Duende and the Diaspora: Ben Meyerson's Seguiriyas

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Ben Meyerson’s debut poetry collection “Seguiriyas” opens with his shortest poem, “Close”:

Hours sound in me only as the chunter of rapids. Each day trails its tassels in my current and passes.

This compressed couplet highlights two senses of close – proximity and ending – which put in play an unending dialectic of sound and sense. “Close” bookends the collection with “Open,” the final poem of open-endedness that follows and reverses in flamenco’s strum and step. Between “to follow” and “to follow” the poem inserts a typographical marker […] where ellipses serve as stones or steps, and brackets incorporate boundaries of space and time. Currents and rapids fountain Meyerson’s verse, while stone tropes stabilize his architecture. Words brush one another in close choreography: assonance of hours and sound, me only; consonance of trails and tassels; and echoes of rapids … passes. Chunter is both chatter and chanter. The pentameter of each sentence is interrupted by line breaks to close each sentence and to make stanzas close to the poet who is both the only one and the one who hears only these sounds.

A “brush of tassels” reappears in the next poem, “Kol Nidre,” which again highlights close encounters in vows and vowels of the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur. Meyerson tassels the Hebrew prayer shawl (tallit) and flamenco’s emotive shawl as part of his diasporic drift across Ashkenaz and Sephardic heritages. The poet’s influences go well beyond these two sources, as multiple epigraphs create a diasporic intertextuality in resonance with his own verse. Czeslaw Milosz provides the first epigraph about a sponge, and Meyerson absorbs its suffering and saturation. Federico Garcia Lorca appears in the second epigraph about a cry that echoes among mountains. Meyerson borrows Lorca’s tassels in his own guitar strings: “Like the bow of a viola / the cry vibrates long strings / of wind.”

Lorca’s cry vibrates in Meyerson’s “Kol Nidre”: “Even rummaging through my insides to find the heavenly court / from where I stand on firm flagstones below the bimah.” Long i’s in the first line give way to sturdier alliterations in the second, from internal spirit to the body’s firmness in a siguiriya between court and bimah. This experience in the synagogue parallels his flamenco motion: “I sway in place, correct for turbulence, drone songs / to corral what has strayed: / an oath pitched into distance, / another year groping for return against the tide --.” Each phrase is a step held in place and pace by long a’s, hard consonance of “correct for turbulence,” a bounce and balance of correct and corral (with its choral undertone), and the pitch of strayed after sway and place. Lorca also drones “duende” – that elusive Spanish spirit that inspires, haunts, and subverts his verse. Moreover, duende derives from “owner of the house,” which contains its own uncanny or unheimlich spirit, for the house of verse is haunted by its million rooms and voices. Accordingly, the return against the tide is also a return of the repressed.

The return against the tide slides into the second stanza: “soil slides and sails beneath our feet. / We are always leaving, even when we stay.” From sibilance to long e’s the journey hovers between stillness and motion, stay and sway of duende, rooted temple and tempo below and beneath – flamenco’s pulsing undertow. The third stanza extends diaspora, as enjambment takes over from earlier end stops: “We jam our limbs into any shoal that seems / stable, clutch, ignore / the edges that threaten to cut or the strips that might dirty our hands.” M’s in the first line run into caesuras in the second – flamenco gestures wrapped in shoal or shawl. Watery imagery flows while stones arrest movement: “earth bucks us about as if a sea whose tug / would shuck our houses off their lots.” An undertow of short u’s saps the poet’s spirit, “wrench keys from their fitted locks / and scrub our towns from the maps.” These keys are carried into exile during the Spanish Inquisition when persecution and displacement erase a population of conversos longing for home but denied access. This unhomely duende recurs in “Para Tocar”: “First the Jews left the Madinat Garnata, / took the keys to their empty houses.” Lorca’s owner of the house is not at home.

