David Blackwood, Myth and Legend, Ed. Alexa Greist

Reviewed by Robin McGrath

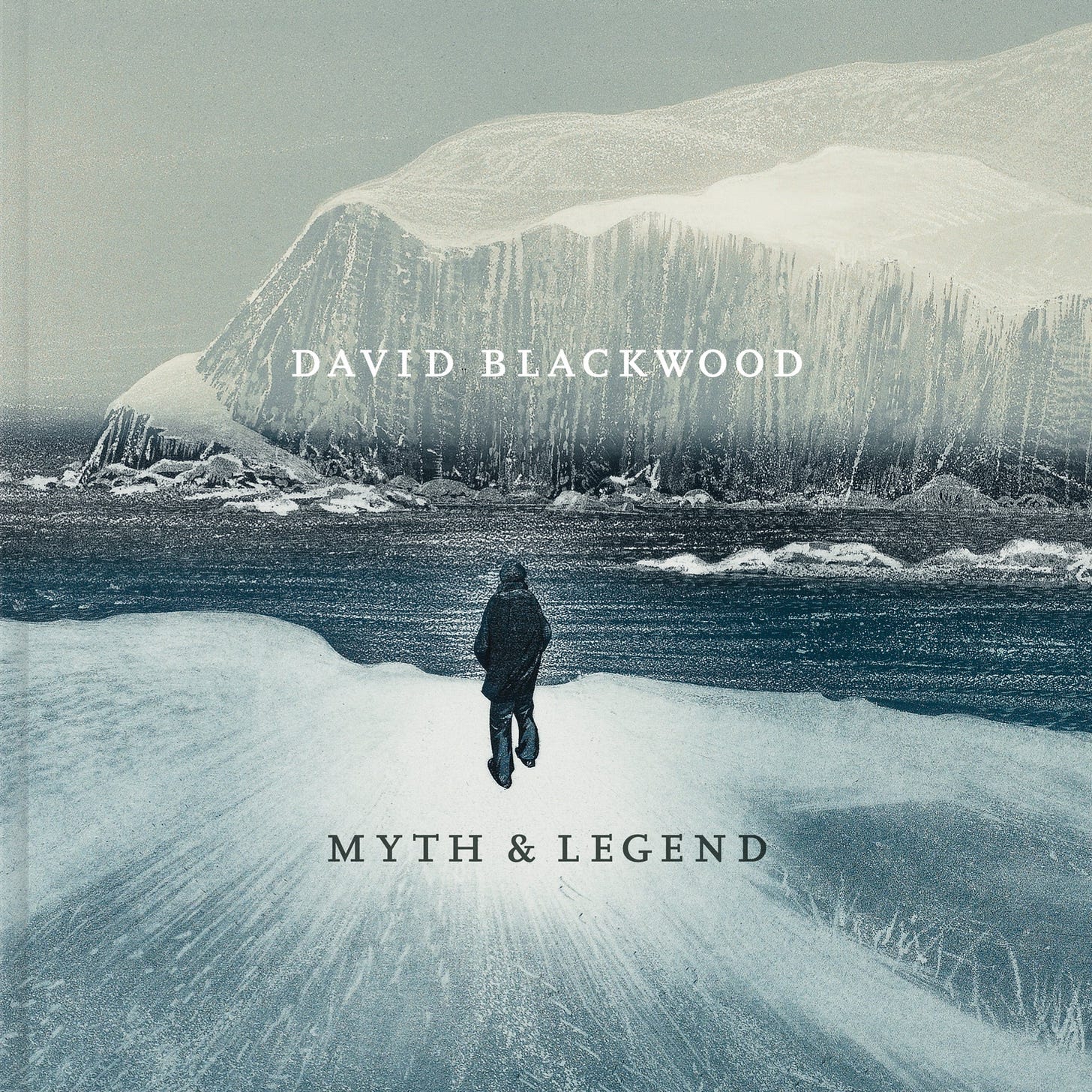

David Blackwood: Myth and Legend is the fifth major book to be published about the work of Newfoundland printmaker David Blackwood, and it is being issued at the same time as a reprint of a previous volume, Black Ice, to mark the Art Gallery of Ontario’s collection of 300 of his prints as well as a significant archival assembly of drawings, diaries, and relevant documents related to his life and works. One of the things that makes Myth and Legend different from the previous books is the focus on the evolution of specific prints, from the initial drawings to the completed, final version of the image. There are, for example, more than twenty reproductions of the print “Wedding on Deer Island,” many of them in full colour, measuring over nine by eighteen inches, which allows viewers to see the progression of the artist’s work, including changes Blackwood made during the process. There are five reproductions of the stages of the print “January Visit Home,” one large and four small, illustrating the changes and additions, both large and small, that the artist made to the work before considering it complete.

