Everyday Light by John Reibetanz

Reviewed by Michael Greenstein

Where Palimpsest Meets Pentimento

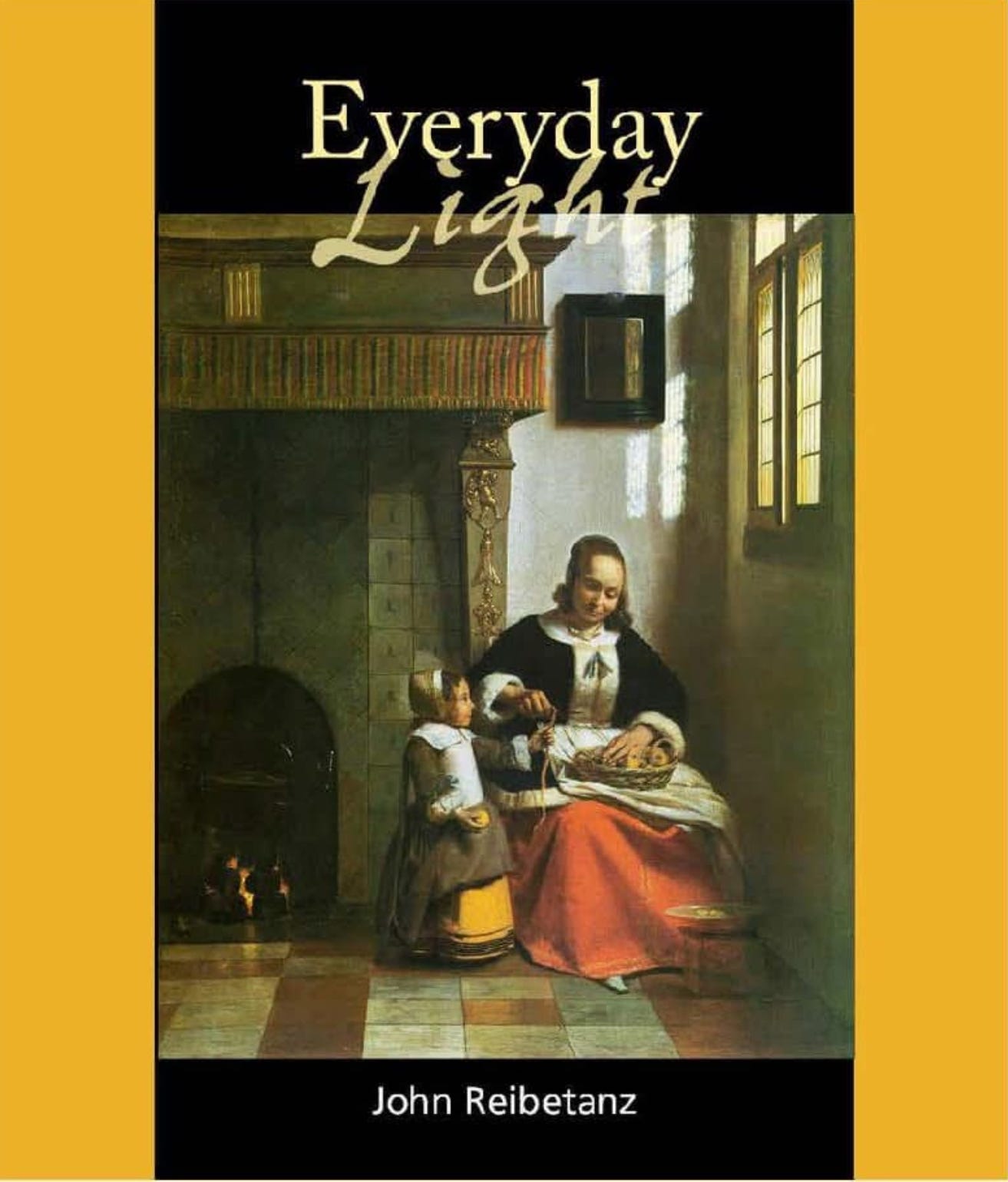

Every ekphrastic poem is a gained translation, a representation of a representation, a repainting of the original where lines meet lines, and colours mingle with sounds in synaesthetic shapes. Everyday Light, John Reibetanz’s eighteenth collection of poetry, uses the sonnet form to address Dutch painting of the 17th century. This form is tailored to meet the moment of these Dutch masters, but it also serves as a poignant framework for these scenes of domestic life framed by the artists themselves. Laura Cumming’s Thunderclap provides the epigraph to the “wildness and strangeness” in these paintings, poems, and conversations on canvas.

The cover of Everyday Light features Pieter de Hooch’s “A Woman Peeling Apples” (1663), which meets Reibetanz’s sonnet, “Peeled.” Verticality dominates de Hooch’s canvas from shaft of light entering the window to coloured stripes over the fireplace, and the dangling apple peel echoed in the fire in the arched hearth. The mother’s knife atop the peel is just above the child’s hand clutching the rind – a hand-me-down between generations. The woman’s white protruding shoe serves as a kind of footnote or afterthought to her ample red dress, as it choreographically toes the floor’s checkerboard tiles. The poet paints this scene in three quatrains and a concluding couplet.

