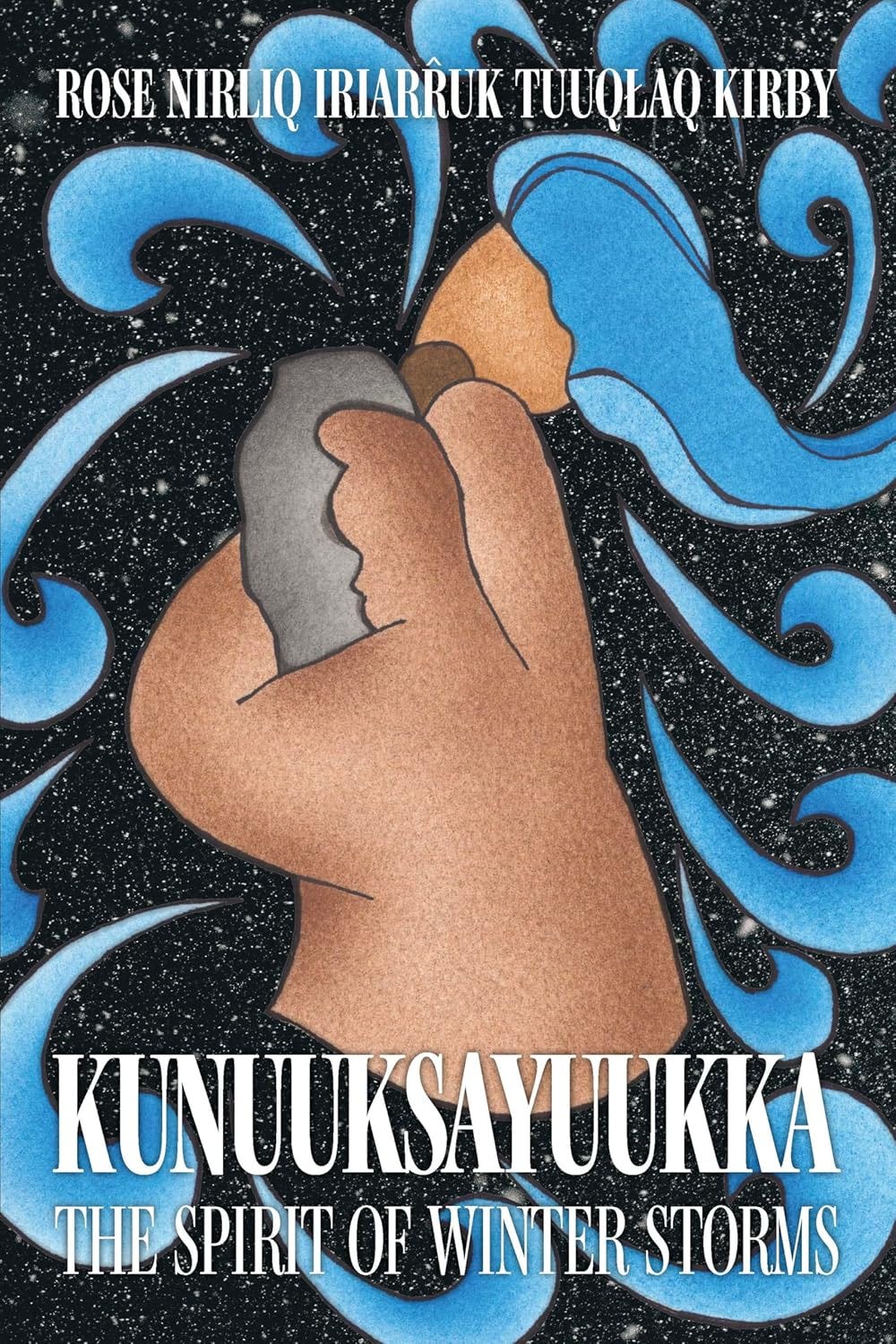

Kunuuksayuukka: The Spirit of Winter Storms by Rose Nirliq Iriarruk Tuuqlaq Kirby

Reviewed by Robin McGrath

Kunuuksayuukka, by Rose Kirby, is the most recent in a series of autobiographies by Canadian Inuit women, and it is consistent with the pattern established fairly early on of confining itself to what one Inuk called “the learning years.” It describes the author’s childhood but gives few details of her adult life. Of 783 works published by Inuit prior to 1981, more than a quarter were autobiographical. Two-thirds of those autobiographical works were by men who frequently based their structures on myths about Inuit heroes, while the women writers almost aways stopped describing their lives as soon as they reached maturity.1

“As the twentieth century developed, Inuit began to see literacy and publication as a way to assert themselves politically.”