To some extent, the title of this book is somewhat misleading, as it is not really about the myths or the legends of either David Blackwood or the subjects of his prints — it is much more about how he made the works, the intaglio process he used to produce his art. A footnote very helpfully draws the reader’s attention to a short documentary film, “Blackwood,” by the National Film Board of Canada. It is less than half an hour long, in which Blackwood not only explains his method but demonstrates it. The film is available without charge on the internet and is really worth viewing, especially for readers who are unfamiliar with print processes.1

In simple terms, intaglio involves etching lines into a copper plate and filling the recesses with ink that is then transferred under tremendous pressure to the paper. Relief printing, which is employed by anyone who has ever used a rubber stamp, transfers ink from the raised surface to the paper. Relief printing can be done using a cut potato, a common eraser, a piece of linoleum, or a much more sophisticated surface such as wood or stone. Intaglio involves engraving acids, waxes, resins, and inks, and generally demands a complex series of proofs and adjustments.

“David Blackwood is now acknowledged as one of Canada’s major artists, but such was not always the case. His methods were thought to be unnecessarily complex, his subject matter limited, his vision narrow, and his palate dark and dreary.”

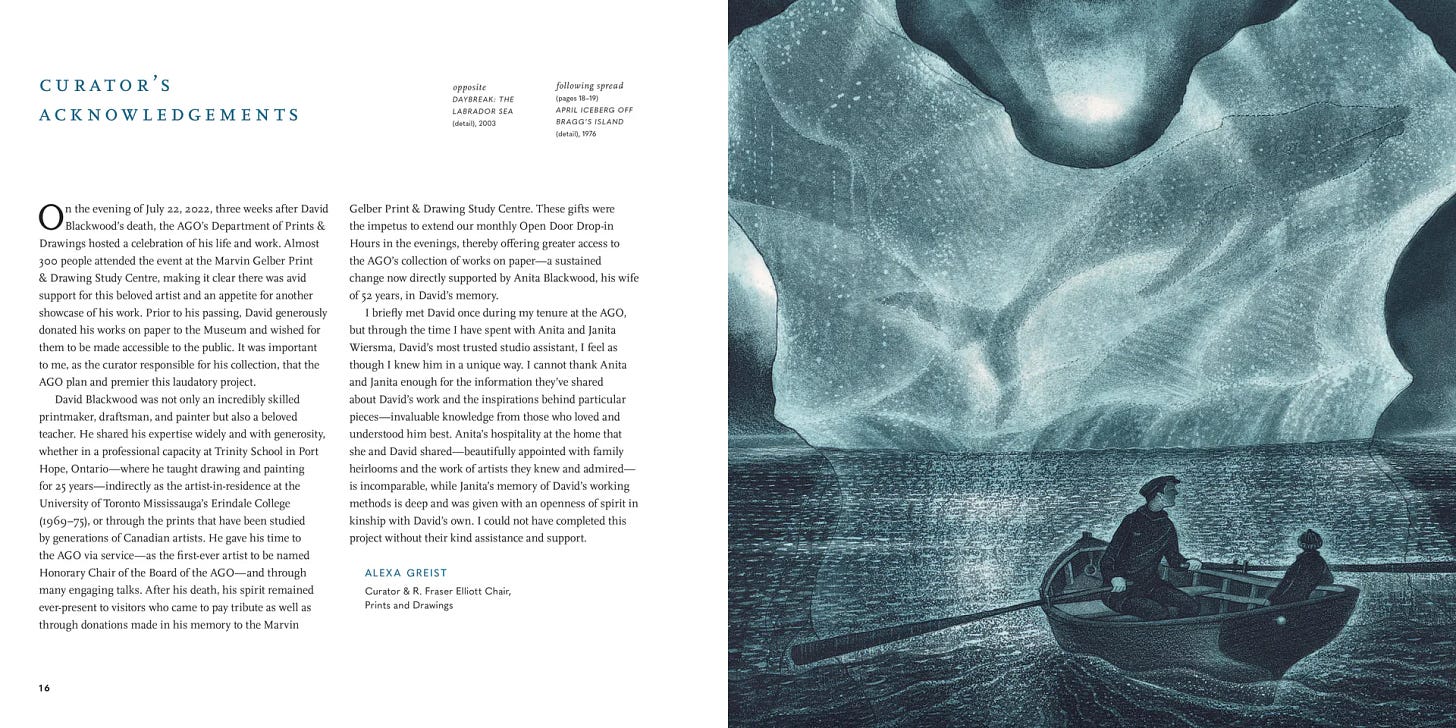

David Blackwood is now acknowledged as one of Canada’s major artists, but such was not always the case. His methods were thought to be unnecessarily complex, his subject matter limited, his vision narrow, and his palate dark and dreary. His colours were mostly blue and grey with only occasional touches of colour, primarily red. Blackwood’s work focused almost exclusively upon the history of outport Newfoundland, with its vast landscapes of ice and ocean, and portraits of the rough, weather-worn people who prosecuted the fishery. Death was never far away, and the rare touches of colour he used were often artificial flowers on a casket, faded wallpaper on a kitchen or parlour wall, or perhaps a lantern, flag, sunset or painted gate.