The final stanza progresses from the particulars of family and community toward a grander abstraction of ocean and continent. “A brush of tassels along my wrist / from the tallit draped around my neighbor’s neck.” This relic of a bracelet about the bone reappears in the eponymous poem “Siguiriyas”: “like tefillin / squeezing an arm, seal this litter of / leather strap,” and “Our wrists are streaked by remnants.” The poet turns to his father’s halting hum and congregation’s chant, motions arrested in alliteration of “rags flung up to the rafters – rent.” Instead of the overwhelming downward trend he presents an upward direction, but only temporarily, for the earlier soil “beneath our feet” reappears as “a continent bent beneath / the ocean’s weight.” Rent and continent seek repair “toward their kin, whose faces they know / but can no longer trace” in the segue and duende of Kol Nidre. With no fixed icon or address, the diasporic poet follows seguiriyas along philosopher’s walk, becomes plural, and meanders the topography of displacement.

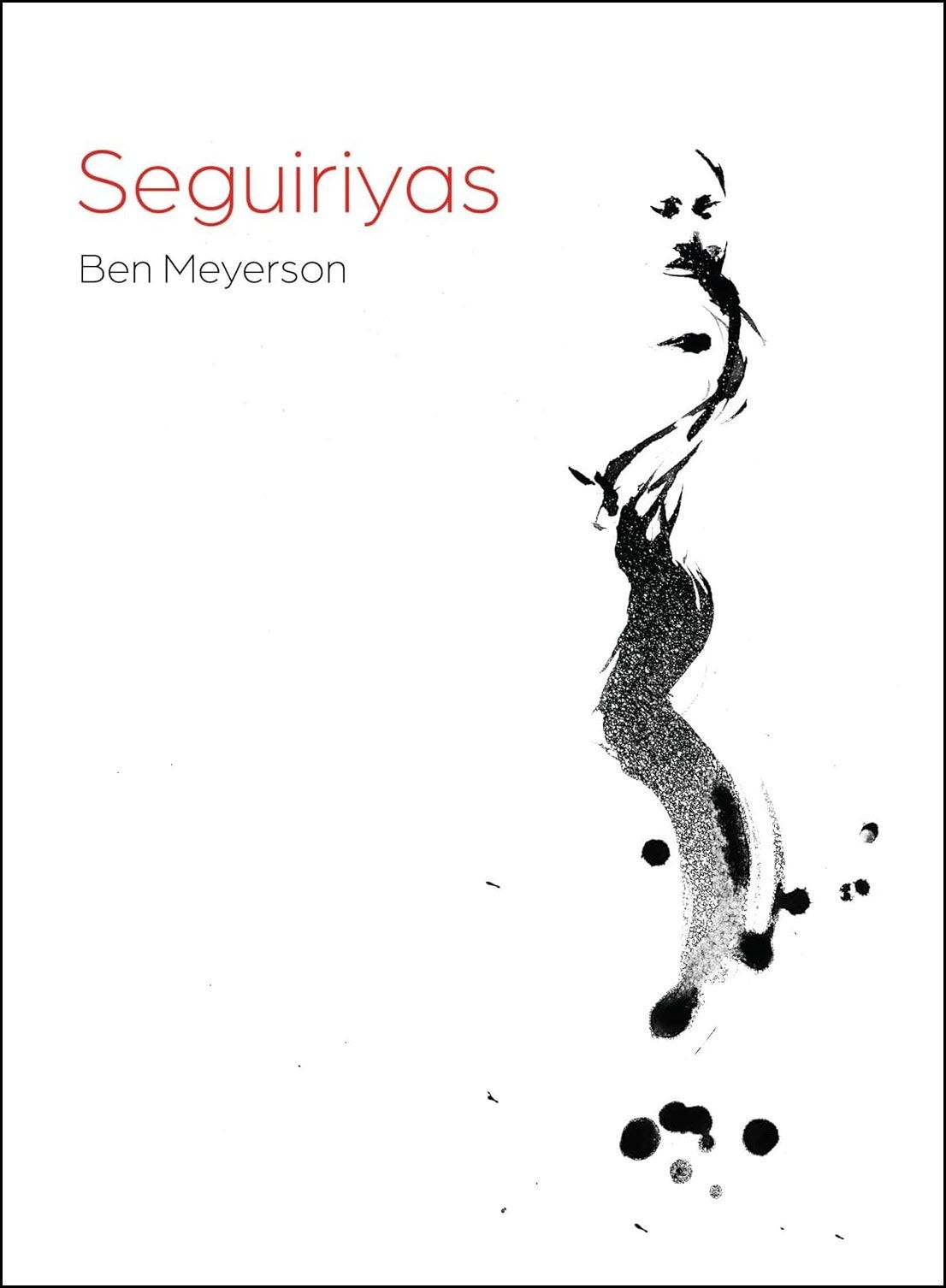

This trace of faces appears on the cover design of Seguiriyas where skin sheds its ink, blackens its blood, and silhouettes. A flamenco figure drips black from its face to the rest of its twirling body whose torso exhibits a fox-like curve that ends with black feet that trace and trance their motion.

Black drops underfoot serve as enigmatic ellipses of meandering meaning across dance floor and Diaspora. Flamenco dancer is a shapeshifter swirling stanzas throughout the volume; sidestepping or a knight’s move on a chessboard inform lines and stanzas:

Things move in place – forms pour into themselves.

He intones the Hebrew ingathering – “lekabets galuyoteinu.” As much as stones and water are dominant elements in his poetry, Meyerson also invokes a subtler flame within flamenco: “a vertical flame drawn around the wicks of our bodies” and “the fragrant drape of its smoke.” These shapes within “Daybreak Translation” continue: “our shapes are flung and pitched; our shadows lengthen and contract: the flickered movements.” Or he shapes gaps in “Two Months in Granada,” as palms keep rhythm, biting “into the hands that cut their tension, / no longer making the melody’s shape” and “then claiming the body as its question.” The figure on the cover contorts into a question mark and mask.