The mother delights her child by peeling

an apple in that one long coil hanging

from between her thumb and the paring knife –

a rope the small girl grips and will play with.

Just as the daughter plays with the peel, so the poet plays with peal in his alliterative thunderclap, past peeled and progressive peeling, and oscillating rhythms of tetrameter and pentameter. Mother and daughter delight in everyday light and life. The dash at the end of the third line pares the stanza, connects coil to rope, as well as peeling, paring, and play.

Just as de Hooch plays with light and darkness, so Reibetanz thunderclaps the scene’s wildness and strangeness:

De Hooch plays too, peeling the afterlife

of layers of misogynistic myth

from his domestic scene. The skein of peel

is not the sloughed skin of a snake.

The umbilical cord between mother and daughter is the immediate afterlife of birthed connection (knife and afterlife, with and myth).

Negatives in the second half of the sonnet accompany Edenic sibilants, as the coil is not serpentine. The girl

whose right hand holds an apple, is no Eve.

The mirror hanging on the wall reflects

the window’s light rather than vanity,

and the fireplace’s kettle concocts

A drop to the hard k sound at the end of the third quatrain leads into the final witty couplet: “no witch’s brew: it’s applesauce, perhaps, / made with the woman’s myth-free peeled apples.” The paused “perhaps” gathers apples and wit, as the poet peels layers of meaning in de Hooch’s original light shed on tiles of floor and fireplace. Just as the brush licks the lambent surface, so the light licks the bowl and peel, while a plangent thunderclap penetrates the interior.

The poem that follows, “Linked,” is itself linked to the preceding “Peeled.” Based on de Hooch’s “A Woman Nursing an Infant with a Child and a Dog,” this sonnet begins with a sestet and ends with two quatrains:

Follow the light that enters through the high

window at right, then like benign lightning

angles floorwards, haloing mother’s cap,

caressing smiling child, bowl on her lap

from which she feeds the dog, and exiting

where kindred light flickers in the ingle.

In addition to end rhymes the stanza rhymes at beginning in follow-window, and midline light-right to trace light and sound effects. Long i’s alternating with short i’s sound the dramatic stillness in oxymoron (benign lightning) and stretched angles to ingle. Lambent light enters and exits the enjambed sentence to pause midline with precise caesuras.

The second stanza continues the muted thunderclap of lightning with “hallowed” echoing “haloing” in a dialectic between past and progressive present:

De Hooch also highlights the hallowed weave

threading mother and daughter by giving

the child a dress cut from the same fabric

as her mother’s star-swept morning-jacket.

Initial h’s pick up the “high” window in the first stanza, while the liquid l’s continue those dominant sounds from the title and first stanza to link lines and dress codes. The hyphenated line at the end of this stanza links cosmic and domestic sphere to keep nativity in “lower-case.” The final stanza carries the message home: “linked fingers holding the infant in place / beneath the mother’s breast are stained and chafed / like the diamond-shaped tiles beneath her feet.” Internal rhymes of “in” in the first line expand to long a’s in the second and e’s in the third to position bodies. De Hooch’s fingers are also stained, while the poet places the scene in lower-case and in the lineage of “Linked.”

The opening poem, “A New Hero,” is based on Johan de Brun’s Emblem X, “Cry, in distress.” The domestic hero is a husband defined by what he is “not” and contrasted with earlier heroes celebrated in epic poetry, as Reibetanz paints the tension between past and present participles:

He’s not dragging a fallen enemy

in the dust behind his wheeled chariot,

not holding up, in bragging victory,

a severed head, its dripping blood still hot.

In this history of heroics, plangency yields to lambency:

Helmetless, his own head sports a night-cap

as does the head of the infant nestled

on his left arm, as does his wife, asleep

on the bed behind them after nursing.

Parallelism of “as does” links family members and body parts to lead into the doze of “asleep.” Night-cap, nestled, and nursing prepare for nurture at the poem’s end:

In place of armour he dons a bathrobe

so pre-dawn chill won’t spoil his hushed songfest:

outpacing classic rivals, this hero

sings and soothes and walks the floor the longest

and stands before a hearth distant from Troy’s

ashes, to nurture rather than destroy.

Reibetanz’s rhyme scheme is one emblem, his play on dawn and knight another. Domestic sonnet replaces epic grandeur, nurture instead of armour, hushed songfest lulling an infant while subduing thunderclap. An eclipsed hero wears dailiness on his sleeve.