James Stewart Reaney, writing about Blackwood during the 1980s, noted that Newfoundland musicians and actors at that time were showing “a defiant wit and pluck absent in Blackwood’s art.” He goes on to note that the artist’s huddled figures often faced an indifferent sea, and that “he insists on a grim world-view as if determined to strip away all but the slightest glimmer of optimism.” Such a reading is superficial at best. Blackwood’s work celebrates endurance, survival, heritage, loyalty, and family, all of which emerge from the procession of print proofs illustrated in Myth and Legend. That gleam of a lantern, the flowers in the hat of a woman at a funeral, emerge at the end of the printing process, giving hope to the viewer and celebrating the endurance of the world that Blackwood grew up in.

It is fitting that the publication of Myth and Legend is paired with the republication of Black Ice, because the earlier book gives us the man behind the artist, the history which Blackwood used to create, or recreate, the Wesleyville world he grew up in. Blackwood’s life was not always an easy one. David’s mother, Molly Glover, was a source of much stress to David as a boy. She had married an older man with 5 children, and had a notoriously demanding mother-in-law with whom she could not cope. She was never able to fit into the family or to satisfy their domineering demands. Gough writes that Molly’s temper, which at first turned inward, “began slowly to turn outward.” In Black Ice, Katharine Lochnan records an occasion in which Molly Glover “took a broom to the top of the house and as she descended the staircase, broke every single pane of glass in the windows.” She follows this account with the simple statement “She was taken away and institutionalized,” after which her husband brought the two youngest boys, David and his brother, to live with Molly’s parents on Bragg’s Island.

David wrote in his diary for December 4, 1955, on a page reproduced in Myth and Legend, “My mother who is not very well because of mental health cannot work very well. Many of the pleasures of life are robbed from us because of this; but I cannot complain because of the many things we have that others don’t.” Two prints, “Molly Glover on Bragg’s Island” and “Molly Glover Leaving Bragg’s Island,” both reproduced in Myth and Legend, show Blackwood’s mother as a young woman, running along the shore, as if the hounds of hades were after her, and then one of her standing in the bow of a boat surrounded by a tangle of agitated lines that stretch to the sky, with her two small sons looking on. It is a picture of the hysteria of madness.

Blackwood’s obituary describes him as “soft-spoken, kind, and with a will of steel, and as David McFarlane notes, “it was that will of steel that made him so different from everyone else.” A frequently reproduced photo of Blackwood as a 15-year-old, included in Myth and Legend, shows him in jeans and a leather jacket with a James Dean haircut and stance. Nothing in the photo suggests the calm, mild, thoughtful Methodist mind that dominated people’s perception of him as an adult. One reproduction of the photo identifies the setting as “at school pond May 1956,” apparently written in his own hand. A story told by a woman who acted as Blackwood’s teenage studio assistant when he was a visiting artist at Memorial University around 1966 gives insight into that photo and that location.

Blackwood had a summer artist’s residency at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s, and as it drew to a close, faculty member Don Wright organized an open house in the art studio to allow the general public to get to know the artist and his work. Towards the end of the evening, a quiet, reserved man entered the room, and after some hesitation, went up to Blackwood and began speaking to him in a very intense way. After several minutes, the two shook hands and the stranger left. The girl noticed that Blackwood seemed somewhat shaken by the encounter. “What was that all about?” she asked Blackwood, teasing him a little. Much to her surprise, he spilled out a story.

Apparently, as a teenager, David Blackwood wasn’t always the meek and mild character he later appeared to be. During school one morning, he said or did something that enraged his teacher, who came after him, possibly with a strapping in mind. Fifteen-year-old David wasn’t about to submit peaceably, and instead took off out the door with the angry teacher in pursuit. Like a lot of the boys in the class who had started the day helping their fathers with the fish, David was wearing rolled-down hip waders, and as he ran, he reached down and pulled them up, headed straight for the pond behind the school, and waded in. By this time, the teacher was so furious that, despite his suit and dress shoes, he followed the boy into the water, grabbed him, and gave him a good shaking, breaking his arm in the process. The Blackwood family was not without status in the community and the teacher was either disciplined or dismissed.