From the late 19th century, Inuit of both genders were encouraged by Christian missionaries and anthropologists to document their lives as a way of conveying information about their cuture and maintaining literacy that contributed to religious practice. As the 20th century progressed, Inuit began to see literacy and publication as a way to assert themselves politically.

Kirby, now an Inuvialuktun Language specialist with the western Arctic education system, was sent to residential school in Aklavik as a small child, and was there for three miserable years during which time she lost her mother tongue. Unlike many Indigenous residential school survivors, she apparently did not suffer the sexual abuse or other brutalities reported by many students, but she certainly suffered from the loss of her language, which was banned at the school, and the separation from her parents and grandparents. Corporal punishment and humiliation at the hands of the nuns were no worse than what any child in a Roman Catholic school system experienced at that time. However, once returned to her parents, Kirby needed many years to recover her language and culture. This book successfully recaptures the rich tradition she strove to hold onto as she grew up.

During Kirby’s childhood, her family moved around seasonally, according to where fish and game were available, but they were generally in the area of Paulatuuq. Her father, who had attended residential school for many years, spoke fluent English but as an adult needed to acquire hunting and survival skills from his older relatives. He seems to have adapted successfully to this lifestyle, but did occasionally work for non-Inuit as a guide and general labourer.

Kirby’s recollections of her childhood are fairly detailed — what food they ate, how she learned to prepare skins for sewing, who her playmates were, what games they played — but it is not overly repetitive. She describes how she used stones as toys, standing in for dolls when tucked down the back of her parkas, and serving as a variety of other fantasy objects. Other than an occasional fright from a grizzly or a close call in a boat, there are no heart-stopping events in Kirby’s early years, but her repeated accounts of a nomadic life unfold in a leisurely, pleasing way.

Occasionally Kirby tells a brief story garnered from her elders or made up by herself or one of her siblings. She clearly loved and was loved by her family, and was nourished by her relationships with the elders she encountered.

In the 1940s, when Kirby was born, the Arctic was perceived by most southerners as a bleak, harsh, freezing wasteland entirely without comfort or redeeming merit. The food available to the people who lived there was viewed as uncivilized and unappetizing, and probably unhealthy. Residential school, as imagined by southern missionaries and government agents, probably appeared to be a desirable haven for Indigenous children — real beds, heated housing, three meals a day, and cloth rather than skin clothing. The reality, of course was far different.

Kirby’s descriptions of the landscape give the lie to the stereotype of the Arctic landscape being a wasteland. For example, when she travels on foot with her family over McKentyre Hill, she comments -“It was a beautiful sight when we got to the top...awesome as far as the eye could see — Imnaarut (hills and eskers), Tasiryuk Lake, Pinguqsaaryuk (pingo), Qimialuk, Paulatuu, and towards Langton Bay. This was and still is my world.”

“Seen through the eyes of a child raised in that environment and culture, the Arctic provides a feast for the eyes and the tongue.”

Even as a child, Kirby takes an intense interest in the preparation and preservation of the dozens of animals her parents provide, anticipating the pleasure that awaits her when the time comes to consume everything from swans to green, leafy mountain sorrel. Seen through the eyes of a child raised in that environment and culture, the Arctic provides a feast for the eyes and the tongue.

Kirby’s reminiscences bring her up to about age 17, when she is given the option of upgrading her Grade Two education. The brief biography on the back cover informs readers that Kirby had a long career as an educator, and that she married and had a family, but how she managed this and what impediments she had to overcome to accomplish this are a blank. The last fifty pages of this 300-page book concern not Kirby’s life but what she calls her “Legacies,” the things she learned from her elders and relatives.

The book is an easy, informative read, but it is not without its problems. From the first page of the Introduction, Kirby adopts a practice of providing both the English and the Inuvialuktun words for common nouns. She doesn’t explain her motivation for doing this, although it is almost certainly intended to remind non-Inuit readers that the culture she is remembering was not English. If so, the point seems to be overdone.

