainian civilians, like Nina, who were subjected to German rule in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine (the Reich Commissariat of Ukraine), the territories occupied by German forces during WWII.

Finally, Your Presence is Mandatory should speak to anyone who has glimpsed Russia’s Victory Day parades, staged by the Kremlin every year on May 9, including its recent, 80th anniversary edition, with Putin at the helm. The ceremonial fanfare—bombastic and prosaic at once—masks the factual record of Russia’s WWII losses: the the dead numbered 26 to 27 million. Vasilyuk and her novel remind us that the latest parade, dishing out propaganda related to the “special military operation” in Ukraine is merely one in a long string of misleading narratives. Once again, Russia is trying to sell its citizens on a reckless war of aggression. Yet again, state-managed hype and spectacle conceal a cataclysm of its own making, a war it can’t win.

About the Author

Sasha Vasilyuk grew up in Ukraine and Russia before immigrating to San Francisco at the age of 13. Her nonfiction has been published in The New York Times, CNN, Harper's Bazaar, Los Angeles Times,and elsewhere. She has won several awards, including the Solas Award for Best Travel Writing, NATJA award, and BAM/PFA Fellowship from UC Berkeley. Your Presence Is Mandatory, was longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize and has won the 2025 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature.. She lives in San Francisco.

About the Reviewer

Olga Stein is an academic, writer, editor, and university and college instructor. She was born in Moscow, the capital city of the former Soviet Union. She immigrated to Canada with her parents as a child, and has lived in Toronto her entire adult life. Stein earned her BA and MA at the University of Toronto. She studied philosophy, political science, literature, and languages. After serving for two decades in medical and literary publishing, including as chief editor of the literary book review magazine, Books in Canada, she returned to academe, and completed a PhD in contemporary Canadian literature and cultural institutions.

Stein has been writing literary essays and cultural commentary for nearly two decades. Since completing her PhD, she has also been writing short fiction and poetry. She has three children. Love Songs: Prayers to gods, not men is her debut collection of poems.

Book Details

Publisher : Bloomsbury Publishing

Publication date : April 23 2024

Language : English

Print length : 336 pages

ISBN-10 : 1639731539

ISBN-13 : 978-1639731534

Works Cited

Dobrenko, E. (1993) Metafora vlasti. Literatura stalinskoi epokhi v istoricheskom osveschenii. Verlag Otto Sagner.

Shlapentokh, Dmitry & Evgenii Dobrenko. “Metafora vlasti: Literatura Stalinskoi epokhi v istoricheskom osveshchenii” [“The Metaphor of Power: The Literature of Stalin’s Epoch in Historical Light”]. Slavic and East European Journal 39 (1995): 304.

Smola, K. (2023) Reinventing Tradition: Russian-Jewish Literature between Soviet Underground and Post-Soviet Deconstruction. Academic Studies Press.