The mysterious visitor to the open house at MUN was, of course, the guilty teacher. He had come to apologize to Blackwood and to say how terrible he felt that, in his anger, he had inflicted an injury on him that might have damaged or destroyed the boy’s great artistic career. Had this been the case, the man said, he would never have forgiven himself. “It was my fault,” Blackwood confessed to his assistant. “I was awful to him.”

The photo of Blackwood “at school pond” is reproduced in Myth and Legend, in the section on the Blackwood archive. The picture is pasted into the back of his journal for January 1955 to December 31, 1958, and next to it, in barely decipherable writing, is a brief verse that appears to say “O foolish boy who’d spend his time at play, who’d give and love and sacrifice but for a day. O foolish boy who’d waste his precious schooltime, who’d fool with a girl but for a [?], and spoil a future O what a price to pay.” The verse is signed D. B. March 19, 1957.

Around the time this incident occurred, Blackwood was in the process of determining that his life would be dedicated to art, not to the family fishery. When he was fourteen, his father gave him a fishing boat, and the following year, he and a friend used it to fish lobster, but it was not what he wanted to do. Katharine Lochnan records that David was really put out by the gift. “What was I supposed to do with this thing? Here I was hating school, and wanting to draw and paint all the time.” The following year, David and a friend rebuilt 60 lobster traps his father had supplied and became lobster fishermen, but it was with obvious reluctance that David did this.

His father, by this time, was more involved in using his schooner to move road construction equipment for the Goodyears than he was in fishing, yet he expected David to follow the old tradition. According to William Gough, David “talked his father into letting him use an old family store for a studio.” The Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador records that “During the winters of 1956-1959, he painted in a studio and set up in an old shop and then, during the summers, sold his work to visitors.” The author of the entry obviously didn’t realize that the “studio” and the “store” were the same building, a store being a place to store things rather than to sell them. Black Ice contains a reproduction of a photograph taken the year after “at school pond,” outside the makeshift studio. He is posed, seated on a rock with his hands hooked around his right knee. Gone are the leather jacket and jeans, and the artist is photographed instead in dress shoes, a white shirt, and sports jacket, ready to take on the Toronto art establishment.

This studio/store was the cause of a certain amount of friction. David would display a few of his paintings in the windows, and when one old man, who was the subject of a portrait, objected and sent his brother to destroy the painting, Gough writes that David met him sitting calmly in his studio with an empty sealing gun in his lap, and used it to threaten the angry man, who apparently was convinced the boy meant to shoot him with it.

David did receive a certain amount of encouragement from people in Wesleyville. The flowers on the dresser in Blackwood’s print of Aunt Gerti Hann (1987) are a rare early example of bright, varied colours in a Blackwood print. Aunt Gerti had given him a set of watercolours one Christmas when he was a child, just to see what he could do with them, and whenever she saw him, she told him never to stop painting. Blackwood claimed in an interview in the St. John’s Telegram that he was “drawing and painting in kindergarten” and was “encouraged all the way along,” though local gossip suggests that his father was the last person to encourage him.

In 1959, Blackwood was awarded a Newfoundland Centenary of Responsible Government Scholarship to study at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, thanks to the intervention of the newly elected and appointed Minister of Education, Dr. G. Alain Frecker. Without the scholarship, Blackwood would have been unable to study art, as his father was determined not to support his ambitions to become a professional artist. In fact, Jim Robbins, a teacher in the district, said that Edward Blackwood was so enraged by this turn of events that he deliberately burned down the store his son had been using as a studio. The small building was said to have been carved and painted all over the interior walls, and it was considered a valuable and fascinating artifact that would today be a beloved heritage building.

Myth and Legend is a beautiful and enlightening work, but it is clearly a companion piece to Black Ice, focusing on Blackwood and his art. Any collectors or admirers of the artist will want both if they do not already have the earlier volume. The text convinced this reader, at least, that there are still interesting things to learn about David Blackwood’s life and art that can be pieced together from both published and unpublished sources.

About the Reviewer

Robin McGrath was born in Newfoundland. She earned a doctorate from the University of Western Ontario, taught at the University of Alberta, and for 25 years did research in the Canadian Arctic on Inuit Literature and culture before returning home to Newfoundland and Labrador. She now lives in Harbour Main and is a full-time writer. Robin has published 26 books and over 700 articles, reviews, introductions, prefaces, teaching aids, essays, conference proceedings and chapbooks. Her most recent book is Labrador, A Reader’s Guide. (2023). She is a columnist for the Northeast Avalon Times and does freelance editing.

Book Details

Publisher: Goose Lane Editions and Art Gallery of Ontario

Publication date: 2025

Language: English

Print length: 143 pages

ISBN: 97817731104782 (hardcover)

Price $50.00

Just saw the exhibition at the AGO and Blackwood and would love to know more about him. This sounds good.

Thanks for the restack!