In the course of two pages, where she is describing setting up a fish camp with her family, she repeatedly refers to the tent they will be living in variously as a “tupiq (tent),” a “tupiq,” a “tupiq (tent),” a “tupiq,” a “tent,” a “tupiq (tent), a “tupiq tent” and a “tent.” For someone trying to learn the language, such repetition might be helpful, but for a reader who either already knows what a “tupiq” is, or who is less interested in what a tent is called than in what is occurring in it, this quickly becomes overly-repetitious, an impediment to the flow of the story.

Readers are reminded 100 times or more that tea, which is a very common drink in Inuit communities, is “tii” in the local dialect. Such repitition is exhausting and probably counterproductive in the long run. Kirby repeats this bilingual naming of objects and animals all through her text, also applying the practice every time she introduces a character by giving their adopted English names as well as the various Inuvialuktun spellings of their birth names.

Readers familiar with the Central or Eastern Arctic will recognize many of the common cultural pastimes Kirby describes, such as groups of children visiting dwellings simply to sit, observe, and listen, or the practice of shaking hands with everybody in a group, including babies and close relatives. You have to read to page 238 before anyone gets a spontaneous hug.

The ever-present danger of grizzly bears out on the land in this account is not something that is common elsewhere in the Arctic (this reviewer had 13 grizzlies pass through a camp near Shingle Point in one afternoon) and polar bears occasionally do show up.

Inuinaktung people in those days heated their tents with willow or local coal rather than seal oil, an impossibility elswhere in Nunavut.

In some cases, a few explanations might have been helpful. The DEW line is so common up north that it might seem redundant to explain that these were Distant Early Warning stations, there to serve as an alert in the Cold War. The Smoking Hills near Paulatuk are not temporary aberrations or wildfires — they are the spontaneous combustion of sulphur-rich lignite and shale deposits within the hills that have burned for centuries. A few words regarding the history of the Oblate missionaries might also have been helpful. However, this is not a book of general history or political development — Rather, it is a memoir of a unique childhood, and a very good one.

Hopefuly, Rose Kirby is intending to break the pattern of Inuit women not drawing attention to their mature years in their biographies, and is at this very moment working on the next volume about her life.

About the Author

Rose Marie Iriarr̂uk Nirliq Tuuqłak Kirby (née Thrasher) was born at the Hornaday River in 1946, during a time when Inuvialuit lived nomadically. She spent her early years travelling with family around the Paulatuuq area following the changing seasons. In 1968, Rose finally found a religion that embraced her Inuvialuit culture and values. She was the first Inuk woman to become a Bahá’í, leading her to her Bahá’í husband Tom Kirby. Rose had a long career as an educator in Fort McPherson, Aktlarvik, Inuuvik, and Paulatuuq, then as an Inuvialuktun Language Specialist for her local education board. She has devoted her life to educating others about her Inuvialuit culture, history, and language. Today, Rose lives in Inuuvik, Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR), with her daughter Cheryl and granddaughters Brianna and Aubri (and their two chihuahuas, Daisy and Mocha).

About the Reviewer

Robin McGrath was born in Newfoundland. She earned a doctorate from the University of Western Ontario, taught at the University of Alberta, and for 25 years did research in the Canadian Arctic on Inuit Literature and culture before returning home to Newfoundland and Labrador. She now lives in Harbour Main and is a full-time writer. Robin has published 26 books and over 700 articles, reviews, introductions, prefaces, teaching aids, essays, conference proceedings and chapbooks. Her most recent book is Labrador, A Reader’s Guide. (2023). She is a columnist for the Northeast Avalon Times and does freelance editing.

Book Details

Publisher: Inuvialuit Communications Society

Publication date: 2024

Print length: 299 pages

ISBN: 978-0-9812627-1-0

See McGrath, Robin. “Circumventing the Taboos: Inuit Women’s Autobiographies.” Papers From the Seventh Inuit Studies Conference, l9-23 August, Fairbanks, Alaska. Quebec, P.Q.: Association Inuksiutiit Katimajiit, l992, 215-225. Rpt. in Undisciplined Women, ed. Pauline Greenhill and Diane Tye. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997, pp. 222-232.