This subtler flame joins water and stone in “Al Cante” in the “burnt purr of a gullet liquefied by centuries” – conflagration of the Inquisition: “a rush of acrid heat from the stake / at which the punished body burns.” In “Granada After the Correlation” we watch “the faint burns / where air meets its skin.” In “Daybreak Translation” the “watch fires soften as night recedes”; a “combustion / of night” becomes “flame becomes world and so / can no longer be a flame.” “In Memory of Geoffrey Hill” concludes with a version of the burning bush garden: “tendrils of woodsmoke leap / from the chimneys along with the swept fumes / of history’s absolution, wafted up / from the clutter of its charred ingots.” To be followed by a coda of duende, departure, and its uncanny unheimlich etymology: “Always the strange, spiced musk of home. / Always a familiar voice in air to halt just before / the greeting. It is a terrible thing to leave.”

The departure of Jews and Muslims from Spain remains in the shapes and sounds of flamenco sculpting the surrounding emptiness of air – “the melismatic / tumble of the voice in the shadow just / shy of the candle’s lick.” Similarly, “After Convivencia” centuries from before 1492 to 1609 and after: “call the century back to its hearth in my chest / and chop it to kindling.” Heart and hearth fuse in the burning bush garden: “Dump its ash / into the flower beds that line / the trail in the garden where we walk together.” Meyerson’s stones, water, fire, and duende shape “Seguiriyas” “where ruins of old fires / meet a memory of sea.” From Iberia to Canada, he follows Jews and Gitanos in cadences of exile. A typo for the Hebrew prayer “Amidah” is the only blemish in this impressive book.

About the Author

Ben Meyerson is the author of four poetry chapbooks: In a Past Life, Holcocene, An Ecology of the Void, and Near Enough. He holds an MFA from the University of Minnesota and an MA in philosophy from the Universidad de Sevilla. He is currently a PhD candidate in comparative literature at the University of Toronto and splits his time between Canada and Spain. His poems, translations and essays have appeared in several journals, including Interim, PANK, Long Poem Magazine, El Mundo Obrero, Great River Review, The Inflectionist Review, Rust+Moth, and Pidgeonholes.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published extensively on Victorian, Canadian, and American Jewish literature.

He has published 250 essays and reviews in books and journals across Canada, the United States, and Europe.

Book Details

Publisher : Black Ocean

Publication date : Nov. 24 2023

Language : English

Print length : 96 pages

ISBN-10 : 1939568730

ISBN-13 : 978-1939568731

Thanks, Sheila.

The poet is lucky to have such a carefully attentive reader! Fascinating work.