“No Water Nymph” approaches Gerrit Dou’s “Bathing Soldier” through negatives and alternating long and short o’s of forlorn melancholy: “The scene’s not mythological, although.” Denying mythological background, poet, painter, and soldier bathe in everyday light. His hunched back belongs more to a hushed bather than a soldier:

but even when you see the body’s male,

look for no Herculean torso, no

six-pack build, no rippling leg muscles –

no god, from stringy hair to swollen toes.

Body’s mail refers to the soldier’s armour. This new hero may be no hero, his torso a series of long o’s and toes swollen from battle, his trained orders turned to disorder. The bather’s gaze meets painter and poet in the final couplet: “looking and likely feeling forsaken, / no classic nude, this soldier stripped naked.” Ongoing bathing, looking, and feeling are undercut by “stripped.” Like de Hooch’s paring down the apple peel, Dou’s stripping gets to the core of character and silent survivor.

Several sonnets are split over two pages to allow for a study of form, which balances and unbalances with a thunderclap. “Conflicted” turns to Vermeer’s “Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window,” and opens with “Fears turn her room into a battlefield.” Epic dimensions enter the domestic scene: “Makeshift ramparts of drape, chair, and table / cannot prevent casualties.” A conflicted thunderclap resounds in this octave: “crumpled / top half of the letter she holds, fruit bowl / spilling still life onto the rucked carpet.” Tension builds in this octave’s details, as the girl’s face is mirrored in the window – a reminder of the various removes of witnessing, overseeing, and eavesdropping in pentimento and palimpsest. We have to flip the page for the concluding sestet which features Cupid trampling and dangling against her “warring” heart.

Similarly, “Grace” is split between two pages as it studies Vermeer’s “Woman Holding a Balance.” After two quatrains, the reader flips the page, just as the woman turns her back on apocalypse. Examining front and back, beginnings and endings, the poet weighs in on gravitas and lightness:

With a graceful equilibrium she lifts

in her right hand a set of scales to weigh

the light that glimmers on each balanced disk

in concert with the light she bears within,

cradling her head against the cowl that bears

the shadow of a human hand’s caress.

Vermeer rhymes the lights, and Reibetanz mirrors the disks.

Reibetanz’s balanced sonnets appear throughout the book. “Scape” centreson Gerard ter Borch’s equestrian equilibrium “balancing the wings of a brown tricorn / and balanced on the beast’s saddled brown flanks.” A “delicate balancing act” appears in the music making of “Prescient,” while “Poised” poses the question of man and woman writing a letter – “Will they lose their balance?” Likewise, “Held in Balance” zeroes in on Vermeer’s “The Concert,” as the poet balances painting and music, epiphany and thunderclap of “the first composer, breaking us of cares.”

Reibetanz uses “focus” to reinforce visual balance, but also as a reminder that focus derives from hearth and fireplace – hence the integration of home and family in these domestic settings. (Coincidentally, Cumming repeats home as a verb to focus on her subjects). Like Roland Barthes’ use of punctum in photography (a detail that pierces the viewer), Reibetanz’s gentle thunderclap introduces the “unhomely” within domestic calm. A synaesthetic impulse works through these paintings about music. In “Sightings” a young woman composer’s “eyes focus laser-like.” In “Kindred Spirit” the lacemaker has “complete focus on what her hands fashion.” In “Circles” “Our eyes focus on the gleaming white sphere” that is the eye’s equivalent. “17th Century Minimalist” portrays Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid”: “Now that he’s found his focus.” “Mind Has Mountains” scans ter Borch’s “Scene in an Inn”: “here focuses a microscopic lens.”

In his speaking pictures, the sonneteer balances and focuses on words that unlock mysteries of the Dutch Masters. Sounds of brushstrokes across stanzas find paintings’ punctum. His group show appears in “Main Show,” which underscores shadows in palimpsest and pentimento: “This work was published hearing many voices.” A polyphony of precursors “hid under many voices.” A thunderclap of colours and chorus circling:

the ingenious afterlife, spirited

away from its afterlife, down-dropped on

sweet-dreamed life, able to contemplate its

given life from another perspective.

Cadencing the canvas, Reibetanz says yes and no in gentler thunder as his reader follows a cicerone of seventeenth-century sonnets and portraits. “Sightings,” “Through the Looking Glass,” and “The Clowning Touch” circle “Conflicted,” “Poised,” “Peeled,” “Linked,” “Held in Balance,” “Mixed Attributes,” and “A Changed Prospect” to encompass the past.

Plaudits for Aeolus House’s fine design of these moments’ monuments.

About the Author

John Reibetanz is an award-winning poet and fellow of Victoria College, Toronto, and senior fellow at Massey College. His most recent collection is Metromorphoses.

About the Reviewer

Michael Greenstein is a retired professor of English (Université de Sherbrooke). He is the author of Third Solitudes: Tradition and Discontinuity in Jewish-Canadian Literature and has published widely on Victorian, Canadian, and American-Jewish literature.

Book Details

To order a copy of Everyday Light, email info@aeolushouse.com